“Oh, dear me, no!” said Arabella. “I have too often heard myself pointed out as the rich Miss Tallant to be under any illusion, sir! And it is for this reason that I wish to be quite unknown in London.”

Mr. Beaumaris smiled, but as the butler came in just then to announce dinner, he said nothing, but merely offered his arm to Arabella.

The dinner, which consisted of two courses, seemed to Arabella sumptuous beyond her wildest imaginings. No suspicion crossed her mind that her host, after one swift glance at his board, had resigned himself to the knowledge that the reputations of himself and his cook had been placed in jeopardy; or that that artist in the kitchen, having, with strange Gallic imprecations which made his various assistants quake, rent limb from limb two half-roasted Davenport fowls, and flung them into a pan with a bechamel sauce and some tarragons, was even now, as he arranged a basket of pastry on a dish, undecided whether to leave this dishonoured house on the instant, or to cut his throat with the larger carving-knife. Soup a la Reine was removed with fillets of turbot with an Italian sauce; and the chickens a la Tarragon were flanked by a dish of spinach and croutons, a glazed ham, two cold partridges, some broiled mushrooms, and a raised mutton pie. The second course presented Arabella with an even more bewildering choice, for there was, besides the baskets of pastry, a Rhenish cream, a jelly, a Savoy cake, a dish of salsify fried in butter, an omelette, and some anchovy toast. Mrs. Tallant had always prided herself on her housekeeping, but such a repast as this, embellished as it was by elegant garnitures, and subtle sauces, was quite beyond the range of the Vicarage cook. Arabella could not help opening her eyes a little at the array of viands spread before her, but she managed to conceal her awe, and to partake of what was offered to her with a very creditable assumption of unconsciousness. Mr. Beaumaris, perhaps loth to degrade his burgundy, or perhaps with a faint, despairing hope of adding piquancy to this commonplace meal, had instructed Brough to serve champagne. Arabella, having already cast discretion to the winds, allowed her glass to be filled, and sipped her way distastefully through it. It had a pleasantly exhilarating effect upon her. She informed Mr. Beaumaris that she was bound for the town residence of Lady Bridlington; created several uncles for the simple purpose of endowing herself with their fortunes; and at one blow disposed of four brothers and three sisters who might have been supposed to have laid a claim to a share of all this wealth. She contrived, without precisely making so vulgar a boast, to convey the impression that she was escaping from courtships so persistent as to amount to persecution; and Mr. Beaumaris, listening with intense pleasure, said that London was the very place for anyone desirous of escaping attention.

Arabella, embarking recklessly on her second glass of champagne, said that in a crowd one could more easily pass unnoticed than in the restricted society of the country.

“Very true,” agreed Mr. Beaumaris.

“You never did so!” remarked Lord Fleetwood, helping himself from the dish of mushrooms which Brough presented at his elbow. “You must know, ma’am, that you are in the presence of the Nonpareil—none other! quite the most noted figure in society since poor Brummell was done-up!”

“Indeed!” Arabella looked from him to Mr. Beaumaris with a pretty air of innocent enquiry. “I did not know—I might not have heard the name quite correctly, perhaps?”

“My dear Miss Tallant!” exclaimed his lordship, in mock horror. “Not know the great Beaumaris! the Arbiter of Fashion! Robert, you are quite set down!”

Mr. Beaumaris, whose almost imperceptibly lifted finger had brought the watchful Brough to his side, was murmuring some command into that attentive but astonished ear, and paid no heed. His command was passed on to the footman hovering by the side-table, who, being quite a young man, and as yet imperfectly in control of his emotions, betrayed in his startled look some measure of the incredulity which shook his trained soul. The coldly quelling eye of his superior recalled him speedily to a sense of his position, however, and he left the room to carry the stupefying command still farther.

Miss Tallant, meanwhile, had perceived an opportunity to gratify her most pressing desire, which was to snub her host beyond possibility of his recovery, “Arbiter of Fashion?” she said, in a blank voice. “You cannot, surely, mean one of the dandy-set? I had thought—Oh, I beg your pardon! I expect that in London that is quite as important as being a great soldier, or a statesman, or—or some such thing!”

Even Lord Fleetwood could scarcely mistake the tenor of this artless speech. He gave an audible gasp. Miss Blackburn, whose enjoyment of dinner had already been seriously impaired, refused the partridge, and tried unavailingly to catch her charge’s eye. Only Mr. Beaumaris, hugely enjoying himself, appeared unmoved. He replied coolly: “Oh, decidedly! One’s influence is so far-reaching!”

“Oh?” said Arabella politely.

“Why, certainly, ma’am! One may blight a whole career by the mere raising of an eyebrow, or elevate a social aspirant to the ranks of the highest ton only by leaning on his arm for the length of a street.”

Miss Tallant suspected that she was being quizzed, but the strange exhilaration had her in its grip, and she did not hesitate to cross swords with this expert fencer. “No doubt, sir, if I had ambitions to cut a figure in society your approval would be a necessity?”

Mr. Beaumaris, famed for his sword-play, slipped under her guard with an unexpected thrust. “My dear Miss Tallant, you need no passport to admit you to the ranks of the most sought-after! Even I could not depress the claims of one endowed with—may I say it?—your face, your figure, and your fortune!”

The colour flamed up into Arabella’s cheeks; she choked over the last of her wine, tried to look arch, and only succeeded in looking adorably confused. Lord Fleetwood, realizing that his friend had embarked on yet another of his practised flirtations, directed an indignant glance at him, and did his best to engage the heiress’s attention himself. He was succeeding quite well when he was thrown off his balance by the unprecedented behaviour of Brough, who, as the second course made its appearance, removed his champagne-glass, replacing it with a goblet, which he proceeded to fill with something out of a tall flagon which his lordship strongly suspected was iced lemonade. One sip was enough alike to confirm this hideous fear and to deprive his lordship momentarily of the power of speech. Mr. Beaumaris, blandly swallowing some of the innocuous mixture, seized the opportunity to re-engage Miss Tallant in conversation.

Arabella had been rather relieved to see her wine-glass removed, for although she would have died rather than have owned to it she thought the champagne decidedly nasty, besides making her want to sneeze. She took a revivifying draught of lemonade, glad to discover that in really fashionable circles this mild beverage was apparently served with the second course. Miss Blackburn, better versed in the ways of the haut ton, now found herself unable to form a correct judgment of her host. To be plunged from a conviction that he was truly gentlemanlike to a shocked realization that he was nothing but a coxcomb, and then back again, quite overset the poor little lady. She knew not what to think, but could not forbear casting him a glance eloquent of the warmest gratitude. His eyes encountered hers, but for such a fleeting instant that she could never afterwards be sure whether she had caught the glimmer of an amused smile in them, or whether she had imagined it.

Brough, receiving a message at the door, announced that madam’s groom had brought a hired coach to the house, and desired to know when she would wish to resume her journey to Grantham.

“It can wait,” said Mr. Beaumaris, replenishing Arabella’s glass. “A little of the Rhenish cream, Miss Tallant?”

“How long,” demanded Arabella, recalling Mr. Beaumaris’s odious words to his friend, “will it take them to mend my own carriage?”

“I understand, miss, that a new pole will be needed. I could not say how long it will be.”

A faint clucking from Miss Blackburn indicated dismay at this intelligence. Mr. Beaumaris said: “A tiresome accident, but I beg you will not distress yourselves! I will send my chaise to pick you up in Grantham at whatever hour tomorrow should be agreeable to you.”

Arabella thanked him, but was resolute in refusing his offer, for which, she assured him, there was not the slightest occasion. If the wheelwright proved too dilatory for her patience she would finish her journey by post. “It will be quite an experience!” she declared truthfully. “My friends assure me that I am a great deal too old-fashioned in my notions—that quite a respectable degree of comfort is to be found in hired chaises!”

‘“I perceive,” said Mr. Beaumaris, “that we have much in common, ma’am. But I shall not allow a distaste for hired vehicles to be old-fashioned. Let us rather say that we have a little more nicety than the general run of our fellow-creatures!” He turned his head towards the butler. “Let a message be conveyed to the wheelwright, Brough, that he will oblige me by repairing Miss Tallant’s carriage with all possible expedition.”

Miss Tallant had nothing to do but thank him for his kind offices, and finish her Rhenish cream. That done, she rose from the table, saying that she had trespassed too long on her host’s hospitality, and must now take her leave of him, with renewed thanks for his kindness.

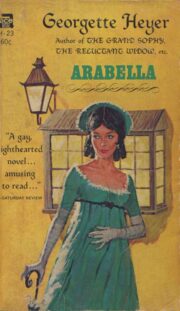

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.