A close inspection of such sprigs of fashion as were to be seen at the Fives-court made Bertram very glad to think he had bespoken a new coat, and he confided to Mr. Scunthorpe that he would not visit the haunts of fashion until his clothes had been sent home. Mr. Scunthorpe thought this a wise decision, and, as it was of course absurd to suppose that Bertram should kick his heels at the City inn which enjoyed his patronage, he volunteered to show him how an evening full of fun and gig could be spent in less exalted circles. This entertainment, beginning as it did in the Westminster Pit, where it seemed to the staring Bertram that representatives of every class of society, from the Corinthian to the dustman, had assembled to watch a contest between two dogs; and proceeding by way of the shops of Tothill Fields, where adventurous bucks tossed off noggins of Blue Ruin, or bumpers of heavy wet, in company with bruisers, prigs, coal-heavers, Nuns, Abbesses, and apple-women, to a coffee-shop, ended in the watch-house, Mr. Scunthorpe having become bellicose under the influence of his potations. Bertram, quite unused to such quantities of liquor as he had imbibed, was too much fuddled to have any very clear notion of what circumstance it was that had excited his friend’s wrath, though he had a vague idea that it was in some way connected with the advances being made by a gentleman in Petersham trousers towards a lady who had terrified him earlier in the proceedings by laying a palpable lure for him. But when a mill was in progress it was not his part to enquire into the cause of it, but to enter into the fray in support of his cicerone. Since he was by no means unlearned in the noble art of self-defence, he was able to render yeoman service to Mr. Scunthorpe, no proficient, and was in a fair way to milling his way out of the shop when the watch, in the shape of several Charleys, all springing their rattles, burst in upon them and, after a spirited set-to, over-powered the two peacebreakers, and hailed them off to the watch-house. Here, after considerable parley, conducted for the defence by the experienced Mr. Scunthorpe, they were admitted to bail, and warned to present themselves next day in Bow Street, not a moment later than twelve o’clock. The night-constable then packed them both into a hackney, and they drove to Mr. Scunthorpe’s lodging in Clarges Street, where Bertram passed what little was left of the night on the sofa in his friend’s sitting-room. He awoke later with a splitting headache, no very clear recollection of the late happenings, but a lively dread of the possible consequences of what he feared had been a very bosky evening. However, when Mr. Scunthorpe’s man had revived his master, and he emerged from his bedchamber, he was soon able to allay any such misgivings. “Nothing to be in a fret for, dear boy!” he said. “Been piloted to the lighthouse scores of times! Watchman will produce broken lantern in evidence—they always do it!—you give false name, pay fine, and all’s right!”

So, indeed, it proved, but the experience a little shocked the Vicar’s son. This, coupled with the extremely unpleasant after-effects of drinking innumerable flashes of lightning, made him determine to be more circumspect in future. He spent several days in pursuing such harmless amusements as witnessing a badger drawn in a menagerie in Holborn, losing his heart to Miss O’Neill from a safe position in the pit, and being introduced by Mr. Scunthorpe into Gentleman Jackson’s exclusive Boxing School in Bond Street. Here he was much impressed by the manners and dignity of the proprietor (whose decision in all matters of sport, Mr. Scunthorpe informed him, was accepted as final by patrician and plebeian alike), and was gratified by a glimpse of such notable amateurs as Mr. Beaumaris, Lord Fleetwood, young Mr. Terrington, and Lord Withernsea. He had a little practise with the single-stick with one of Jackson’s assistants, felt himself honoured by receiving a smiling word of encouragement from the great Jackson himself, and envied the assurance of the Goers who strolled in, exchanged jests with Jackson, who treated them with the same degree of civility as he showed to his less exalted pupils, and actually enjoyed bouts with the ex-champion himself. He was quick to see that no consideration of rank or consequence was enough to induce Jackson to allow a client to plant a hit upon his person, unless his prowess deserved such a reward; and from having entered the saloon with a feeling of superiority he swiftly reached the realization that in the Corinthian world excellence counted for more than lineage. He heard Jackson say chidingly to the great Nonpareil himself (who stripped to remarkable advantage, he noticed) that he was out of training; and from that moment his highest ambition was to put on the gloves with this peerless master of the art.

At the end of a week, Mr. Swindon, urged thereto by Mr. Scunthorpe, delivered the new clothes, and after purchasing such embellishments to his costume as a tall cane, a fob, and a Marseilles waistcoat, Bertram ventured to show himself in the Park, at the fashionable hour of five o’clock. Here he had the felicity of seeing Lord Coleraine, Georgy a Cockhorse, prancing down Rotten Row on his mettlesome steed; Lord Morton, on his long-tailed gray; and, amongst the carriages, Tommy Onslow’s curricle; a number of dashing gigs and tilburies; the elegant barouches of the ladies; and Mr. Beaumaris’s yellow-winged phaeton-and-four, which he appeared to be able to turn within a space so small as to seem impossible to any mere whipster. Nothing would do for Bertram after that but to repair to the nearest jobmaster’s stables, and to arrange for the hire of a showy chestnut hack. Whatever imperfections might attach to the bearing and style of a young gentleman from the country, Bertram knew himself to be a bruising rider, and in this guise determined to show himself to the society which his sister already adorned.

As luck would have it, he encountered her on the day when he first sallied forth, mounted upon his hired hack. She was sitting up beside Mr. Beaumaris in his famous phaeton, animatedly describing to him the scene of the Drawing-room in which she had taken humble part. This event had necessarily occupied her thoughts so much during the past week that she had been able to spare very few for the activities of her adventurous brother. But when she caught sight of him, trotting along on his chestnut hack, she exclaimed, and said impulsively: “Oh, it is—Mr. Anstey! Do pray stop, Mr. Beaumaris!”

He drew up his team obediently, while she waved to Bertram. He brought his hack up to the phaeton, and bowed politely, only slightly quizzing her with his eyes. Mr. Beaumaris, glancing indifferently at him, caught this arch look, became aware of a slight tension in the trim figure beside him, and looked under his lazy eyelids from one to the other.

“How do you do? How do you go on?” said Arabella, stretching out her hand in its glove of white kid.

Bertram bowed over it very creditably, and replied: “Famously! I mean to come—I mean to visit you some morning, Miss Tallant!”

“Oh, yes, please do!” Arabella looked up at her escort,, blushed and stammered: “May I p-present Mr. Anstey to you, Mr. Beaumaris? He—he is a friend of mine!”

“How do you do?” responded Mr. Beaumaris politely. “From Yorkshire, Mr. Anstey?”

“Oh, yes! I have known Miss Tallant since I was in short coats!” grinned Bertram.

“You will certainly be much envied by Miss Tallant’s numerous admirers,” responded Mr. Beaumaris. “Are you staying in town?”

“Just a short visit, you know!” Bertram’s gaze reverted to the team harnessed to the phaeton, all four of them on the fret. “I say, sir, that’s a bang-up team you have in hand!” he said, with all his sister’s impulsiveness. “Oh, don’t look at this hack of mine—showy, but I never crossed a greater slug in my life!”

“You hunt, Mr. Anstey?”

“Yes, with my uncle’s pack, in Yorkshire. Of course, it is not like the Quorn country, or the Pytchley, but we get some pretty good runs, I can tell you!” Bertram confided.

“Mr. Anstey,” interrupted Arabella, fixing him with a very compelling look, “I think Lady Bridlington has sent you a card for her ball: I hope you mean to come!”

“Well, you know, Bel—Miss Tallant!” said Bertram, with disastrous lack of gallantry, “that sort of mummery is not much in my line!” He perceived an anguished expression in her eyes, and added hastily: “That is, delighted, I am sure! Yes, yes, I shall be there! And I shall hope to have the honour of standing up with you!” he ended punctiliously.

Mr. Beaumaris was obliged to pay attention to his team, but he did not miss the minatory note in Arabella’s voice as she said: “I collect we are to have the pleasure of receiving a visit from you tomorrow, sir!”

“Oh!” said Bertram. “Yes, of course! As a matter of fact, I shall be taking a look-in at Tattersall’s, but—Yes, to be sure! I’ll come to visit you all right and tight!”

He then doffed his new hat, and bowed, and rode off at an easy canter. Arabella appeared to be conscious that some explanation was called for. She said airily: “You must know, sir, that we have been brought up almost as—as brother and sister!”

“I thought perhaps you had,” responded Mr. Beaumaris gravely.

She glanced sharply up at his profile. He seemed to be wholly absorbed in the task of manoeuvring the phaeton through a gap between a dowager’s landaulet and a smart barouche with a crest on the panel. She reassured herself with the reflection that whereas she favoured her Mama, Bertram was said to be the image of what the Vicar had been at the same age, and said: “But I was telling you about the Drawing-room, and how graciously the Princess Mary smiled at me! She was wearing the most magnificent toilet I ever saw in my life! Lady Bridlington tells me that when she was young she was thought to be the most handsome of all the princesses. I thought she looked to be very good-natured.”

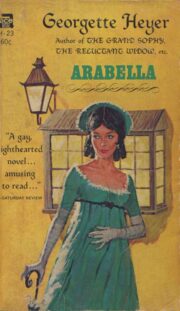

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.