Ulysses wagged his tail. He was not only willing to do Mr. Beaumaris justice, but presently indicated his readiness to accompany him on whatever expedition he had in mind.

“It would be useless to suggest, I suppose, that you are occupying Clayton’s seat?” said Mr. Beaumaris, mounting into his tilbury.

Clayton, grinning, expressed himself as being agreeable to taking the little dog on his knee, but Mr. Beaumaris shook his head.

“No, I fear he would not like it. I shan’t need you,” he said, and drove off, remarking to his alert companion: “We are now faced with the wearing task of tracing down that foolish young man’s inarticulate friend, Felix Scunthorpe. I wonder whether, in the general medley, there is any bloodhound strain in you?”

He drew blank at Mr. Scunthorpe’s lodging, but on being informed that Mr. Scunthorpe had mentioned that he was going to Boodle’s, drove at once to St. James’s Street, and was so fortunate as to catch sight of his quarry, walking up the flagway: He reined in, and called imperatively: “Scunthorpe!”

Mr. Scunthorpe had naturally perceived who was driving a spanking chestnut between the shafts of the tilbury, but as he had no expectation of being recognized by the Nonpareil this summons surprised him very much. He was even a little doubtful, and said cautiously: “Me, sir?”

“Yes, you. Where is young Tallant?” He saw an expression of great wariness descend upon Mr. Scunthorpe’s face, and added impatiently: “Come, don’t be more of a fool than you can help! You don’t suppose I am going to hand him over to the tipstaffs, do you?”

“Well, he’s at the Cock,” disclosed Mr. Scunthorpe reluctantly. “That is to say,” he corrected himself, suddenly recalling his friend’s incognito, “he is, if you mean Mr. Anstey.”

“Have you any brothers?” demanded Mr. Beaumaris.

“No,” said Mr. Scunthorpe, blinking at him. “Only child.”

“You relieve my mind. Offer my congratulations to your parents!”

Mr. Scunthorpe thought this over, with knit brow, but could make nothing of it. He put Mr. Beaumaris right on one point “Only one parent,” he said. “Father died three months after I was born.”

“Very understandable,” said Mr. Beaumaris. “I am astonished that he lingered on for so long. Where is this Cock you speak of?”

“Thing is—not sure I ought to tell you!” said Mr. Scunthorpe.

“Take my word for it, you will be doing your misguided friend an extremely ill-turn if you don’t tell me!”

“Well, it’s at the corner of Duck Lane, Tothill Fields,” confided Mr. Scunthorpe, capitulating.

“Good God!” said Mr. Beaumaris, and drove off.

The Cock inn, however, though a small, squat building, proved to be more respectable than its situation had led Mr. Beaumaris to suppose. Duck Lane might abound in filth of every description, left to rot in the road, but the Cock seemed to be moderately clean, and well-kept. It even boasted an ostler, who emerged from the stable to gape at the tilbury. When he understood that the swell handling the ribbons had not merely stopped to enquire the way, but really did desire him to take charge of his horse and carriage, a vision of enormous largesse danced before his eyes, and he hastened to assure this noble client that he was ready to bestow his undivided attention on the equipage.

Mr. Beaumaris then descended from the tilbury, and walked into the tap of the inn, where his appearance caused a waterman, a jarvey off duty, two bricklayer’s labourers, a scavenger, and the landlord to break off their conversation in mid-sentence to stare at him.

“Good-morning!” said Mr. Beaumaris. “You have a Mr. Anstey putting up here, I think?”

The landlord, recovering from his surprise, came forward, bowing several times. “Yes, your honour! Oh, yes, indeed, your honour!—Chase that cur out of here, Joe!—If your honour will—”

“Do nothing of the sort, Joe!” interrupted Mr. Beaumaris.

“Is he yours, sir?” gasped the landlord.

“Certainly he is mine. A rare specimen: his family tree would surprise you! Is Mr. Anstey in?”

“He’ll be up in his room, sir. Keeps hisself to hisself, in a manner of speaking. If your honour would care to step into the parlour, I’ll run up and fetch him down before the cat can lick her ear.”

“No, take me up to him,” said Mr. Beaumaris. “Ulysses, do stop hunting for rats! We have no time to waste on sport this morning! Come to heel!”

Ulysses, who had found a promising hole in one corner of the tap, and was snuffing at it in a manner calculated to keep its occupant cowering inside it for the next twenty-four hours at least, regretfully obeyed this command, and followed Mr. Beaumaris up a steep, narrow stairway. The landlord scratched on one of the three doors at the top of this stair, a voice bade him come in, and Mr. Beaumaris, nodding dismissal to his guide, walked in, shut the door behind him, and said cheerfully: “How do you do? I hope you don’t object to my dog?”

Bertram, who had been sitting at a small table, trying for the hundredth time to hit upon some method of solving his difficulties, jerked up his head, and sprang to his feet, as white as his shirt. “Sir!” he uttered, grasping the back of his chair with one shaking hand.

Ulysses, misliking his tone, growled at him, but was called to order. “How many more times am I to speak to you about your total lack of polish, Ulysses?” said Mr. Beaumaris severely. “Never try to pick a quarrel with a man under his own roof! Lie down at once!” He drew off his gloves, and tossed them on to the bed. “What a very tiresome young man you are!” he told Bertram amiably.

Bertram, his face now as red as a beetroot, said in a choked voice: “I was coming to your house on Thursday, as you bade me!”

“I’m sure you were. But if you hadn’t been so foolish as to leave the Red Lion so—er—hurriedly, there would not have been the slightest need for this rustication of yours. You would not have worried yourself half-way to Bedlam, and I should not have been obliged to bring Ulysses to a locality you can see he does not care for.”

Bertram glanced in a bewildered way towards Ulysses, who was sitting suggestively by the door, and said: “You don’t understand, sir. I—I was rolled-up! It was that, or—or prison, I suppose!”

“Yes, I rather thought you were,” agreed Mr. Beaumaris. “I sent a hundred pound banknote to you the next morning, together with my assurance that I had no intention of claiming from you the vast sums you lost to me. Of course, I should have done very much better to have told you so at the time—and better still to have ordered you out of the Nonesuch at the outset! But you will agree that the situation was a trifle awkward.”

“Mr. Beaumaris,” said Bertram, with considerable difficulty, “I c-can’t redeem my vowels now, but I pledge you my word that I will redeem them! I was coming to see you on Thursday, to tell you the whole, and—and to beg your indulgence!”

“Very improper,” approved Mr. Beaumaris. “But it is not my practice to win large sums of money from schoolboys, and you cannot expect me to change my habits only to accommodate your conscience, you know. Shall we sit down, or don’t you trust the chairs here?”

“Oh, I beg pardon!” Bertram stammered, flushing vividly. “Of course! I don’t know what I was thinking about! Pray, will you take this chair, sir? But it will not do! I must and I will—Oh, can I offer you any refreshment? They haven’t anything much here, except beer and porter, and gin, but if you would care for some gin—”

“Certainly not, and if that is how you have been spending your time since last I saw you I am not surprised that you are looking burned to the socket.”

“I haven’t been—at least, I did at first, only it was brandy—but not—not lately,” Bertram muttered, very shamefaced.

“If you drank the brandy sold in this district, you must have a constitution of iron to be still alive,” remarked Mr. Beaumaris. “What’s the sum total of your debts? Or don’t you know?”

“Yes, but—You are not going to pay my debts, sir!” A dreadful thought occurred to him; he stared very hard at his visitor, and demanded: “Who told you where I was?”

“Your amiable but cork-brained friend, of course.”

“Scunthorpe?” Bertram said incredulously. “It was not—it was not someone else?”

“No, it was not someone else. I have not so far discussed the matter with your sister, if that is what you mean.”

“How do you know she is my sister?” Bertram said, staring at him harder than ever. “Do you say that Scunthorpe told you that too?”

“No, I guessed it from the start. Have you kept your bills? Let me have them!”

“Nothing would induce me to!” cried Bertram hotly. “I mean, I am very much obliged to you, sir, and it’s curst good of you, but you must see that I couldn’t accept such generosity! Why, we are almost strangers! I cannot conceive why you should think of doing such a thing for me!”

“Ah, but we are not destined to remain strangers!” explained Mr. Beaumaris, “I am going to marry your sister.”

“Going to marry Bella?” Bertram said.

“Certainly. You perceive that that puts the whole matter on quite a different footing. You can hardly expect me either to win money from my wife’s brother at faro, or to bear the odium of having a relative in the Fleet. You really must consider my position a little, my dear boy.”

Bertram’s lip quivered. “I see what it is! She did go to you, and that is why—But if you think, sir, that I have sunk so low I would let Bella sacrifice herself only to save me from disgrace—”

Ulysses, taking instant exception to the raised voice, sprang to Mr. Beaumaris’s side, and barked a challenge at Bertram. Mr. Beaumaris dropped a hand on his head. “Yes, very rude, Ulysses,” he agreed. “But never mind! Bear in mind that it is not everyone who holds me in such high esteem as you do!”

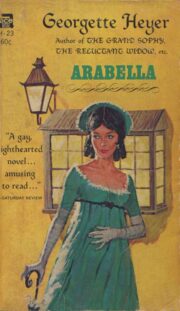

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.