Arabella had not been the reigning belle for twenty miles round Heythram without learning to distinguish between the flirt and the man who was in earnest, and she replied instantly: “I know very well that Mr. Beaumaris means nothing by his compliments. Indeed, I am in no danger of being taken-in like a goose!”

“Well, my love, I hope you are not!”

“You may be sure I am not. If you do not see any objection, ma’am, I mean to encourage Mr. Beaumaris’s attentions, and make the best use I may of them! He believes himself to be amusing himself at my expense; I mean to turn him to very good account! But as for losing my heart—No, indeed!”

“Mind, we cannot depend upon his continuing to single you out!” said Lady Bridlington, with unwonted caution. “If he did, it would be beyond anything great, but there is no saying, after all! However, last night’s work was enough to launch you, my dear, and I am deeply thankful!” She heaved an ecstatic sigh. “You will be invited everywhere, I daresay!”

She was quite right. Within a fortnight, she was in the happy position of finding herself with five engagements for the same evening, and Arabella had had to break into Sir John’s fifty-pound bill to replenish her wardrobe. She had been seen at the fashionable hour of the Promenade in the Park, sitting beside the Nonpareil, in his high-perch phaeton; she had been almost mobbed at the theatre; she was on nodding terms with all manner of exalted persons; she had received two proposals of marriage; Lord Fleetwood, Mr. Warkworth, Mr. Epworth, Sir Geoffrey Morecambe, and Mr. Alfred Somercote (to mention only the most notable of her suitors) had all entered the lists against Mr. Beaumaris; and Lord Bridlington, travelling by fast post all the way, had returned from the Continent to discover what his mother meant by filling his house with unknown females in his absence.

He expressed himself, in measured terms, as being most dissatisfied with Lady Bridlington’s explanation. He was a stocky, somewhat ponderous young man, with more sobriety than properly belonged to his twenty-six years. His understanding was not powerful, but he was bookish, and had early formed the habit of acquiring information by the perusal of authoritative tomes, so that by the time he had attained his present age his retentive memory was stocked with a quantity of facts which he was perhaps a little too ready to impart to his less well-read contemporaries. His father’s death, while he was still at Eton, coupled with a conviction that his mother stood in constant need of superior male guidance, had added disastrously to his self-consequence. He prided himself on his judgment; was a careful steward of his fortune; had the greatest dislike of anything bordering on the unusual; and deplored the frivolity of those who might have been expected to have been his cronies. His mother’s elation at not having spent one evening at home in ten days found no echo in his heart. He could neither understand why she should want to waste her time at social functions, nor why she should have been foolish enough to have invited a giddy girl to stay with her. He was afraid that the cost of all this mummery would be shocking; had Lady Bridlington asked for his counsel, which she might easily have done, he would have advised most strongly against Arabella’s visit.

Lady Bridlington was a trifle cast-down by this severity, but since her late husband had left her to the enjoyment of a handsome jointure, out of which she always shared the expenses of the house in Park Street with Frederick, she was able to point out to him that the charge of entertaining Arabella fell upon her, and not upon him. He said that the wish to dictate to his Mama was far from him, but that he must persist in thinking the affair most ill-advised. Lady Bridlington was fond of her only son, but Arabella’s success had quite gone to her head, and she was in no mood to listen to sober counsels. She retorted that he was talking a great deal of nonsense; upon which he bowed, compressed his lips, and bade her afterwards remember his words. He added that he washed his hands of the whole business. Lady Bridlington, who had no desire to see him fall a victim to Arabella’s charms, was torn between exasperation, and relief that he showed no sign of succumbing to them.

“I will allow her to be a pretty-enough young female,” said Frederick fairmindedly, “but there is a levity in her bearing which I cannot like, and all this gadding-about which she has led you into is not at all to my taste.”

“Well, I can’t conceive why you should have come running home in this foolish way!” retorted his mother.

“I thought it my duty, ma’am,” said Frederick.

“It is a great piece of folly, and people will think it excessively odd in you! No one looked to see you in England again until July at the earliest!”

She was mistaken. No one thought it in the least odd of Lord Bridlington to have curtailed his tour. The opinion of society was pithily summed up by Mrs. Penkridge, who said that she had guessed all along that that scheming Bridlington woman meant to marry the heiress to her own son. “Anyone could have seen how it would be!” she declared, with her mirthless jangle of laughter. “Such odious hypocrisy, too. to hold to it that she did not expect to see Bridlington in England until the summer! Mark my words, Horace, they will be married before the season is over!”

“Good gad, ma’am, I don’t fear Bridlington’s rivalry!” said her nephew, affronted.

“Then you are a goose!” said Mrs. Penkridge. “Everything is in his favour! He is the possessor of an honoured name, and a title, which you may depend upon it the girl wants, and—what is a great deal to the point, let me tell you!—he has all the advantage of living in the same house, of being always at hand to minister to her wishes, squire her to parties, and—Oh, it puts me out of all patience!”

But Miss Tallant and Lord Bridlington, from the very moment of exchanging their first polite greetings, had conceived a mutual antipathy which was in no way mitigated by the necessity each was under to behave towards the other with complaisance and civility. Arabella would not for the fortune she was believed to possess have grieved her kind hostess by betraying dislike of her son; Frederick’s sense of propriety, which was extremely nice, forbade him to neglect the performance of any attention due to his mother’s guest. He could appreciate, and, indeed, since he had a provident mind, applaud Mrs. Tallant’s ambition to dispose of her daughters creditably; and since his own mother had undertaken the task of finding a husband for Arabella, he was prepared to lend his countenance to her schemes. What shocked and disturbed him profoundly was the discovery, within a week of his homecoming, that every gazetted fortune-hunter in London was dangling after Arabella.

“I am at a loss, ma’am, to guess what you can possibly have said to lead anyone to suppose that Miss Tallant is an heiress!” he announced.

Lady Bridlington, who had several times wondered much the same thing, replied uneasily: “I never said a word, Frederick! There is not the least reason why anyone should suppose such an absurdity! I own, I was a trifle surprised when—But she is a very pretty girl, you know, and Mr. Beaumaris took one of his fancies to her!”

“I have never been intimate with Beaumaris,” said Frederick. “I do not care for the set he leads, and must deplore his making any modest female the object of his gallantry. The influence he exerts, moreover, over persons whom I should have supposed to have had more—”

“Never mind that!” begged his mother hastily. “You told me yesterday, Frederick! You may think Beaumaris what you please, but even you will not deny that it lies in his power to bring whom he will into fashion!”

“Very likely, ma’am, but I have yet to learn that it lies in his power to prevail upon such men as Epworth, Morecambe, Carnaby, and—I must add!—Fleetwood, to offer marriage to a female with nothing but her face to recommend her!”

“Not Fleetwood!” protested Lady Bridlington feebly.

“Fleetwood!” repeated Frederick in an inexorable tone. “I do not mean to say that he is precisely hanging out for a rich wife, but that he cannot afford to marry a penniless girl is common knowledge. Yet his attentions towards Miss Tallant are more marked even than those of Horace Epworth. And this is not all! From hints dropped in my presence, from remarks actually made to me, I am persuaded that the greater part of our acquaintance believes her to be in the possession of a handsome fortune! I repeat, ma’am: what can you have said to have given rise to this folly?”

“But I didn’t!” cried poor Lady Bridlington almost tearfully. “Indeed, I took the greatest pains not to touch on the question of her expectations! It is false to call her penniless, because she is no such thing! With all those children, of course the Tallants can do very little for her upon her marriage, but when her father dies—and Sophia, too, for she has some money as well—”

“A thousand or so!” interrupted Frederick contemptuously. “I beg your pardon, ma’am, but nothing could be more plain to me than that something you have said—inadvertently, I daresay!—has done all this mischief. For mischief I must deem it! A pretty state of affairs it will be if we are to have the world saying—as it will say, once the truth is known!—that you have foisted an impostress upon society!”

This terrible forecast temporarily outweighed in Lady Bridlington’s mind the sense of strong injustice the rest of her son’s remarks had aroused. She turned quite pale, and exclaimed: “What is to be done?”

“You may rely upon me, ma’am, to do what is necessary,” replied Frederick. “Whenever the opportunity offers, I shall say that I have no notion how such a rumour came to be spread about.”

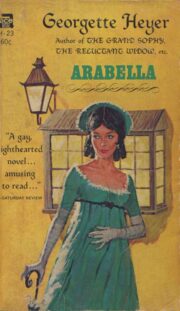

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.