Leaving his valet to repair the damage to his wardrobe, and his faithful admirer to sleep off the effects of a Gargantuan meal, Mr. Beaumaris left the house, and walked to Park Street. Here he was met by the intelligence that my lord, my lady, and Miss Tallant had gone out in the barouche to the British Museum, where Lord Elgin’s much disputed marbles were now being exhibited, in a wooden shed built for their accommodation. Mr. Beaumaris thanked the butler for this information, called up a passing hackney, and directed the jarvey to drive him to Great Russell Street.

He found Miss Tallant, her disinterested gaze fixed upon a sculptured slab from the Temple of Nike Apteros, enduring a lecture from Lord Bridlington, quite in his element. It was Lady Bridlington who first perceived his tall, graceful figure advancing across the saloon, for since she had naturally seen the collection of antiquities when it was on view at Lord Elgin’s residence in Park Lane, and again when it was removed to Burlington House, she felt herself to be under no obligation to look at it a third time, and was more profitably engaged in keeping a weather eye cocked for any of her acquaintances who might have elected to visit the British Museum that morning. Upon perceiving Mr. Beaumaris, she exclaimed in accents of delight: “Mr. Beaumaris! What a lucky chance, to be sure! How do you do? How came you not to be at the Kirkmichael’s Venetian Breakfast yesterday? Such a charming party! I am persuaded you must have enjoyed it! Six hundred guests—only fancy!”

“Amongst so many, ma’am, I am flattered to know that you remarked my absence,” responded Mr. Beaumaris, shaking hands. “I have been out of town for some days, and only returned this morning. Miss Tallant! ’Servant, Bridlington!”

Arabella, who had started violently upon hearing his name uttered, and quickly turned her head, took his hand in a clasp which seemed to him slightly convulsive, and raised a pair of strained, enquiring eyes to his face. He smiled reassuringly down into them, and bent a courteous ear to Lady Bridlington, who was making haste to assure him that she had come to the Museum merely to show the Grecian treasures to Arabella, who had not been privileged to see them on their first showing. Lord Bridlington, not averse from any aggrandizement to his audience, began in his consequential way to expound his views on the probable artistic value of the fragments, a recreation which would no doubt have occupied him for a considerable period of time had Mr. Beaumaris not cut him short by saying, in his most languid way: “The pronouncements of West, and of Sir Thomas Lawrence, must, I imagine, have established the aesthetic worth of these antiquities. As to the propriety of their acquisition, we may, each one of us, hold to our own opinion.”

“Mr. Beaumaris, do you care to visit Somerset House with us?” interrupted Lady Bridlington. “I do not know how it comes about that we were not there upon Opening Day, but such a rush of engagements have we been swept up in—that I am sure it is a wonder we have time to turn round! Arabella, my love, I daresay you are quite tired of staring at all these sadly damaged bits of frieze, or whatever it may be called—not but what I declare I could feast my eyes on it for ever!—and will be glad to look at pictures for a change!”

Arabella assented to it, throwing so beseeching a look at Mr. Beaumaris that he was induced to accept a seat in the barouche.

During the drive to the Strand, Lady Bridlington was too much occupied in catching the eyes of chance acquaintances, and drawing their attention to the distinguished occupant of one of the back seats by bowing and waving to them, to have much time for conversation. Arabella sat with her eyes downcast, and her hand fidgeting with the ribands tied round the handle of her sunshade; and Mr. Beaumaris was content to watch her, taking due note of her pallor, and the dark shadows beneath her eyes. It was left to Lord Bridlington to entertain the company, which he did very willingly, prosing uninterruptedly until the carriage turned into the courtyard of Somerset House.

Once inside the building, Lady Bridlington, whose ambitions had for some time been centered on promoting a match between Arabella and the Nonpareil, seized the first opportunity that offered of drawing Frederick away from the interesting pair. She stated her fervent desire to see the latest example of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s art, and dragged him away from a minute inspection of the President’s latest enormous canvas to search for this fashionable masterpiece.

“In what way can I serve you, Miss Tallant?” said Mr. Beaumaris quietly.

“You—you had my letter?” faltered Arabella, glancing fleetingly up into his face.

“This morning. I went instantly to Park Street, and, apprehending that the matter was of some urgency, followed you to Bloomsbury.”

“How kind—how very kind you are!” uttered Arabella, in accents which could scarcely have been more mournful had she discovered him to have been a monster of cruelty.

“What is it, Miss Tallant?”

Bearing all the appearance of one rapt in admiration of the canvas before her, she said: “I daresay you may have forgot all about it, sir, but—but you told me once—that is, you were so obliging as to say—that if my sentiments underwent a change—”

Mr. Beaumaris mercifully intervened to put an end to her embarrassment. “I have certainly not forgotten it,” he said. “I perceive Lady Charnwood to be approaching, so let us move on! Am I to understand, ma’am, that your sentiments have undergone a change?”

Miss Tallant, obediently walking on to stare at one of the new Associates’ Probationary Pictures (described in her catalogue as “An Old Man soliciting a Mother for Her Daughter who was shewn unwilling to consent to so disproportionate a match”) said baldly: “Yes.”

“My surroundings,” said Mr. Beaumaris, “make it impossible for me to do more than assure you that you have made me the happiest man in England, ma’am.”

“Thank you,” said Arabella, in a stifled tone. “I shall try to be a—to be a comfortable wife, sir!”

Mr. Beaumaris’s lips twitched, but he replied with perfect gravity: “For my part, I shall try to be an unexceptionable husband, ma’am!”

“Oh, yes, I am sure you will be!” said Arabella naively. “If only—”

“If only—?” prompted Mr. Beaumaris, as she broke off.

“Nothing!” she said hastily. “Oh, dear, there is Mr. Epworth!”

“A common bow in passing will be enough to damp his pretensions,” said Mr. Beaumaris. “If that does not suffice, I will look at him through my glass.”

This made her give an involuntary gurgle of laughter, but an instant later she was serious again, and evidently struggling to find the words with which to express herself.

“What very awkward places we do choose in which to propose to one another!” remarked Mr. Beaumaris, guiding her gently towards a red-plush couch. “Let us hope that if we sit down, and appear to be engrossed in conversation no one will have the bad manners to interrupt us!”

“I do not know what you must think of me!” said Arabella.

“I expect I had better not tell you until we find ourselves in a more retired situation,” he replied. “You always blush so delightfully when I pay you compliments that it might attract attention to ourselves.”

She hesitated, and then turned resolutely towards him, tightly gripping her sunshade, and saying: “Mr. Beaumaris, you do indeed wish to marry me?”

“Miss Tallant, I do indeed wish to marry you!” he asserted.

“And—and you are so wealthy that my—my fortune can mean nothing to you?”

“Nothing at all, Miss Tallant.”

She drew an audible breath. “Then—will you marry me at once?” she asked.

Now, what the devil’s the meaning of this? thought Mr. Beaumaris, startled. Can that damned young cub have been getting up to more mischief since I left town?

“At once?” he repeated, voice and countenance quite impassive.

“Yes!” said Arabella desperately. “You must know that I have the greatest dislike of—of all formality, and—and the nonsense that always accompanies the announcement of an engagement! I—I should wish to be married very quietly—in fact, in the strictest secrecy—and before anyone has guessed—that I have accepted your very obliging offer!”

The wretched youth must have been deeper under the hatches than I guessed, thought Mr. Beaumaris, and still she dare not tell me the truth! Does she really mean to carry out this outrageous suggestion, or does she only think that she means it? A virtuous man would undoubtedly, at this juncture, disclose that there is not the smallest need for these measures. What very unamusing lives virtuous men must lead!

“You may think it odd of me, but I have always thought it would be so very romantic to elope!” pronounced Papa’s daughter defiantly.

Mr. Beaumaris, whose besetting sin was thought by many to be his exquisite enjoyment of the ridiculous, turned a deaf ear to the promptings of his better self, and replied instantly, “How right you are! I wonder I should not have thought of an elopement myself! The announcement of the engagement of two such notable figures as ourselves must provoke a degree of comment and congratulation which would not be at all to our taste!”

“Exactly so!” nodded Arabella, relieved to find that he saw the matter in so reasonable a light.

“Consider, too, the chagrin of such as Horace Epworth!” said Mr. Beaumaris, growing momently more enamoured of the scheme. “You would be driven to distraction by their ravings.”

“Well, I do think I might be,” said Arabella.

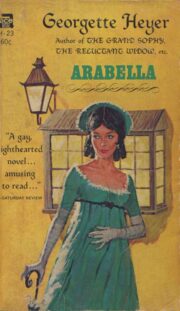

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.