“Good God, no!”

“Oh, so that’s yet another idiot who’s wearing the willow for you, is it?” said her grace, who had her own ways of discovering what was going on in the world from which she had retired. “Who is it now? One of these days you’ll go a step too far, mark my words!”

“I think I have,” said Mr. Beaumaris.

She stared at him, but before she could speak her butler had entered the room, staggering under a specimen of the ducal plate which her grace had categorically refused to relinquish to the present Duke, on the twofold score that it was her personal property, and that he shouldn’t have married anyone who gave his mother such a belly-ache as that die-away ninny he had set in her place. This impressive tray Hadleigh set down on the table, casting, as he did so, a very impressive look at Mr. Beaumaris. Mr. Beaumaris nodded his understanding, and rose, and went to pour out the wine. He handed his grandmother a modest half-glass, to which she instantly took exception, demanding to know whether he had the impertinence to suppose that she could not carry her wine.

“I daresay you can drink me under the table,” replied Mr. Beaumaris, “but you know very well it’s extremely bad for your health, and also that you cannot bully me into pandering to your outrageous commands.” He then lifted her disengaged hand to his lips, and said gently: “You are a rude and an overbearing old woman, ma’am, but I hope you may live to be a hundred, for I like you so much better than any other of my relatives!”

“I daresay that’s not saying much,” she remarked, rather pleased by this audacious speech. “Sit down again, and don’t try to hoax me with any of your taradiddles! I can see you’re going to make a fool of yourself, so you needn’t wrap it up in clean linen! You haven’t come here to tell me you’re going to marry that brass-faced lightskirt you had in keeping when I last saw you?”

“I have not!” said Mr. Beaumaris.

“Just as well, for laced mutton being brought into the family is what I won’t put up with! Not that I think you’re fool enough for that.”

“Where do you learn your abominable expressions, ma’am?” demanded Mr. Beaumaris.

“I don’t belong to your mealy-mouthed generation, thank God! Who is she?”

“If I did not know from bitter experience, ma’am, that nothing occurs in London but what you are instantly aware of it, I should say that you had never heard of her. She is—or at any rate, she says she is—the latest heiress.”

“Oh! Do you mean the chit that that silly Bridlington woman, has staying with her? I’m told she’s a beauty.”

“She is beautiful,” acknowledged Mr. Beaumaris. “But that’s not it.”

“Well, what is it?”

He reflected. “She is the most enchanting little wretch I ever encountered,” he said. “When she is trying to convince me that she is up to every move in the social game, she contrives to appear much like any other female, but when, as happens all too often for my comfort, her compassion is stirred, she is ready to go to any lengths to succour the object of her pity. If I marry her, she will undoubtedly expect me to launch a campaign for the alleviation of the lot of climbing-boys, and will very likely turn my house into an asylum for stray curs.”

“Oh, she will, will she?” said her grace, staring at him with knit brows. “Why?”

“Well, she has already foisted a specimen of each on to me,” he explained. “No, perhaps I wrong her. Ulysses she certainly foisted on to me, but the unspeakable Jemmy I actually offered to take under my protection.”

The Duchess brought her hand down on the arm of her chair. “Stop trying to gammon me!” she commanded. “Who is Ulysses, and who is Jemmy?”

“I have already offered to make you a present of Ulysses,” Mr. Beaumaris reminded her. “Jemmy is a small climbing-boy whose manifest wrongs Miss Tallant is determined to set right. I wish you might have heard her telling Bridlington that he cared for nothing but his own comfort, like all the rest of us; and asking poor Charles Fleetwood to imagine what his state might now be had he been reared by a drunken foster-mother, and sold into slavery to a sweep. Alas that I was not privileged to witness her encounter with the sweep! I understand that she drove him from the house with threats of prosecution. I am not at all surprised that he cowered before her: I have seen her disperse a group of louts.”

“She sounds to me an odd sort of a gal,” remarked her grace. “Is she a lady?”

“Unquestionably.”

“Who’s her father?”

“That, ma’am, is a mystery I have hopes that you may be able to unravel.”

“I?” she exclaimed. “I don’t know what you think I can tell you!”

“I have reason to believe that her home is within easy reach of Harrowgate, ma’am, and I recall that you visited that watering-place not so very long ago. You may have seen her at an Assembly—I suppose they do have Assemblies at Harrowgate?—or have heard her family spoken of.”

“Well, I didn’t!” replied her grace bitterly. “What’s more I don’t want to hear anything more about Harrowgate! A nasty, cold, shabby-genteel place, with the filthiest waters I ever tasted in my life! They did me no good at all, as anyone but a fool like that snivelling leech of mine would have known from the outset! Assemblies, indeed! It’s no pleasure to me to watch a parcel of country-dowds dancing this shameless waltz of yours! Dancing! I could give you another name for it!”

“I have no doubt that you could, ma’am, but I must beg you to spare my blushes! Moreover, for one who is for ever railing against the squeamishness of the modern miss, your attitude towards the waltz seems a trifle inconsistent”

“I don’t know anything about consistency,” retorted her grace, with perfect truth, “but I do know indecency when I see it!”

“We are wandering from the point,” said Mr. Beaumaris firmly.

“Well, I never met any Tallants in Harrowgate, or anywhere else. When I wasn’t trying to swallow something that no one is ever going to make me believe wasn’t drained off from the kennels, I was sitting watching your aunt knot a fringe in the most uncomfortable hole of a lodging I’ve been in yet! Why, I had to take all my own bed-linen with me!”

“You always do, ma’am,” said Mr. Beaumaris, who had several times been privileged to see the start of one of the Duchess’s impressive journeys. “Also your own plate, your favourite chair, your steward, your—”

“I don’t want any of your impudence, Robert!” interrupted her grace. “I don’t always have to take ’em!” She gave her shawl a twitch. “It’s nothing to me whom you marry,” she said. “But why you must needs dangle after a wealthy woman beats me!”

“Oh, I don’t think she has any fortune at all!” replied Mr. Beaumaris coolly. “She only said she had to put me in my place.”

He came under her eagle-stare again. “Put you in your place? Are you going to tell me, sir, that she ain’t tumbling over herself to catch you?”

“Far from it. She holds me at arm’s length. I cannot even be sure that she has even the smallest tendre for me.”

“Been seen in your company often enough, hasn’t she?” said her grace sharply.

“Yes, she says it does her a great deal of good socially to be seen with me,” said Mr. Beaumaris pensively.

“Either she’s a devilish deep ’un,” said her grace, a gleam in her eye, “or she’s a good gal! Lord, I didn’t think there was one of these nimmy-piminy modern gals alive that had enough spirit not to toadeat you! Should I like her?”

“Yes, I think you would, but to tell you the truth, ma’am, I don’t care a button whether you like her or not.”

Surprisingly, she took no exception to this, but nodded, and said: “You’d better marry her. Not if she ain’t of gentle blood, though. You ain’t a Caldicot of Wigan, but you come of good stock. I wouldn’t have let your mother marry into your family if it hadn’t been one of the best—not for five times the settlements your father made on her!” She added reminiscently: “A fine gal, Maria: I liked her better than any other of my brats.”

“So did I,” agreed Mr. Beaumaris, rising from his chair. “Shall I propose to Arabella, risking a rebuff, or shall I address myself to the task of convincing her that I am not the incorrigible flirt she has plainly been taught to think me?”

“It’s no use asking me,” said her grace unhelpfully. “It wouldn’t do you any harm to get a good set-down, but I don’t mind your bringing the gal to see me one day.” She held out her hand to him, but when he had punctiliously kissed it, and would have released it, her talon-like fingers closed on his, and she said: “Out with it, sir! What’s vexing you, eh?”

He smiled at her. “Not precisely that, ma’am—but I have the stupidest wish that she would tell me the truth!”

“Pooh, why should she?”

“I can think of only one reason, ma’am. That is what vexes me!” said Mr. Beaumaris.

XII

On his way home from Wimbledon, Mr. Beaumaris drove up Bond Street, and was so fortunate as to see Arabella, accompanied by a prim-looking maidservant, come out of Hookham’s Library. He pulled up immediately, and she smiled, and walked up to the curricle, exclaiming: “Oh, how much better he looks! I told you he would! Well, you dear little dog, do you remember me, I wonder?”

Ulysses wagged his tail in a perfunctory manner, suffered her to stretch up a hand to caress him, but yawned.

“For heaven’s sake, Ulysses, try to acquire a little polish!” Mr. Beaumaris admonished him.

Arabella laughed. “Is that what you call him? Why?”

“Well, he seemed, on the evidence, to have led a roving life, and judging by the example we saw it must have been adventurous,” explained Mr. Beaumaris.

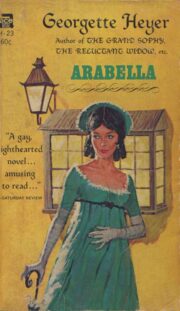

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.