“I have heard nothing of this! Who is she? Who told you she was charming?”

“Had it from Fleetwood last night, at the Great-Go,” explained Mr. Epworth negligently.

“That rattle! I wish you will not go so often to Watier’s, Horace! I warn you, it is useless to apply to me! I have not a guinea left in the world, and I dare not ask Mr. Penkridge to assist you again, until he has forgotten the last time!”

“Put me in the way of meeting this gal, and I’ll kiss my fingers to Penkridge, ma’am,” responded Mr. Epworth, gracefully suiting the action to the word. “Acquainted with Lady Bridlington, ain’t you? The gal’s staying with her.”

She stared at him. “If Arabella Bridlington had an heiress staying with her she would have boasted of it all over town!”

“No, she wouldn’t. Fleetwood particularly told me the gal don’t want it known. Don’t like being courted for her fortune. Pretty gal, too, by what Fleetwood says. Name of Tallant.”

“I never heard of a Tallant in my life!”

“Lord, ma’am, why should you? Keep telling you she comes from some dev’lish outlandish place in the north!”

“I would not set the least store by anything Fleetwood told me!”

“Oh, it ain’t him!” said Mr. Epworth cheerfully. “He don’t know the gal’s name either. It’s the Nonpareil. Knows all about the family. Vouches for the gal.”

Her expression changed: a still sharper look entered her eyes. She said quickly: “Beaumaris?” He nodded. “If he vouches for her—Is she presentable?”

He looked shocked, and answered in protesting accents:

“’Pon my soul, ma’am, you can’t be in your senses to ask me such a demned silly question! Now, I put it to you, would Beaumaris vouch for a gal that wasn’t slapup to the echo?”

“No. No, he would not,” she said decidedly. “If it’s true, and she has no vulgar connections, it would be the very thing for you, my dear Horace!”

“Just what I was thinking myself, ma’am,” said her nephew.

“I will pay Lady Bridlington a morning-visit,” said Mrs. Penkridge.

“That’s it: do the pretty!” Mr. Epworth encouraged her.

“It is tiresome, for I have never been upon intimate terms with her! However, this alters the circumstances! Leave it to me!”

Thus it was that Lady Bridlington found herself the object of Mrs. Penkridge’s attentions. Since she had never before been honoured with an invitation to one of that lady’s more exclusive parties, she was considerably elated, and at once seized the opportunity to invite Mrs. Penkridge to her own evening-party. Mrs. Penkridge accepted with another of her thin smiles, saying that she knew she could answer for her husband’s pleasure in attending the party, and departed, thinking out rapidly some form of engagement for him which would at once spare him an insipid evening, and render it necessary for her to claim her nephew’s escort.

VI

Lady Bridlington did not expect Arabella’s first party to be a failure, since she was a good hostess, and never offered her guests any but the best wines and refreshments, but that it should prove to be a wild success had not even entered her head. She had planned it more with the idea of bringing Arabella to the notice of other hostesses than as a brilliant social event; and although she had certainly invited a good many unattached gentlemen she had not held out the lure of dancing, or of cards, and so had little hope of seeing more than half of them in her spacious rooms. Her main preoccupation was lest Arabella should not be looking her best, or should jeopardize her future by some unconventional action, or some unlucky reference to that regrettable Yorkshire Vicarage. In general, the child behaved very prettily, but once or twice she had seriously alarmed her patroness, either by a remark which betrayed all too clearly the modesty of her circumstances—as when she had asked, in front of the butler, whether she should help to prepare the rooms for the party, for all the world as though she expected to be given an apron and a duster!—or by some impulsive action so odd as to be positively outrageous. Not readily would Lady Bridlington forget the scene outside the Soho Bazaar, when she and Arabella, emerging from this mart, found a heavy wagon stationary in the road, with the one scraggy horse between its shafts straining under an unsparing lash to set it in motion. At one instant a demure young lady had been at Lady Bridlington’s side; at the next a flaming fury was confronting the astonished wagoner, commanding him, with a stamp of one little foot to get down from the wagon at once—at once!—and not to dare to raise his whip again! He got down, quite bemused, and stood in front of the small fury, an ox of a man, towering above her while she berated him. When he had recovered his wits he attempted to justify himself, but failed signally to pacify the lady. He was a cruel wretch, unfit to be in charge of a horse, and a dolt, besides, not to perceive that one of the wheels was jammed, and through his own bad driving, no doubt! He began to be angry, and to shout Arabella down, but by this time a couple of chairmen, abandoning their empty vehicle, came across the square, expressing, in strong Hibernian accents, their willingness to champion the lady, and their desire to know whether the wagoner wanted to have his cork drawn. Lady Bridlington, all this time, had stood frozen with horror in the doorway of the Bazaar, unable to think of anything else to do than to be thankful that none of her acquaintances was present to witness this shocking affair. Arabella told the chairmen briskly that she would have no fighting, bade the wagoner observe the obstruction against which one of his rear wheels was jammed, herself went to the horse’s head, and began to back him. The chairmen promptly lent their aid; Arabella addressed a short, pithy lecture to the wagoner on the folly and injustice of losing one’s temper with animals, and rejoined her godmother, saying calmly: “It is mostly ignorance, you know!”

And although she did, when shown the impropriety of her behaviour, say she was sorry to have made a scene in public, it was evident that she was not in the least penitent. She said that Papa would have told her it was her duty to interfere in such a cause.

But no representations could induce her to say she was sorry for her quite unbecoming conduct two days later, when she entered her bedchamber to find a very junior housemaid, with a swollen face, lighting the fire. It appeared that the girl had the toothache. Now, Lady Bridlington had no desire that any of her servants should suffer the agonies of toothache, and had she been asked she would unquestionably have said that at the first convenient moment the girl should be sent off to have the tooth drawn. The mistress of a large household naturally had a duty to oversee the general well-being of her staff. Indeed, some years previously, when inoculation against cow-pox had been all the rage, she had with her own hands inoculated all the servants at Bridlington, and most of the tenants on the estate. Nearly every great lady had done so: it had been the accepted order of the day. But to bid the sufferer seat herself in the armchair in the best guest-chamber, to give her an Indian silk shawl to wrap round her head; and to disturb one’s hostess during the sacred hour of her afternoon-nap by bursting in upon her with a demand for laudanum, was carrying benevolence to quite undesirable lengths. Lady Bridlington did her best to convey the sense of this to Arabella, but she spoke to deaf ears. “The poor girl is in the most dreadful pain, ma’am!”

“Nonsense, my love! You must not let yourself be imposed upon. Persons of her class always made a to-do about nothing. She had better have the tooth drawn tomorrow, if she can be spared from her work, and—”

“Dear madam, I assure you she is in no case to be toiling up and down all these stairs with coal-scuttles!” said Arabella earnestly. “She should take some drops of laudanum, and lie down on her bed.”

“Oh, very well!” said her ladyship, yielding to the stronger will. “But there is no occasion for you to be putting yourself into this state, my dear! And to be asking one of the under-housemaids to sit down in your bedroom, and giving her one of your best shawls—”

“No, no, I have only lent it to her!” Arabella said. “She is from the country, you know, ma’am, and I think the other servants have not used her as they ought. She was homesick, and so unhappy! And the toothache made it worse, of course. I do believe she wanted someone to be kind to her more than anything else! She has been telling me about her home, and her little sisters and brothers, and—”

“Arabella!” uttered Lady Bridlington. “Surely you have not been gossiping with the servants?” She saw her young guest stiffen, and added hastily: “You should never encourage persons of her sort to pour out the history of their lives into your ears. I expect you meant it for the best, my dear, but you have no notion how encroaching—”

“I hope, ma’am—indeed, I know!” said Arabella, her eyes very bright, and her small figure alarmingly rigid, “that not one of Papa’s children would pass by a fellow-creature in distress!”

It was fast being borne in upon Lady Bridlington that the Reverend Henry Tallant was not only a grave handicap to his daughter’s social advancement, but a growing menace to her own comfort. She was naturally unable to express this conviction to Arabella, so she sank back on her pillows, saying feebly: “Oh, very well, but if people were to hear of it they would think it excessively odd in you, my dear!”

Whatever anyone else might think, it soon became plain that the episode had given her ladyship’s upper servants the poorest idea of Arabella’s social standing. Her ladyship’s personal maid, a sharp-faced spinster who had grown to middle-age in her service, and bullied her without compunction, ventured to hint, while she was dressing her mistress’s hair that evening, that it was easy to see Miss was not accustomed to living in large and genteel households.

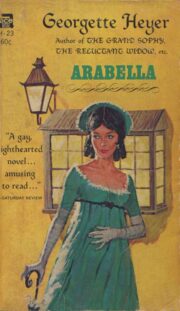

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.