Arabella pulled her hands resolutely away, and turned from him to hide her quivering lips, and suffused eyes. “It is worse than you know!” she said, in a stifled tone. “When you know all the truth, you will not wish to marry me! I have been worse than untruthful: I have been shameless! I can never marry you, Mr. Beaumaris!”

“This is most disturbing,” he said. “Not only have I sent the notice of our betrothal to the Gazette, and the Morning Post, but I have obtained your father’s consent to our marriage.”

At this, she spun round to face him again, a look of utter astonishment in her face. “My father’s consent?” she repeated incredulously.

“It is usual, you know,” explained Mr. Beaumaris apologetically.

“But you do not know my father!”

“On the contrary. I made his acquaintance last week, and spent two most agreeable nights at Heythram,” he said.

“But—Did Lady Bridlington tell you?”

“No, not Lady Bridlington. Your brother let slip the name of his home once, and I have an excellent memory. I am sorry, by the way, that Bertram should have been having such an uncomfortable time during my absence from town. That was quite my fault: I should have sought him out, and settled his difficulties before I left for Yorkshire. I did write to him, but he had unfortunately departed from the Red Lion before the delivery of my letter. However, you won’t find that the experience has harmed him, so I must hope to be forgiven.”

Her cheeks were now very much flushed. “You know it all then! Oh, what must you think of me? I asked you to marry me because—because I wanted you to give me seven hundred pounds to save poor Bertram from a debtor’s prison!”

“I know you did,” said Mr. Beaumaris cordially. “I don’t know how I contrived to keep my countenance. When did it occur to you, my ridiculous little love, that to demand a large sum of money from your bridegroom as soon as the ring was on your finger might be a trifle awkward?”

“Just now—in your chaise!” she confessed, covering her face with her hands. “I couldn’t do it! I have behaved very, very badly, but when I realized what I was about—oh, indeed, I knew I could never do it!”

“We have both behaved very badly,” he agreed. “I encouraged Fleetwood to spread the news that you were a great heiress: I even allowed him to suppose that I knew all about your family. I thought it would be amusing to see whether I could make you the rage of London—and I blush to confess it, my darling: it was amusing! Nor do I really regret it in the least, for if I had not set out on this most reprehensible course we might never have come much in one another’s way again, after our first meeting, and I might never have discovered that I had found the very girl I had been looking for for so long.”

“No, no, how can you say so?” she exclaimed, large tears standing on the ends of her lashes. “I came to London in the hope of—of contracting an eligible marriage, and I asked you to, marry me because you are so very rich! You could not wish to marry such an odious creature!”

“No, perhaps I couldn’t,” he replied. “But although you may have forgotten that when I first addressed myself to you, you declined my offer, I have not If wealth was all your object, I can’t conceive what should have induced you to do so! It seemed to me that you were not entirely indifferent to me. All things considered, I decided that my proper course was to present myself to your parents without further loss of time. And I am very glad I did so, for not only did I spend a very pleasant time at the Vicarage, but I also enjoyed a long talk with your mother—By the way, do you know how much you resemble her? more, I think, than any of your brothers and sisters, though they are all remarkably handsome. But, as I say, I enjoyed a long talk with her, and was encouraged to hope, from what she told me, that I had not been mistaken in thinking you were not indifferent to me.”

“I never wrote a word to Mama, or even to Sophy, about—about—not being indifferent to you!” Arabella said involuntarily.

“Well, I do not know how that may be,” said Mr. Beaumaris, “but Mama and Sophy were not at all surprised to receive a visit from me. Perhaps you may have mentioned me rather frequently in your—letters, or perhaps Lady Bridlington gave Mama a hint that I was the most determined of your suitors.”

The mention of her godmother made Arabella start, and exclaim: “Lady Bridlington! Good God, I left a letter for her on the table in the hall, telling her of the dreadful thing I had done, and begging her to forgive me!”

“Don’t disturb yourself, my love: Lady Bridlington knows very well where you are. Indeed, I found her most helpful, particularly when it came to packing what you would need for a brief sojourn at my grandmother’s house. She promised that her own maid should attend to the matter while we were listening to that tedious concert. I daresay she has long since told that son of hers that he may look for the notice of our engagement in tomorrow’s Gazette, together with the intelligence that we have both of us gone out of town to stay with the Dowager Duchess of Wigan. By the time we reappear in London, we must hope that our various acquaintances will have grown so accustomed to the news that we shall not be quite overwhelmed by their astonishment, their chagrin, or their felicitations. But I am strongly of the opinion that you should permit me to escort you home to Heythram as soon as possible: you will naturally wish your father to marry us, and I am extremely impatient to carry off my wife without any loss of time. My darling, what in the world have I said to make you cry?”

“Oh, nothing, nothing!” sobbed Arabella. “Only that I don’t deserve to be so happy, and I n-never was indifferent to you, though I t-tried very hard to be, when I thought you were only trifling with m-me!”

Mr. Beaumaris then took her firmly into his arms, and kissed her; after which she derived much comfort from clutching the lapel of his elegant coat, and weeping into his shoulder. None of the very gratifying things which Mr. Beaumaris murmured into the curls that were tickling his chin had any other effect on her than to make her sob more bitterly than ever, so he presently told her that even his love for her could not prevail upon him to allow her to ruin his favourite coat. This changed her tears to laughter, and after he had dried her face, and kissed her again, she became tolerably composed, and was able to sit down on the sofa beside him, and to accept from him the glass of tepid milk which he told her she must drink if she did not wish to incur Mrs. Watchet’s displeasure. She smiled mistily, and sipped the milk, saying after a moment: “And Papa gave his consent! Oh, what will he say when he knows the whole? What did you tell him?”

“I told him the truth,” replied Mr. Beaumaris.

Arabella nearly dropped the glass. “All the truth?” she faltered, dismay in her face.

“All of it—oh, not the truth about Bertram! His name did not enter into our conversation, and I strictly charged him, when I sent him off to Yorkshire, not to divulge one word of his adventures. Much as I like and esteem your father, I cannot feel that any good purpose would be served by distressing him with that story. I told him the truth about you and me.”

“Was he—dreadfully displeased with me?” asked Arabella, In a small, apprehensive voice.

“He was, I fear, a little grieved,” owned Mr. Beaumaris. “But when he understood that you would never have announced yourself to have been an heiress had you not overheard me talking like a coxcomb to Charles Fleetwood, he was soon brought to perceive that I was even more to blame for the deception than you.”

“Was he,” said Arabella doubtfully.

“Drink your milk, my love! Certainly he was. Between us, your Mama and I were able to show him that without my prompting Charles would never have spread the rumour abroad, and that once the rumour had been so spread it was impossible for you to deny it, since naturally no one ever asked you if it were true. I daresay he may give you a little scold, but I am quite sure you are already forgiven.”

“Did he forgive you too?” asked Arabella, awed.

“I had all the merit of making the confession,” Mr. Beaumaris pointed out virtuously. “He forgave me freely. I cannot imagine why you should look so much surprised: I found him in every way delightful, and have seldom enjoyed an evening more than the one I spent conversing with him in his study, after your Mama and Sophy had gone to bed. Indeed, we sat talking until the candles guttered in their sockets.”

Arabella’s awed expression became even more marked. “Dear sir, what—what did you talk about?” she enquired quite unable to visualize Papa and the Nonpareil hobnobbing together.

“We discussed certain aspects of Wolfs Prolegomena ad Homerum, a copy of which work I chanced to see upon his bookshelf,” replied Mr. Beaumaris calmly. “I myself picked up a copy when I was in Vienna last year, and was much interested in Wolf’s theory that more than one hand was employed in the writing of the Iliad and the Odyssey.”

“Is—is that what the book is about?” asked Arabella.

He smiled, but replied gravely: “Yes, that is what it is about—though your father, a far more profound scholar than I am, found the opening chapter, which treats of the proper methods to be used in the recension of ancient manuscripts, of even more interest. He took me a little out of my depth there, but I hope I may have profited by his very just observations.”

“Did you enjoy that?” demanded Arabella, much impressed.

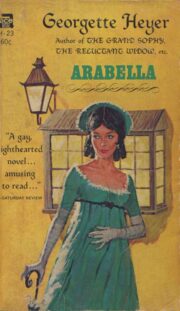

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.