He sounded much more like the younger brother she knew when he spoke like that, a scared look in his face, and in his voice an unreasoning dependence on her ability to help him out of a scrape.

“Bills don’t signify,” pronounced Mr. Scunthorpe. “Leave town: won’t be followed. Not been living under your own name. Gaining debts another matter. Got to raise the wind for that. Debt of honour.”

“I know it, curse you!”

“But all debts are debts of honour!” Arabella said. “Indeed, you should pay your bills first of all!”

A glance passed between the two gentleman, indicative of their mutual agreement not to waste breath in arguing with a female on a subject she would clearly never understand. Bertram passed his hand over his brow, heaving a short sigh, and saying: “There’s only one thing to be done. I have thought it all over, Bella, and I mean to enlist, under a false name. If they won’t have me as a trooper, I’ll join a line regiment. I should have done it yesterday, when I first thought of it, only that there’s something I must do first. Affair of honour. I shall write to my father, of course, and I daresay he will utterly cast me off, but that can’t be helped!”

“How can you think so?” Arabella cried hotly. “Grieved he must be—oh, I dare not even think of it!—but you must know that never, never would he do such an unchristian thing as to cast you off! Oh, do not write to him yet! Only give me tune to think what I can do! If Papa knew that you owed all that money, I am very sure he would pay every penny of it, though it ruined him!”

“How can you suppose I would be such a gudgeon as to tell him that? No! I shall tell him that my whole mind is set on the army, and I had as lief start in the ranks as not!”

This speech struck far more dismay into Arabella’s heart than his previous talk of committing suicide, for to take the King’s shilling seemed to her a likely thing for him to do. She uttered, hardly above a whisper: “No, no!”

“It must be, Bella,” he said, “I’m sure the army is all I’m fit for, and I cannot show my face again with a load of debt hanging over me. Particularly a debt of honour! O God, I think I must have been mad!” His voice broke, and he could not speak for a moment. In the end he contrived to summon up the travesty of a smile, and to say: “Pretty pair, ain’t we? Not that you did anything as wrong as I have.”

“Oh, I have behaved so dreadfully!” she exclaimed. “It is even my fault that you are reduced to these straits! Had I never presented you to Lord Wivenhoe—”

“That’s fudge!” he said quickly. “I had been to gaminghouses before I met him. He was not to know I wasn’t as well-blunted as that set of his! I ought not to have gone with him to the Nonesuch. Only I had lost money on a race, and I thought—I hoped Oh, talking pays no toll! But to say it was your fault is all gammon!”

“Bertram, who won your money at the Nonesuch?” she asked.

“The bank. It was faro.”

“Yes, but someone holds the bank!”

“The Nonpareil.”

She stared at him. “Mr. Beaumaris?” she gasped. He nodded. “Oh, no, do not say so! How could he have let you—No, no, Bertram!”

She sounded so much distressed that he was puzzled. “Why the devil shouldn’t he?”

“You are only a boy! He must have known! And to accept notes of hand from you! Surely he might have refused to do so much at least!”

“You don’t understand!” he said impatiently. “I went there with Chuffy, so why should he refuse to let me play?”

Mr. Scunthorpe nodded. “Very awkward situation, ma’am. Devilish insulting to refuse a man’s vowels.”

She could not appreciate the niceties of the code evidently shared by both gentlemen, but she could accept that they must obtain in male circles. “I must think it wrong of him,” she said. “But never mind! The thing is that he is—that I am particularly acquainted with him! Don’t be in despair, Bertram! I am persuaded that if I were to go to him, explain that you are not of age, and not a rich man’s son, he will forgive the debt!”

She broke off, for there was no mistaking the expressions of shocked disapprobation in both Bertram’s and Mr. Scunthorpe’s faces.

“Good God, Bella, what will you say next!”

“But, Bertram, indeed he is not proud and disagreeable, as so many people think him! I—I have found him particularly kind, and obliging!”

“Bella, this is a debt of honour! If it takes me my life long to do it, I must pay it, and so I shall tell him!”

Mr. Scunthorpe nodded judicial approval of this decision.

“Spend your life paying six hundred pounds to a man who is so wealthy that I daresay he regards it no more than you would a shilling?” cried Arabella. “Why, it is absurd!”

Bertram looked despairingly at his friend. Mr. Scunthorpe said painstakingly: “Nothing to do with it, ma’am. Debt of honour is a debt of honour. No getting away from that.”

“I cannot agree! I own, I do not like to do it, but I could do it, and I know he would never refuse me!”

Bertram grasped her wrist. “Listen, Bella! I daresay you don’t understand—in fact, I can see that you don’t!—but if you dared to do such a thing I swear you’d never see my face again! Besides, even if he did tear up my vowels I should still think myself under an obligation to redeem them! Next you will be suggesting that you should ask him to pay those damned tradesmen’s bills for me!”

She coloured guiltily, for some such idea had just crossed her mind. Suddenly, Mr. Scunthorpe, whose face a moment before had assumed a cataleptic expression, uttered three pregnant words. “Got a notion!”

The Tallants looked anxiously at him, Bertram with hope, his sister more than a little doubtfully.

“Know what they say?” Mr. Scunthorpe demanded. “Bank always wins!”

“I know that,” said Bertram bitterly. “If that’s all you have to say—”

“Wait!” said Mr. Scunthorpe. “Start one!” He saw blank bewilderment in the two faces confronting him, and added, with a touch of impatience: “Faro!”

“Start a faro-bank?” said Bertram incredulously. “You must be mad! Why, even if it were not the craziest thing I ever heard of, you can’t run a faro-bank without capital!”

“Thought of that,” said Mr. Scunthorpe, not without pride. “Go to my trustees. Go at once. Not a moment to be lost.”

“Good God, you don’t suppose they would let you touch your capital for such a cause as that?”

“Don’t see why not!” argued Mr. Scunthorpe. “Always trying to add to it. Preaching at me for ever about improving the estate! Very good way of doing it: wonder they haven’t thought of it for themselves. Better go and see my uncle at once.”

“Felix, you’re a gudgeon!” said Bertram irritably. “No trustee would let you do such a thing! And even if they would, good God, we neither of us want to spend our lives running a faro-bank!”

“Shouldn’t have to,” said Mr. Scunthorpe, sticking obstinately by his guns. “Only want to clear you of debt! One good night’s run would do it Close the bank then.”

He was so much enamoured of this scheme that it was some time before he could be dissuaded from trying to promote it. Arabella, paying very little heed to the argument, sat wrapped in her own thoughts. That these were by no means pleasant would have been apparent, even to Mr. Scunthorpe, had he been less engrossed in the championing of his own plans, for not only did her hands clench and unclench in her lap, but her face, always very expressive, betrayed her. But by the time Bertram had convinced Mr. Scunthorpe that a faro-bank would not answer, she was sufficiently mistress of herself again to excite no suspicion in either gentleman’s breast.

She turned her eyes towards Bertram, who had sunk back, after his animated argument, into a state of hopeless gloom. I shall think of something,” she said. “I know I shall contrive to help you! Only please, please do not enlist, Bertram! Not yet! Only if I should fail!”

“What do you mean to do?” he demanded. “I shan’t enlist until I have seen Mr. Beaumaris, and—and explained to him how it is! That I must do. I—I told him I had no funds in London, and should be obliged to send into Yorkshire for them, so he asked me to call at his house on Thursday. It is of no use to look at me like that, Bella! I couldn’t tell him. I was done-up, and had no means of paying him, with them all there, listening to what we were saying! I would have died rather! Bella, have you any money? Could you spare me enough to get my shirt back? I can’t go to see the Nonpareil like this!”

She thrust her purse into his hand. “Yes, yes, of course! If only I had not bought those gloves, and the shoes, and the new scarf! There are only ten guineas left, but it will be enough to make you more comfortable until I have thought how to help you, won’t it? Do, do remove from this dreadful house! I saw quite a number of inns on our way, and one or two of them looked to be respectable!”

It was plain that Bertram would be only too ready to change his quarters, and after a brief dispute, in which he was very glad to be worsted, he took the purse, gave her a hug, and said that she was the best sister in the world. He asked wistfully whether she thought Lady Bridlington might be induced to advance him seven hundred pounds, on a promise of repayment over a protracted period, but although she replied cheerfully that she had no doubt that she could arrange something of the sort, he could not deceive himself into thinking it possible, and sighed. Mr. Scunthorpe, prefixing his remark with one of his deprecating coughs, suggested that as the hackney had been told to wait for them, he and Miss Tallant, ought, perhaps, to be taking their leave. Arabella was much inclined to go at once in search of a suitable hostelry for Bertram, but was earnestly dissuaded, Mr. Scunthorpe promising to attend to this matter himself, and also to redeem Bertram’s raiment from the pawnbroker’s shop. The brother and sister then parted, clinging to one another in such a moving way that Mr. Scunthorpe was much affected by the sight, and had to blow his nose with great violence.

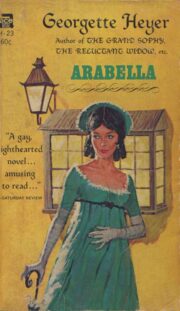

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.