“I am growing quite accustomed to London, and begin to know my way about the streets, though of course I do not walk out by myself yet. Lady Bridlington sends a footman with me, just as Bertram said she would, but I see that young females do go alone nowadays, only perhaps they are not of the haut ton. This is very important, and I am in constant dread that I shall do something improper, such as walking down St. James’s Street, where all the gentlemen’s clubs are, and very fast, which of course I do not wish to be thought. Lady Bridlington gives an evening-party, to introduce me to her friends. I shall be all of a quake, for everyone is so grand and fashionable, though perfectly civil, and much kinder than I had looked for. Sophy will like to know that Lord Fleetwood, whom I met on the road, as I wrote to you from Grantham, paid us a morning-visit, to see how I did, which was very amiable and obliging of him. Also Mr. Beaumaris, but we were out driving in the Park,. He left his card. Lady Bridlington was in transports, and has placed it above all the rest, which I think nonsensical, but I find that that is the way of the World, and makes me reflect on all Papa has said on the subject of Folly, and the Hollowness of Fashionable Life.” That seemed to dispose satisfactorily of Mr. Beaumaris. Arabella dipped her pen in the standish again. “Lady Bridlington is everything that is kind, and I am persuaded that Lord Bridlington is a very respectable young man, and not at all abandoned to the Pursuit of Pleasure, as Papa feared. His name is Frederick. He is traveling in Germany, and has visited a great many of the battlefields. He writes very interesting letters to his Mama, with which I am sure Papa would be pleased, for he seems to feel just as he ought, and moralizes on all lie sees in a truly elevating way, though rather long.” Arabella perceived that there was little room left on her sheet, and added in a cramped fist: “I would write more only that I cannot get a frank for this, and do not wish to put Papa to the expense of paying some sixpences for the second sheet. With my love to my brothers and sisters, and my affectionate duty to dear Papa, I remain your loving daughter Arabella.”

Plenty of promising matter there for Mama and the girls to pore over, and to discuss, even though so much remained unwritten! One could not resist boasting a very little about the compliments paid to one by a Royal Duke, or just mentioning that a fashionable peer of the realm had called to see how one did—not to mention the great Mr. Beaumaris, if one had happened to care a fig for that—but one felt quite shy of disclosing even to Mama how very gracious—how amazingly kind—everyone was being to an insignificant girl from Yorkshire.

For so it was. Shopping in Bond Street, driving on clement afternoons in Hyde Park, attending the service at the Chapel Royal, Lady Bridlington naturally encountered friends, and never failed to present Arabella to their notice. Some really forbidding dowagers who might have been expected to have paid scant heed to Arabella unbent in the most gratifying way, quite overpowering her by the kindness of their enquiries, and their insistence that Lady Bridlington should bring her to see them one day. Several introduced their daughters to Arabella, suggesting that she and they might walk in the Green Park some fine morning, so that in less than no time it seemed as though she had a host of acquaintances in London. The gentlemen were not more backward: it was quite a commonplace thing for some stroller in the Park to come up to Lady Bridlington’s barouche, and stand chatting to her, and to her pretty protégée; while more than one sprig of fashion, with whom her ladyship was barely acquainted, paid her a morning-visit on what seemed even to one so little given to speculation as Lady Bridlington the slenderest of excuses.

She was a little surprised, but after thinking about it for a few minutes she was as easily able to account for the ladies’ civility as the gentlemen’s. They were anxious to oblige her. This led her by natural stages to the reflection that she deserved a great deal of credit for having so well advertised Arabella’s visit to town. As for the gentlemen, she had never doubted, from the moment of setting eyes on her goddaughter, that that fairy figure and charming countenance could fail to attract instant admiration. Arabella had, moreover, the most enchanting smile, which brought dimples leaping to her cheeks, and was at once mischievous and appealing. Any but the most case-hardened of men, thought Lady Bridlington enviously, would be more than likely, under its intoxicating influence, to behave in a rash manner, however much he might afterwards regret it.

But none of these conclusions quite explained the morning-visits of several high-nosed ladies of fashion, whose civilities towards Lady Bridlington had hitherto consisted of invitations to their larger Assemblies, and bows exchanged from their respective carriages. Lady Somercote was particularly puzzling. She called in Park Street when Arabella was out walking with the three charming daughters of Sir James and Lady Hornsea, and she sat for over an hour with her gratified hostess. She expressed the greatest admiration of Arabella, whom she had met at the theatre with her godmother. “A delightful girl!” she said graciously. “Very pretty-behaved, and without the least hint of pretension in her dress or bearing!”

Lady Bridlington agreed to it, and since her mind did not move rapidly it was not until her guest was well into her next observation that she wondered why Arabella should be supposed to show pretension.

“Of good family, I apprehend?” said Lady Somercote, carelessly, but looking rather searchingly at her hostess.

“Of course!” replied Lady Bridlington, with dignity. “A most respected Yorkshire family!”

Lady Somercote nodded. “I thought as much. Excellent manners, and conducts herself with perfect propriety! I was particularly pleased with the modesty of her bearing: not the least sign of wishing to put herself forward! And her dress too! Just what I like to see in a young female! Nothing vulgar, such as one too often sees nowadays! When every miss out of the schoolroom is decked out with jewelry, it is refreshing to see one with a simple wreath of flowers in her hair. Somercote was much struck. Indeed, he quite took one of his fancies to her! You must bring her to Grosvenor Square next week, dear Lady Bridlington! Nothing formal, you know: a few friends only, and perhaps the young people may find themselves with enough couples to get up a little dance.”

She waited only for Lady Bridlington’s acceptance of this flattering invitation before taking her leave. Lady Bridlington was left with her mind in a whirl. She was shrewd enough to know that more than a compliment to herself must lie behind this unexpected honour, and was at a loss to discover the lady’s motive. She was the mother of five hopeful and expensive sons, and it was well known that the Somercote estates were heavily mortgaged. Advantageous marriages were a necessity to the Somercotes’ progeny, and no one was more purposeful in her pursuit of a likely heiress than their Mama. For a dismayed instant Lady Bridlington wondered whether, in her anxiety to assist Arabella, she had concealed her circumstances too well. But she could not recall that she had ever so much as mentioned them: indeed, her recollection was that she had taken care never to do so.

The Honourable Mrs. Penkridge, calling on her dear friend for the express purpose of bidding her and her protégée to a select Musical Soiree, and explaining, with apologies, how it was due to the stupidity of a secretary that her card of invitation had not reached her long since, spoke in even warmer terms of Arabella. “Charming! quite charming!” she declared, bestowing her frosted smile upon Lady Bridlington. “She will throw all our beauties into the shade! That simplicity is so particularly pleasing! You are to be congratulated!”

However perplexed Lady Bridlington might be by this speech, issuing, as it did, from the lips of one famed as much for her haughtiness as for her acid tongue, it seemed at least to dispose of the suspicion roused in her mind by Lady Somercote’s visit. The Penkridges were a childless couple. Lady Bridlington, on whom Mrs. Penkridge had more than once passed some contemptuous criticism, was not well-enough acquainted with her to know that almost the only sign of human emotion she had ever been seen to betray was her doting fondness for her nephew, Mr. Horace Epworth.

This elegant gentleman, complete to a point as regards side-whiskers, fobs, seals, quizzing-glass, and scented handkerchief, had lately honoured his aunt with one of his infrequent visits. Surprised and delighted, she had begged to know in what way she could be of service to him. Mr. Epworth had no hesitation in telling her. “You might put me in the way of meeting the new heiress, ma’am,” he said frankly. “Devilish fine gal—regular Croesus, too!”

She had pricked her ears at that, and exclaimed: “Whom can you be thinking of, my dear Horace? If you mean the Flint chit, I have it for a fact that—”

“Pooh! Nothing of the sort!” interrupted Mr. Epworth, waving the Flint chit away with one white and languid hand. “I daresay she has no more than thirty thousand pounds! This gal is so rich she puts ’em all in the shade. They call her the Lady Dives.”

“Who calls her so?” demanded his incredulous relative.

Mr. Epworth again waved his hand, this time in the direction which he vaguely judged to be northward. “Oh, up there somewhere, ma’am! Yorkshire, or some other of those dev’lish remote counties! Daresay she’s a merchant’s daughter: wool, or cotton, or some such thing. Pity, but I shan’t regard it; they tell me she’s charming!”

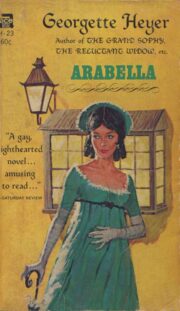

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.