“Very true!” She watched Ulysses look up adoringly into his face, and said: “I knew he would grow to be attached to you: only see how he looks at you!”

“His affection, Miss Tallant, threatens to become a serious embarrassment.”

“Nonsense! I am sure you must be fond of him, or you would not take him out with you!”

“If that is what you think, ma’am, you can have no idea of the depths to which he can sink to achieve his own ends. Blackmail is an open book to him. He is well aware that I dare not deny him, lest I should lose what little reputation I may have in your eyes.”

“How absurd you are! I knew, as soon as I saw how well you handled him, that you know just how to use a dog. I am so glad you have kept him with you.”

She gave Ulysses a last pat, and stepped back on to the flag-way. Mr. Beaumaris said: “Will you not give me the pleasure of driving you to your door?”

“No, indeed, It is only a step!”

“No matter, send your maid home! Ulysses adds his entreaties to mine.”

As Ulysses chose this moment to scratch one ear, this made her laugh.

“Mere bashfulness,” explained Mr. Beaumaris, stretching down his hand. “Come!”

“Very well—since Ulysses wishes it so much!” she said, taking his hand, and climbing into the curricle. “Mr. Beaumaris will see me home, Maria.”

He spread a light rug across her knees, and said over his shoulder: “I have recalled, Clayton, that I need something from the chemist’s. Go and buy me a—a gum-plaster! You may walk home.”

“Very good, sir,” said the groom, at his most wooden, and sprang down into the road.

“A gum-plaster?” echoed Arabella, turning wide eyes of astonishment upon Mr. Beaumaris. “What in the world can you want with such a thing, sir?”

“Rheumatism,” said Mr. Beaumaris defiantly, setting his horses in motion—

“You? Oh, no, you must be quizzing me!”

“Not at all. I was merely seeking an excuse to be rid of Clayton. I hope Ulysses will prove himself an adequate chaperon. I have something to say to you, Miss Tallant, for which I do not desire an audience.”

She had been stroking the dog, but her hands were stilled at this, and the colour receded from her cheeks. Rather breathlessly, she asked: “What is it?”

“Will you do me the honour of becoming my wife?”

She was stunned, and for a moment could not utter a word. When she was able to control her voice a little, she said: “I think you must be quizzing me.”

“You must know that I am not.”

She trembled. “Yes, yes, let us say that that was all it was, if you please! I am very much obliged to you, but I cannot marry you!”

“May I know why you cannot, Miss Tallant?”

She was afraid that she was about to burst into tears, and answered in a shaken tone: “There are many reasons. Pray believe it is impossible!”

“Are you quite sure that these reasons are insuperable?” he asked.

“Quite, quite sure! Oh, please do not urge me further! I had never dreamed—it never entered my head—I would not for the world have given you cause to suppose—Oh, please say no more, sir!”

He bowed, and was silent. She sat staring down at her clasped hands in great agitation of spirit, her mind in a turmoil, tossed between surprise at such a declaration, coming from one whom she had believed to have been merely amusing himself, and the shock of realizing, for the first time, that there was no one she would rather marry than Mr. Beaumaris.

After a slight pause, he said in his usual calm way: “I believe there is always a little awkwardness attached to such situations as this in which we now find ourselves. We must strive not to allow it to overcome us. Is Lady Bridlington’s ball to rank amongst the season’s greatest squeezes?”

She was grateful to him for easing the tension, and all the discomfort of the moment, and tried to reply naturally. “Yes, indeed, it is! I am sure quite three hundred cards of invitation have been sent out. Shall—shall you find time to look in, I wonder?”

“Yes, and shall hope that even though you will not marry me you may be persuaded to dance with me.”

She replied she scarcely knew what: it was largely inaudible. He shot a quick look at her averted profile, hesitated, and then said nothing. They had reached Park Street by this time, and in another moment he had handed her down from the curricle.

“Do not come with me to the door! I know you do not like to leave your horses!” she said, in a hurried tone. “Goodbye! I shall see you at the ball.”

He waited until he had seen her admitted into the house, and then got into the curricle again, and drove off. Ulysses nudged his nose under his arm. “Thank you,” he said dryly. “Do you think I am unreasonable to wish that she would trust me enough to tell me the truth?”

Ulysses sighed heavily; he was rather sleepy after his day in the country.

“I suppose I shall end by telling her that I have known it all along. And yet—Yes, Ulysses, I am quite unreasonable. Did it seem to you that she was not as indifferent to me as she would have had me believe?”

Understanding that something was expected of him, his admirer uttered a sound between a yelp and a bark, and furiously wagged his tail.

“You feel that I should persevere?” said Mr. Beaumaris. “I was, in fact, too precipitate. You may be right. But if she had cared at all, would she not have told me the truth?”

Ulysses sneezed.

“At all events,” remarked Mr. Beaumaris, “she was undoubtedly pleased with me for bringing you out with me.”

Whether it was due to this circumstance, or to Ulysses’ unshakeable conviction that he was born to be a carriage-dog, Mr. Beaumaris continued to take him about. Those of his intimates who saw Ulysses, once they had recovered from the initial shock, were of the opinion that the Nonpareil was practising some mysterious jest on society, and only one earnest imitator went so far as to adopt an animal of mixed parentage to ride in his own carriage. He thought that if the Nonpareil was setting a new fashion it would become so much the rage that it might be difficult hereafter to acquire a suitable mongrel. But Mr. Warkworth, a more profound thinker, censured this act as being rash and unconsidered. “Remember when the Nonpareil wore a dandelion in his buttonhole three days running?” he said darkly. “Remember the kick-up there was, with every saphead in town running round to all the flower-women for dandelions, which they hadn’t got, of course. Stands to reason you couldn’t buy dandelions! Why, poor Geoffrey drove all the way to Esther looking for one, and Altringham went to the trouble of rooting up half-a-dozen out of Richmond Park, and having a set-to with the keeper over it, and then planting ’em in his window-boxes. Good idea, if they had become the mode: clever fellow, Altringham!—but of course the Nonpareil was only hoaxing us! Once he had the whole lot of us decked out with them, he never wore one again, and a precious set of gudgeons we looked! Playing the same trick again, if you ask me!”

Only in one quarter did unhappy results arise from the elevation of Ulysses. The Honourable Frederick Byng, who had for years been known by the sobriquet of Poodle Byng from his habit of driving everywhere with a very highly-bred and exquisitely shaved poodle sitting up beside him, encountered Mr. Beaumaris in Piccadilly one afternoon, and no sooner clapped eyes on his disreputable companion than he pulled up his horses all standing, and spluttered out: “What the devil—!

Mr. Beaumaris reined in his own pair, and looked enquiringly over his shoulder. Mr. Byng, his florid countenance suffused by an angry flush, was engaged in backing his curricle, jabbing at his horses’ mouths in a way that showed how greatly moved he was. Once alongside the other curricle, he glared at Mr. Beaumaris, and demanded an explanation.

“Explanation of what?” said Mr. Beaumaris. “If you don’t take care, you’ll go off in an apoplexy one of these days, Poodle! What’s the matter?”

Mr. Byng pointed a trembling finger at Ulysses. “What’s the meaning of that?” he asked belligerently. “If you think I’ll swallow any such damned insult—!”

He was interrupted. The two dogs, who had been eyeing one another measuringly from their respective vehicles, suddenly succumbed to a mutual hatred, uttered two simultaneous snarls, and leaped for one another’s throats. Since the curricles were too far apart to allow them to come to grips, they were obliged to vent their feelings in a series of hysterical objurgations, threats, and abuse, which drowned the rest of Mr. Byng’s furious speech.

Mr. Beaumaris, holding Ulysses by the scruff of his neck, laughed so much that he could hardly speak: a circumstance which did nothing to mollify the outraged Mr. Byng. He began to say that he should know how to answer an attempt to make him ridiculous, but was obliged to break off in order to command his dog to be quiet.

“No, no, Poodle, don’t call me out!” said Mr. Beaumaris, his shoulders still shaking. “Really, I had no such intention! Besides, we should only make fools of ourselves, going out to Paddington in the cold dawn to exchange shots over a pair of dogs!”

Mr. Byng hesitated. There was much in what Mr. Beaumaris said; moreover, Mr. Beaumaris was acknowledged to be one of the finest shots in England, and to call him out for a mere trifle would be an act of sheer foolhardiness. He said suspiciously: “If you’re not doing it to make a laughingstock of me, why are you doing it?”

“Hush, poodle, hush! You are treading on delicate ground!” said Mr. Beaumaris. “I cannot bandy a lady’s name about in the open street!”

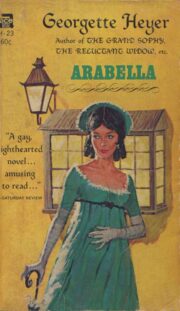

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.