Her colour rushed up again; she turned away her head in confusion, her lip slightly trembling. Mr. Beaumaris shut the fan, and gave it back to her. He said gently: “I am not, I hope, such a coxcomb as to distress you by repeated solicitations, Miss Tallant, but you may believe that I am still of the same mind as I was when I made you an offer. If your sentiments should undergo a change, one word-one look!—would be sufficient to apprise me of it.” She lifted her hand in a gesture imploring his silence. “Very well,” he said. “I shall say no more on that head. But if you should stand in need of a friend at any time, let me assure you that you may depend upon me.”

These words, delivered, as they were, in a more earnest tone than she had yet heard him use, almost made her heart stand still. She was tempted to take the risk of confessing the truth; hesitated, as the dread of seeing his expression change from admiration to disgust took possession of her; turned her eyes towards him; and then hurriedly rose to her feet, as another couple entered the conservatory. The moment was lost; she had time not only to recollect what might be the consequences if Mr. Beaumaris treated her second confidence with no more respect than he had treated her first; but also to recall every warning she had received of the danger of trusting him too far. Her heart told her that she might do so, but her scared brain recoiled from the taking of any step that might lead to exposure, and to disgrace.

She went back into the ballroom with him; he relinquished her to Sir Geoffrey Morecambe, who came up to claim her; and within a very few minutes had taken leave of his hostess, and left the party.

XIII

Bertram’s acquaintance with Lord Wivenhoe prospered rapidly. After a day spent together at the races, each was so well pleased with the other that further assignations were made. Lord Wivenhoe did not trouble to enquire into his new friend’s age, and Bertram naturally did not confess that he was only just eighteen years old. Wivenhoe drove him to Epsom in his curricle, with a pair of dashing bays harnessed in the bar, and finding that Bertram was knowledgeable on the subject of horseflesh, good-naturedly offered to hand over the ribbons to him. So well did Bertram handle the pair, and at such a spanking pace did he drive them, showing excellent judgment in the feathering of his corners, and catching the thong of his whip just as the Squire had taught him, that he needed no other passport to Wivenhoe’s favour. Any man who could control the kind of prime cattle his lordship liked must be a capital fellow. When he could do so without abating his cheerful conversation, he was clearly a right ’un, at home to a peg, and worthy of the highest regard. After some very interesting exchanges of reminiscences about incurable millers, roarers, lungers, half-bred blood-cattle, gingers, and slugs, which led inevitably to still more interesting stories of the chase, during the course of which both gentlemen found themselves perfectly in accord in their contempt of such ignoble persons as roadsters and skirters, and their conviction that the soundest of all maxims was, Get over the ground if it breaks your neck, formality was at an end between them, and his lordship was not only begging Bertram to call him Chuffy, as everyone else did, but promising to show him some of the rarer sights in town. Bertram’s fortunes, ever since he had come to London, had fluctuated in a bewildering manner. His first lucky evening with what he had swiftly learnt to refer to as St Hugh’s Bones had started him off on a career that seriously alarmed his staider friend, Mr. Scunthorpe. He had been encouraged by his luck to order a great many things from the various shops and warehouses where Mr. Scunthorpe was known, and although a hat from Baxter’s, a pair of boots from Hoby’s, a seal from Rundell and Bridge, and a number of trifling purchases, such as a walking cane, a pair of gloves, some neckcloths, and some pomade for his hair were none of them really expensive, he had discovered, with a slight shock, that when added together they reached rather an alarming total. There was also his bill at the inn to be taken into account, but since this had not so far been presented he was able to relegate it to the very back of his mind.

The success of that first evening’s play had not been repeated: in fact, upon the occasion of his second visit to the discreet house in Pall Mall he had been a substantial loser, and had been obliged to acknowledge that there might have been some truth in Mr. Scunthorpe’s dark warning. He was quite shrewd enough to realize that he had been a pigeon amongst hawks, but he was inclined to think that the experience would prove of immense value to him, since he was not one to be twice caught with the same lure. Playing billiards with Mr. Scunthorpe at the Royal Saloon, he was approached by an affable Irishman, who applauded his play, offered to set him a main or two, or to accompany him to a snug little ken where a penchant for faro, or rouge-et-noir could be enjoyed. It was quite unnecessary for Mr. Scunthorpe to whisper in his ear that this was a nibble from an ivory-turner: Bertram had no intention of going with the plausible Irishman, had scented a decoy the moment he saw him, and was very well-pleased with himself for being no longer a flat, but, on the contrary, a damned knowing one. A pleasantly convivial evening at Mr. Scunthorpe’s lodging, with several rubbers of whist to follow an excellent dinner, convinced him that he had a natural aptitude for cards, a belief that was by no means shaken by the vicissitudes of fortune which followed this initiation. It would be foolish, of course, to frequent gaming-hells, but once a man had made friends in town there were plenty of unexceptionable places where he could enjoy every form of gaming, from whist to roulette. On the whole, he rather thought he was lucky at the tables. He was quite sure that he was lucky on the Turf, for he had several very good days. It began to be a regular habit with him to look in at Tattersall’s, to watch how the sporting men bet their money there, and sometimes to copy them, in his modest way, or at others to back his own choice. When he became intimate with Chuffy Wivenhoe, he accompanied him often, either to advise him on the purchase of a prad, to watch some ruined man’s breakdown being sold, or to lay out his blunt on a forthcoming race. Once he had fallen into the way of going with Wivenhoe it was impossible to resist spending a guinea for the privilege of being made free of the subscription-room; and once the very safe man whom his lordship patronized saw the company he kept it was no longer necessary for him to do more than record his bets, just as the Bloods did, and wait for settling-day either to receive his gains, or to pay his losses. It was all so pleasant, and every day was so full of excitement, that it went to his head, and if he was sometimes seized by panic, and felt himself to be careering along at a pace he could no longer control, such frightening moments could not endure when Chuffy was summoning him to come and try the paces of a capital goer, or Jack Carnaby carrying him off to the theatre, or the Five-courts, or the Daffy Club. None of his new friends seemed to allow pecuniary considerations to trouble them, and since they all appeared to be constantly on the brink of ruin, and yet contrived, by some fortunate bet, or throw of the dice, to come about again, he began to fall insensibly into the same way of life, and to think that it was rustic to treat a temporary insolvency as more than a matter for jest. It did not occur to him that the tradesmen who apparently gave Wivenhoe and Scunthorpe unlimited credit would not extend the same consideration to a young man whose circumstances were unknown to them. The first hint he received of the different light in which he was regarded came in the form of a horrifying bill from Mr. Swindon. He could not believe at first that he could possibly have spent so much money on two suits of clothes and an overcoat, but there did not seem to be any disputing Mr. Swindon’s figures. He asked Mr. Scunthorpe, in an airy way, what he did if he could not meet his tailor’s account. Mr. Scunthorpe replied simply that he instantly ordered a new rig-out, but however much Bertram had been swept off his feet he retained enough native shrewdness to know that this expedient would not answer in his case. He tried to get rid of a very unpleasant feeling at the pit of his stomach by telling himself that no tailor expected to be paid immediately, but Mr. Swindon did not seem to be conversant with this rule. After a week he presented his bill a second time, accompanied by a courteous letter indicating that he would be much obliged by an early settlement of his account. And then, as though they had been in collusion with Mr. Swindon, other tradesmen began to send in their bills, so that in less than no time one of the drawers in the dressing-table in Bertram’s bedroom was stuffed with them. He managed to pay some of them, which made him feel much easier, but just as he was convincing himself that with the aid of a judicious bet, or a short run of luck, he would be able to clear himself from debt altogether, a polite but implacable gentleman called to see him, waited a good hour for him to come in from a ride in the Park, and then presented him with a bill which he said he knew had been overlooked. Bertram managed to get rid of him, but only by giving him some money on account, which he could ill-spare, and after an argument which he suspected was being listened to by the waiter hovering round the coffee-room door. This fear was shortly confirmed by the landlord’s sending up his account with the Red Lion next morning. Matters were becoming desperate, and only one way of averting disaster suggested itself to Bertram. It was all very well for Mr. Scunthorpe to advise against racing and gaming: what Mr. Scunthorpe did not understand was that merely to abstain from these pastimes would in no way solve the difficulty. If Mr. Scunthorpe found himself at Point Non Plus he had trustees who, however much they might rate him, would certainly come to his rescue. It was quite unthinkable that Bertram should appeal to his father for assistance: he would rather, he thought, cut his throat, for not only did the very thought of laying such a collection of bills before the Vicar appal him, but he knew very well that the settlement of them must seriously embarrass his father. Nor would it any longer be of any use to sell his watch, or that seal he had bought, or the fob that hung beside him from his waistband: in some inexplicable way his expenses seemed to have been growing ever larger since he had begun to frequent the company of men of fashion. A vague, and rather dubious notion of visiting a moneylender was vetoed by Mr. Scunthorpe, who told him that since the penalties attached to the lending of money at interest to minors were severe, not even Jew King could be induced to advance the smallest sum to a distressed client under age. He added that he had once tried that himself, but that the cents-per-cent were all as sharp as needles, and seemed to smell out a fellow’s age the moment they clapped eyes on him. He was concerned, though not surprised, to learn of Bertram’s having got into Queer Street, and had the quarter not been so far advanced that he himself was at a standstill, he would undoubtedly have offered his friend instant relief, for he was one, his intimates asserted, who dropped his blunt like a generous fellow. Unfortunately he had no blunt to drop, and knew from past experience that an application to his trustees would result in nothing but unfeeling advice to him to rusticate at his house in Berkshire, where his Mama would welcome him with open arms. To do him justice, Bertram would have been exceedingly reluctant to have accepted pecuniary assistance from any of his friends, since he saw no prospect, once he had returned to Yorkshire, of being able to reimburse them. There was only one way of getting clear, and that was the way of the Turf and Table. He knew it to be hazardous, but as he could not see that it was possible for him to be in a worse case than he was already, it was worth the risk. Once he had paid his debts he rather thought that he should bring his visit to London to an end, for although he had enjoyed certain aspects of it enormously, he by no means enjoyed insolvency, and was beginning to realize that to stand continually to the edge of a financial precipice would very soon reduce him to a nervous wreck. An interview with a creditor who was not polite at all, but, on the contrary, extremely threatening, had shaken him badly: unless he made a speedy recovery it could only be a matter of days before the tipstaffs would be on his heels, even as Mr. Scunthorpe had prophesied.

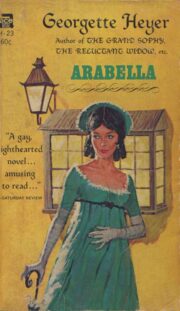

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.