“That style you have of tying your cravat!” said Sir Geoffrey. “I don’t perfectly recognize it. Is it something new? Should you object to telling me what you call it?”

“Not in the least,” replied Mr. Beaumaris blandly. “I call it Variation on an Original Theme.”

VIII

Mr. Beaumaris’s sudden realization that the little Tallant was no fool underwent no modification during the following days. It began to be borne in upon him, that charm her ever so wisely, she was never within danger of losing her head over him. She treated him in the friendliest fashion, accepted his homage, and—he suspected—was bent upon making the fullest use of him. If he paid her compliments, she listened to them with the most innocent air in the world but with a look in her candid gaze which gave him pause. The little Tallant valued his compliments not at all. Instead of being thrown into a flutter by the attentions of the biggest matrimonial prize in London, she plainly considered herself to be taking part in an agreeable game. If he flirted with her, she would generally respond in kind, but with so much the manner of one willing to indulge him that the hunter woke in him, and he was quite as much piqued as amused. He began to toy with the notion of making her fall in love with him in good earnest, just to teach her that the Nonpareil was not to be so treated with impunity. Once, when she was apparently not in the humour for gallantry, she actually had the effrontery to cut him short, saying: “Oh, never mind that! Who was that odd-looking man who waved to you just now? Why does he walk in that ridiculous way, and screw uphis mouth so? Is he in pain?”

He was taken aback, for really he had paid her a compliment calculated to cast her into exquisite confusion. His lips twitched, for lie had as few illusions about himself as had, to all appearances the lady beside him. “That,” he replied, “is Golden Ball, Miss Tallant, one of our dandies, as no doubt you have been told. He is not in pain. That walk denotes his consequence.”

“Good gracious! He looks as though he went upon stilts! Why does he think himself of such consequence?”

“He has never accustomed himself to the thought that he is worth not a penny less than forty thousand pounds a year,” replied Mr. Beaumaris gravely.

“What an odious person he must be!” she said scornfully. “To be consequential for such a reason as that is what I have no patience with!”

“Naturally you have not,” he agreed smoothly.

Her colour rushed up. She said quickly: “Fortune cannot make the man: I am persuaded you agree with me, for they tell me you are even more wealthy, Mr. Beaumaris, and I will say this!—you do not give yourself such airs as that!”

“Thank you,” said Mr. Beaumaris meekly. “I scarcely dared to hope to earn so great an encomium from you, ma’am.”

“Was it rude of me to say it? I beg your pardon!”

“Not at all.” He glanced down at her. “Tell me, Miss Tallant!—Just why do you grant me the pleasure of driving you out in my curricle?”

She responded with perfect composure, but with that sparkle in her eye which he had encountered several times before: “You must know that it does me a great deal of good socially to be seen in your company, sir!”

He was so much surprised that momentarily he let his hands drop. The grays broke into a canter, and Miss Tallant kindly advised him to mind his horses. The most notable whip in the country thanked her for her reminder, and steadied his pair. Miss Tallant consoled him for the chagrin he might have been supposed to feel by saying that she thought he drove very well. After a stunned moment, laughter welled up within him. His voice shook perceptibly as he answered: “You are too good, Miss Tallant!”

“Oh, no!” she said politely. “Shall you be at the masquerade at the Argyll Rooms tonight?”

“I never attend such affairs, ma’am!” he retorted, putting her in her place.

“Oh, then I shall not see you there!” remarked Miss Tallant, with unimpaired cheerfulness.

She did not see him there, but, little though she might have known it, he was obliged to exercise considerable restraint not to cast to the four winds his famed fastidiousness, and to minister to her vanity by appearing at the ball. He did not do it, and hoped that she had missed him. She had, but this was something she would not acknowledge even to herself. Arabella, who had liked the Nonpareil on sight, was setting a strong guard over her sensibilities. He had seemed to her, when first her eyes had alighted on his handsome person, to be almost the embodiment of a dream. Then he had uttered such words to his friend as must shatter for ever her esteem, and had wickedly led her into vulgar prevarication. Now it pleased his fancy to single her out from all the beauties in town, for reasons better known to himself than to her, but which she darkly suspected to be mischievous. No fool, the little Tallant! Not for one moment would she permit herself to indulge the absurd fancy that his court was serious. He might intrude into her meditations, but whenever she was aware of his having done so she was resolute in banishing his image. Sometimes she was strongly of the opinion that he had not believed a word of her boasts on that never to be sufficiently regretted evening in Leicestershire; at others, it seemed as though she had deceived him as completely as she had deceived Lord Fleetwood. It was impossible to fathom the intricacies of his mind, but one thing was certain: the great Mr. Beaumaris and the Vicar of Heythram’s daughter could have nothing to do with one another, so that the less the Vicar’s daughter thought about him the better it would be for her. One could not deny his address, or his handsome face, but one could—and one did—dwell on the many imperfections of his character. He was demonstrably indolent, a spoilt darling of society, with no thought for anything but his fleeting pleasure: a heartless, heedless leader of fashion, given over to selfishness, and every other vice which Papa’s daughter had been taught to think reprehensible.

If she missed him at the masquerade, no one would have guessed it. She danced indefatigably the whole night through, refused an offer of marriage from a slightly intoxicated Mr. Epworth, tumbled into bed at an advanced hour in the morning, and dropped instantly into untroubled sleep.

She was awakened at a most unseasonable hour by the sudden clatter of fire-irons in the cold hearth. Since the menial who crept into her chamber each morning to sweep the grate, and kindle a new fire there, performed her task with trained stealth, this noise was unusual enough to rouse Arabella with a start. A gasp and a whimper, proceeding from the direction of the fireplace, made her sit up with a jerk, blinking at the unexpected vision of a small, dirty, and tearstained little boy, almost cowering on the hearth-rug, and regarding her out of scared, dilating eyes.

“Good gracious!” gasped Arabella, staring at him. “Who are you?”

The child cringed at the sound of her voice, and returned no answer. The mists of sleep curled away from Arabella’s brain; her eyes took in the soot lying on the floor, the grimed appearance of her strange visitant, and enlightenment dawned on her. “You must be a climbing-boy!” she exclaimed. “But what are you doing in my room?” Then she perceived the terror in the pinched, and grimed small face, and she said quickly: “Don’t be afraid! Did you lose your way in those horrid chimneys?”

The urchin nodded, knuckling his eyes. He further volunteered the information that ole Grimsby would bash him for it. Arabella, who had had leisure to observe that one side of his face was swollen and discoloured, demanded: “Is that your master? Does he beat you?”

The urchin nodded again, and shivered.

“Well, he shan’t beat you for this!” said Arabella, stretching out her hand for the dressing-gown that was chastely disposed across the chair beside her bed. “Wait! I am going to get up!”

The urchin looked very much alarmed by this intelligence, and shrank back against the wall, watching her defensively. She slid out of bed, thrust her feet into her slippers, fastened her dressing-gown, and advanced kindly upon her visitor. He flung up an instinctive arm, cringing before her. He was clad in disgraceful rags, and Arabella now saw that the ends of his frieze nether-garments were much charred, and that his skinny legs and his bare feet were badly burnt. She dropped to her knees, crying out pitifully: “Oh, poor little fellow! You have burnt yourself so dreadfully!”

He slightly lowered his protective arm, looking suspiciously at her over it. “Ole Grimsby done it,” he said.

She caught her breath. “What!”

I’m afeared of going up the chimbley,” explained the urchin. “Sometimes there’s rats—big, fierce ’uns!”

She shuddered. “And he forces you to do so—like that?”

“They most of ’em does,” said the urchin, accepting life as he found it.

She held out her hand. “Let me see! I will not hurt you.” He looked wary, but after a moment appeared to consider that she might be speaking the truth, for he allowed her to take one of his feet in her hand. He was surprised when he saw that tears stood in her eyes, for in his experience the gentler sex was more apt to beat one with a broom-handle than to weep over one.

“Poor child, poor child!” Arabella said, a break in her voice. “You are so thin, too! I am sure you are half-starved! Are you hungry?”

“I’m allus hungry,” he replied simply.

“And cold too!” she said. “No wonder, in those rags! It is wicked, wicked!” She jumped up, and, grasping the bell pull that hung beside the fireplace, tugged it violently.

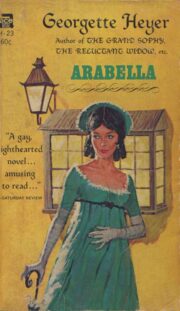

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.