“He is badly bruised, and has one or two nasty sores, but there are no bones broken,” Mr. Beaumaris said, straightening himself. He turned to where the two remaining youths were standing, poised on the edge of flight, and said sternly: “Whose dog is this?”

“It don’t belong to no one,” he was sullenly informed. “It goes all over, stealing things off of the rubbish-heaps: yes, and out of the butcher’s shop!”

“I seen ’im in Chelsea onct with ’alf a loaf of bread,” corroborated the other youth.

The accused crawled to Mr. Beaumaris’s elegantly shod feet, and pawed one gleaming Hessian appealingly.

“Oh, see how intelligent he is!” cried Arabella, stooping to fondle the animal. “He knows he has you to thank for his rescue!”

“If he knows that, I think little of his intelligence, Miss Tallant,” said Mr. Beaumaris, glancing down at the dog. “He certainly owes his life to you!”

“Oh, no! I could never have managed without your help! Will you be so obliging as to hand him up to me, if you please?” said Arabella, prepared to climb into the curricle again.

Mr. Beaumaris looked from her to the unkempt and filthy mongrel at his feet, and said: “Are you quite sure that you want to take him with you, ma’am?”

“Why, of course! You do not suppose that I would leave him here, for those wretches to torment as soon as we were out of sight! Besides, you heard what they said! He has no master—no one to feed him, or take care of him! Please give him to me!”

Mr. Beaumaris’s lips twitched, but he said with perfect gravity: “Just as you wish, Miss Tallant!” and picked up the dog by the scruff of his neck. He saw Miss Tallant’s arms held out to receive her new protégé, and hesitated. “He is very dirty, you know!”

“Oh, what does that signify? I have soiled my dress already, with kneeling on the flag-way!” said Arabella impatiently.

So Mr. Beaumaris deposited the dog on her lap, received his whip and gloves from her again, and stood watching with a faint smile while she made the dog comfortable, and stroked its ears, and murmured soothingly to it. She looked up. “What do we wait for, sir?” she asked, surprised.

“Nothing at all, Miss Tallant!” he said, and got into the curricle.

Miss Tallant, continuing to fondle the dog, spoke her mind with some force on the subject of persons who were cruel to animals, and thanked Mr. Beaumaris earnestly for his kindness in knocking the horrid boys’ heads together, a violent proceeding which seemed to have met with her unqualified approval. She then occupied herself with talking to the dog, and informing him of the splendid dinner he should presently be given, and the warm bath which he would (she said) so much enjoy. But after a time she became a little pensive, and relapsed into meditative silence.

“What is It, Miss Tallant?” asked Mr. Beaumaris, when she showed no sign of breaking the silence.

“Do you know,” she said slowly, “I have just thought—Mr. Beaumaris, something tells me that Lady Bridlington may not like this dear little dog!”

Mr. Beaumaris waited in patient resignation for his certain fate to descend upon him.

Arabella turned impulsively towards him. “Mr. Beaumaris, do you think—would you—?”

He looked down into her anxious, pleading eyes, a most rueful twinkle in his own. “Yes, Miss Tallant,” he said. “I would.”

Her face broke into smiles. “Thank you!” she said. “I knew I might depend upon you!” She turned the mongrel’s head gently towards Mr. Beaumaris. “There, sir! that is your new master, who will be very kind to you! Only see how intelligently he looks, Mr. Beaumaris! I am sure he understands. I daresay he will grow to be quite devoted to you!”

Mr. Beaumaris looked at the animal, and repressed a shudder. “Do you think so indeed?” he said.

“Oh, yes! He is not, perhaps, a very beautiful little dog, but mongrels are often the cleverest of all dogs.” She smoothed the creature’s rough head, and added innocently: “He will be company for you, you know. I wonder you do not have a dog already.”

“I do—in the country,” lie replied.

“Oh, sporting dogs! They are not at all the same.”

Mr. Beaumaris, after another look at his prospective companion, found himself able to agree with this remark with heartfelt sincerity.

“When he has been groomed, and has put some flesh on his bones,” pursued Arabella, serene in the conviction that her sentiments were being shared, “he will look very different. I am quite anxious to see him in a week or two!”

Mr. Beaumaris drew up his horses outside Lady Bridlington’s house! Arabella gave the dog a last pat, and set him on the seat beside his new owner, bidding him stay there. He seemed a little undecided at first, but being too bruised and battered to leap down into the road, he did stay, whining loudly. However, when Mr. Beaumaris, having handed Arabella up to the door, and seen her admitted into the house, returned to his curricle, the dog stopped whining, and welcomed him with every sign of relief and affection.

“Your instinct is at fault,” said Mr. Beaumaris. “Left to myself, I should abandon you to your fate. That, or tie a brick round your neck, and drown you.”

His canine admirer wagged a doubtful tail, and cocked an ear. “You are a disgraceful object!” Mr. Beaumaris told him. “And what does she expect me to do with you?” A tentative paw was laid on his knee. “Possibly, but let me tell you that I know your sort! You are a toadeater, and I abominate toadeaters. I suppose, if I sent you into the country my own dogs would kill you on sight.”

The severity in his tone made the dog cower a little, still looking up at him with the expression of a dog anxious to understand.

“Have no fear!” Mr. Beaumaris assured him, laying a fleeting hand on his head. “She clearly wishes me to keep you in town. Did it occur to her, I wonder, that your manners, I have no doubt at all, leave much to be desired? Do your wanderings include the slightest experience of the conduct expected of those admitted into a gentleman’s house? Of course they do not!” A choking sound from his groom, made him say over his shoulder: “I hope you like dogs, Clayton, for you are going to wash this specimen.”

“Yes, sir,” said his grinning attendant.

“Be very kind to him!” commanded Mr. Beaumaris. “Who knows? he may take a liking to you.”

But at ten o’clock that evening, Mr. Beaumaris’s. butler, bearing a tray of suitable refreshments to the library, admitted into the room a washed, brushed, and fed mongrel, who came in with something as near a prance as could be expected of one in his emaciated condition. At sight of Mr. Beaumaris, seeking solace from his favourite poet in a deep winged chair by the fire, he uttered a shrill bark of delight, and reared himself up on his hind legs, his paws on Mr. Beaumaris’s knees, his tail furiously wagging, and a look of beaming adoration in his eyes.

Mr. Beaumaris lowered his Horace. “Now, what the devil—?” he demanded.

“Clayton brought the little dog up, sir,” said Brough. “He said as you would wish to see how he looked. It seems, sir, that the dog didn’t take to Clayton, as you might say. Very restless, Clayton informs me, and whining all the evening.” He watched the dog thrust his muzzle under Mr. Beaumaris’s hand, and said: “It’s strange the way animals always go to you, sir. Quite happy now, isn’t he?”

“Deplorable,” said Mr. Beaumaris. “Down, Ulysses! Learn that my pantaloons were not made to be pawed by such as you!”

“He’ll learn quick enough, sir,” remarked Brough, setting a glass and a decanter down on the table at his master’s elbow. “You can see he’s as sharp as he can stare. Would there be anything more, sir?”

“No, only give this animal back to Clayton, and tell him I am perfectly satisfied with his appearance.”

“Clayton’s gone off, sir. I don’t think he can have understood that you wished him to take charge of the little dog,” said Brough.

“I don’t think he can have wanted to understand it,” said Mr. Beaumaris grimly.

“As to that, sir, I’m sure I couldn’t say. I doubt whether the dog will settle down with Clayton, him not having a way with dogs like he has with horses. I’m afraid he’ll fret, sir.”

“Oh, my God!” groaned Mr. Beaumaris. “Then take him down to the kitchen!”

“Well, sir, of course—if you say so!” replied Brough doubtfully. “Only there’s Alphonse.” He met his master’s eye, apparently had no difficulty in reading the question in it,, and said: “Yes, sir. Very French he has been on the subject. Quite shocking, I’m sure, but one has to remember that foreigners are queer, and don’t like animals.”

“Very well,” said Mr. Beaumaris, with a resigned sigh. “Leave him, then!”

“Yes, sir,” said Brough, and departed.

Ulysses, who had been thoroughly, if a little timidly, inspecting the room during this exchange, now advanced to the hearth-rug again, and paused there, suspiciously regarding the fire. He seemed to come to the conclusion that it was not actively hostile, for after a moment he curled himself up before it, heaved a sigh, laid his chin on Mr. Beaumaris’s crossed ankles, and disposed himself for sleep.

“I suppose you imagine you are being a companion to me,” said Mr. Beaumaris.

Ulysses flattened his ears, and gently stirred his tail.

“You know,” said Mr. Beaumaris, “a prudent man would draw back at this stage.”

Ulysses raised his head to yawn, and then snuggled it back on Mr. Beaumaris’s ankles, and closed his eyes.

“You may be right,” admitted Mr. Beaumaris. “But I wonder what next she will saddle me with?”

X

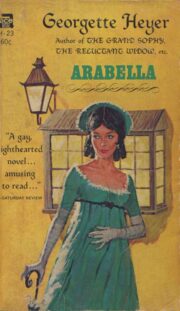

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.