Lord Fleetwood, meanwhile, had ensconced himself beside Arabella, and was chatting to her in his inconsequent, cheerful way, which set her quite at ease. He was delighted to hear that she was on her way to London, hoped to have the pleasure of meeting her there—in the Park, possibly, or at Almack’s. He had plenty of anecdotes of ton with which to entertain her, and rattled on in an agreeable fashion until the housekeeper came to escort the ladies upstairs.

They were taken to a guest-chamber on the first floor, and handed over there to a housemaid, who brought up hot water for them, and bore their damp coats away to be dried in the kitchen.

“Everything in the first style of elegance!” breathed Miss Blackburn. “But we should not be dining here! I feel sure we ought not, my dear Miss Tallant!”

Arabella was a little doubtful on this score herself, but as it was now too late to draw back she stifled her misgivings, and said stoutly that she was persuaded there could be no objection. Finding a brush and comb laid out on the dressing-table, she began to tidy her rather tumbled locks.

“They are most gentlemanlike,” said Miss Blackburn, deriving comfort from this circumstance. “Of the first rank of fashion, I daresay. They will be here for the hunting, depend upon it: I collect this is a hunting-box,”

“A hunting-box!” exclaimed Arabella, awed. “Is it not very large and grand, ma’am, to be that?”

“Oh, no, my dear! Quite a small house! The Tewkesburys, whose sweet children I was engaged to instruct before I removed to Mrs. Caterham’s establishment, had one much larger, I assure you. This is the Melton country, you must know.”

“Good heavens, are they Melton men, then? Oh, how much I wish Bertram could be here! What I shall have to tell him! I think it is Mr. Beaumaris who owns the house: I wonder who the other is? I thought when I first saw him he could not be quite the thing, for that striped waistcoat, you know, and that spotted handkerchief he wears instead of a cravat makes him look like a groom, or some such thing. But when he spoke, of course I knew he was not a vulgar person at all.”

Miss Blackburn, feeling for once in her life pleasantly superior, gave a titter of laughter, and said pityingly: “Oh, dear me no, Miss Tallant! You will find a great many young gentleman of fashion wearing much odder clothes than that! It is what Mr. Geoffrey Tewkesbury—a very modish young man!—used to call all the crack!” She added pensively: “But I must confess that I do not care for it myself, and nor did dear Mrs. Tewkesbury. My notion of a true gentleman is someone like Mr. Beaumaris!”

Arabella dragged the comb ruthlessly through a tangle. “I thought him a very proud, reserved man!” she declared. “And not at all hospitable!” she added.

“Oh, no, how can you say so? How very kind and obliging it was of him to place me in the best place, so near the fire! Delightful manners! nothing high in them at all! I was quite overcome by his condescension!”

It was evident to Arabella that she and Miss Blackburn regarded their host through two very different pairs of spectacles. She preserved an unconvinced silence, and as soon as Miss Blackburn had finished prinking her crimped gray locks at the mirror, suggested that they should go downstairs again. Accordingly they left the room, and crossed the upper hall to the head of the stairway. Mr. Beaumaris’s fancy had led him to carpet his stairs, a luxury which Miss Blackburn indicated to her charge with one pointing finger and a most expressive glance.

Across the lower hall, the door into the library stood ajar. Lord Fleetwood’s voice, speaking in rallying tones, assailed the ladies’ ears. “I swear you are incorrigible!” said his lordship. The loveliest of creatures drops into your lap, like a veritable honey-fall, and you behave as though a gull-groper had forced his way into your house!”

Mr. Beaumaris replied with disastrous clarity: “My dear Charles, when you have been hunted by every trick known to the ingenuity of the female mind, you may more readily partake of my sentiments upon this occasion! I have had beauties hopeful of wedding my fortune swoon in my arms, break their bootlaces outside my London house, sprain their ankles when my arm is there to support them, and now it appears that I am to be pursued even into Leicestershire! An accident to her coach! Famous! What a greenhorn she must believe me to be!”

A small hand closed like a vice about Miss Blackburn’s wrist. Herself bridling indignantly, she saw Arabella’s eyes sparkling, and her cheeks most becomingly flushed. Had she been better acquainted with Miss Tallant she might have taken fright at these signs. Arabella breathed into her ear: “Miss Blackburn, can I trust you?”

Miss Blackburn would have vigorously assured her that she could, but the hand released her wrist, and flew up to cover her mouth. Slightly startled, she nodded. To her amazement, Arabella then picked up her skirts, and fled lightly back to the top of the stairs. Turning there, she began to come slowly down again, saying in a clear, carrying voice:—“Yes, indeed! I am sure I have said the same, dear ma’am, times out of mind! But do, pray, go before me!”

Miss Blackburn, turning to stare at her, with her mouth at half-cock, found a firm young hand in the small of her back, and was thrust irresistibly onward.

“But in spite of all,” said Arabella, “I prefer to travel with my own horses!”

The awful scowl that accompanied these light words quite bewildered the poor little governess, but she understood that she was expected to reply in kind, and said in a quavering voice: “Very true, my dear!”

The scowl gave place to an encouraging smile. Any one of Arabella’s brothers or sisters would have begged her at this point to consider all the consequences of impetuosity; Miss Blackburn, unaware of the eldest Miss Tallant’s besetting fault, was merely glad that she had not disappointed her. Arabella tripped across the hall to that half-open door, and entered the library again.

It was Lord Fleetwood who came forward to receive her. He eyed her with undisguised appreciation, and said: “Now you will be more comfortable! Devillish dangerous to sit about in a wet coat, y’know! But we are yet unacquainted, ma’am! The stupidest thing—never can catch a name when it is spoken! That man of Beaumaris’s mumbles so that no one can hear him! You must let me make myself known to you, too—Lord Fleetwood, very much at your service!”

“I,” said Arabella, a most dangerous glitter in her eye, “am Miss Tallant!”

His lordship, murmuring polite gratification at being made the recipient of this information, was surprised to find his inanities quite misunderstood. Arabella fetched a world-weary sigh, and enunciated with a scornful curl of her lip: “Oh, yes! The Miss Tallant!”

“Th-the Miss Tallant?” stammered his lordship, all at sea.

“The rich Miss Tallant!” said Arabella.

His lordship rolled an anguished and an enquiring eye at his host, but Mr. Beaumaris was not looking at him. Mr. Beaumaris, his attention arrested, was regarding the rich Miss Tallant with a distinct gleam of curiosity, not unmixed with amusement, in his face.

“I had hoped that here at least I might be unknown!” said Arabella, seating herself in a chair a little withdrawn from the fire. “Ah, you must let me make you known to Miss Blackburn, my—my dame de compagnie!”

Lord Fleetwood sketched a bow; Miss Blackburn, her countenance wooden, dropped him a slight curtsy, and sat down on the nearest chair.

“Miss Tallant,” repeated Lord Fleetwood, searching his memory in vain for enlightenment “Ah, yes! Of course! Er—I don’t think I have ever had the honour of meeting you in town, have I, ma’am?”

Arabella directed an innocent look from him to Mr. Beaumaris, and back again, and clapped her hands together with an assumption of mingled delight and dismay. “Oh, you did not know!” she exclaimed. “I need never have told you! But when you looked so, I made sure you were as bad as all the rest! Was anything ever so vexatious? I most particularly desire to be quite unknown in London!”

“My dear ma’am, you may rely on me!” promptly replied his lordship, who, hike most rattles, thought himself the model of discretion. “And Mr. Beaumaris, you know, is in the same case as yourself, and able to sympathize with you!”

Arabella glanced at her host, and found that he had raised his quizzing-glass, which hung round his neck on a long black riband, and was surveying her through it. She put up her chin a little, for she was by no means sure that she cared for this scrutiny. “Indeed?” she said.

It was not the practice of young ladies to put up their chins in just that style if Mr. Beaumaris levelled his glass at them: they were more in the habit of simpering, or of trying to appear unconscious of his regard. But Mr. Beaumaris saw that there was a decidedly militant sparkle in this lady’s eye, and his interest, at first tickled, was now fairly caught. He let his glass fall, and said gravely: “Indeed! And you?”

“Alas!” said Arabella, “I am fabulously wealthy! It is the greatest mortification to me! You can have no notion!”

His lips twitched. “I have always found, however, that a large fortune carries with it certain advantages.”

“Oh, you are a man! I shall not allow you to know anything of the matter!” she cried. “You cannot know what it means to be the object of every fortune-hunter, courted and odiously flattered only for your wealth, until you are ready to wish that you had not a penny in the world!”

Miss Blackburn, who had hitherto supposed her charge to be a modest, well-behaved girl, barely repressed a shudder. Mr. Beaumaris, however, said: “I feel sure that you underrate yourself, ma’am.”

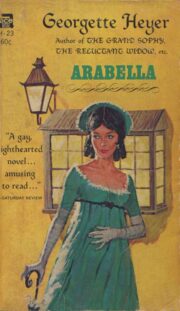

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.