The urchin uttered another of his frightened whimpers, and said: “Ole Grimsby’ll beat the daylights out of me! Lemme go!”

“He shan’t lay a finger on you!” promised Arabella, her cheeks flushed, and her eyes sparkling through, the tears they held.

The urchin came to the conclusion that she was soft in her head. “Ho!” he remarked bitterly, “youdon’ know ole Grimsby! Nor you don’ know his ole woman! Broke one of me ribs he did, onct!”

“He shall never do so again, my dear,” Arabella said, turning aside to pull open a drawer in one of the chests. She dragged out the soft shawl which had not so long since been swathed round the head of the sufferer from toothache, and put it round the boy, saying coaxingly: “There, let me wrap you up till we have had a fire lit! Is that more comfortable, my little man? Now sit down in this chair, and you shall have something to eat directly!”

He allowed himself to be lifted into the armchair, but his expression was so eloquent of suspicion and terror that it wrung Arabella’s tender heart She smoothed his cropped, sandy hair with one gentle hand, and said soothingly: “You must not be afraid of me: I promise you I will not hurt you, nor let your master either. What is your name, my dear?”

“Jemmy,” he replied, clutching the shawl about him, and fixing her with a frightened stare.

“And how old are you?”

This he was unable to answer, being uninstructed in the matter. She judged him to be perhaps seven or eight years old, but he was so undernourished that he might have been older. While she waited for the summons of the bell to bring her maid to the room, she put more questions to the child. He seemed to have no knowledge of the existence of any parents, volunteering that he was an orphing, on the Parish. When he saw that this seemed to distress her, he tried to comfort her by stating that one Mrs. Balham said he was love-begotten. It appeared that this lady had brought him up until the moment when he had passed into the hands of his present owner. An enquiry into Mrs. Balham’s disposition elicited the information that she was a rare one for jackey, and could half-murder anyone when under the influence of the stimulant. Arabella had no idea what jackey might be, but she gathered that Jemmy’s foster-mother was much addicted to strong drink. She questioned Jemmy more closely, and he, gaining confidence, imparted to her, in the most matter-of-fact way, some details of a climbing-boy’s life which drove the blood from her cheeks. He told her, with a certain distorted pride, of the violence of one of ole Grimsby’s associates, Mr. Molys, a master-sweep, who, only a year before, had been sentenced to two years imprisonment for causing the death of his six-year old slave.

“Two years!” cried Arabella, sickened by the tale of cruelty so casually unfolded. “If he had stolen a yard of silk from a mercer’s factory they would have deported him!”

Jemmy was not in a position to deny or to corroborate this statement, and preserved a wary silence. He saw that the young lady was very angry, and although her wrath did not seem to be directed against himself his experience had taught him to run no unnecessary risks of being suddenly knocked flying against the wall. He shrank into the corner of the chair therefore, and clutched the shawl more tightly round his person.

A discreet knock fell on the door, and a slightly flustered and considerably startled housemaid entered the room. “Was it you rang, miss?” she asked, in astonished accents. Then her eye alighted on Arabella’s visitor, and she uttered a genteel shriek. “Oh, miss! What a turn it gave me! The young varmint to give you such a fright! It’s the chimney-sweep’s boy, miss, and him looking for him all over! You come with me this instant, you wicked boy, you!”

Jemmy, recognizing a language he understood, whined that he had not meant to do it.

“Hush!” Arabella said, dropping her hand on one bony little shoulder. “I know very well it is the sweep’s boy, Maria, and if you look at him you will see how he has been used! Go downstairs, if you please, and fetch me some food for him directly—and send someone up to kindle the fire here!”

Maria stared at her as though she thought she had taken leave of her senses. “Miss!” she managed to ejaculate. “A dirty little climbing-boy?”

“When he has been bathed,” said Arabella quietly, “he will not be dirty. I shall need plenty of warm water, and the bath, if you please. But first a fire, and some milk and food for the poor child!”

The affronted handmaid bridled. “I hope, miss, you do not expect me to wash that nasty little creature! I’m sure I don’t know what her ladyship would say to such goings-on!”

“No,” said Arabella, “I expect nothing from you that I might expect from a girl with a more feeling heart than yours! Go and do what I have asked you to do, and desire Becky to come upstairs to me!”

“Becky?” gasped Maria.

“Yes, the girl who had the toothache. And when you have brought up food—some bread-and-butter, and some meat will do very well, but do not forget the milk!—you may send someone to tell Lord Bridlington that I wish to see him at once.”

Maria gulped, and stammered: “But, miss, his lordship is abed and asleep!”

“Well, let him be wakened!” said Arabella impatiently.

“Miss, I dare not for my life! His orders were no one wasn’t to disturb him till nine o’clock, and he won’t come, not till he has shaved himself, and dressed, not his lordship!”

Arabella considered the question, and finally came to the conclusion that it might be wiser to dispense with his lordship’s assistance for the time being. “Very well,” she said, “I will dress immediately, then, and see the sweep myself. Tell him to wait!”

“See the sweep—dress—Miss, you won’t never! With that boy watching you!” exclaimed the scandalized Maria.

“Don’t be such a fool, girl!” snapped Arabella, stamping her foot. “He’s scarcely older than my little brother at home! Go away before you put me out of all patience with you!”

This, however, Maria could not be persuaded to do until she had arranged a prim screen between the wondering Jemmy and his hostess. She then tottered away to spread the news through the house that Miss was raving mad, and likely to be taken off to Bedlam that very day. But since she did not dare to thwart a guest so much petted by her mistress, she delivered Arabella’s message to Becky, and condescended to carry up a tray of food to her room.

Jemmy, still huddled in the big chair, was bewildered by the unprecedented turn of events, and understood nothing of what was intended towards him. But he perfectly understood the significance of a plate of cold beef, and half a loaf of bread, and his sharp eyes glistened. Arabella, who had flung on her clothes at random, and done up her hair in a careless knot, settled him down to the enjoyment of his meal, and sallied forth to do battle with the redoubtable Mr. Grimsby, uneasily awaiting her in the front hall.

The scene, conducted under the open-mouthed stare of a footman in his shirt-sleeves, two astonished and giggling maids, and the kitchen-boy, was worthy of a better audience. Mr. Beaumaris, for instance, would have enjoyed it immensely. Mr. Grimsby, knowing that the sympathies of those members of the household he had so far encountered were with him, and seeing that his assailant was only a chit of a girl, tried at the outset to take a high line, rapidly cataloguing Jemmy’s many vices, and adjuring Arabella not to believe a word the varmint uttered. He soon discovered that what Arabella lacked in inches she more than made up for in spirit. She tore his character to shreds, and warned him of his ultimate fate; she flung Jemmy’s burns and bruises in his face, and bade him answer her if he dared. He did not dare. She assured him that never would she permit Jemmy to go back to him, and when he tried to point out his undoubted rights over the boy she looked so fierce that he backed before her. She said that if he wished to talk of his rights he might do so before a magistrate, and at these ominous words all vestige of fight went out of him. The misfortune which had overtaken his friend, Mr. Molys, was still fresh in his mind, and he desired to have no dealings with an unjust Law. There was no doubt that a young lady living in a house of this style would have those at her back who could, if she urged them to it, make things very unpleasant for a poor chimney-sweep. The course for a prudent man to follow was retreat: climbing-boys were easily come by, and Jemmy had never been a success. Mr. Grimsby, his back bent nearly double, edged himself out of the house, trying to assure Arabella in one breath that she might keep Jemmy and welcome, and that, whatever the ungrateful brat might say, he had been like a father to him.

Flushed with her triumph, Arabella returned to her room, where she found Jemmy, the plate of meat long since disposed of, eyeing with a good deal of apprehension the preparations for his ablutions. A capacious hip-bath stood before the fire, into which Becky was emptying the last of three large brass cans of hot water. Whatever Becky might think of climbing-boys, she had conceived a slavish adoration of Arabella, and she declared her willingness to do anything Miss might require of her.

“First,” said Arabella briskly, “I must wash him, and put basilicum ointment on his poor little feet and legs. Then I must get him some clothes to wear. Becky, do you know where to procure suitable clothes for a child in London?”

Becky nodded vigorously, twisting her apron between her fingers. She ventured to say that she had sent home a suit for her brother Ben which Mother had been ever so pleased with.

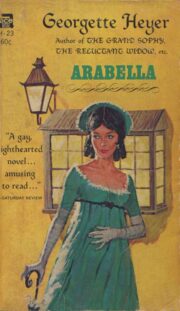

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.