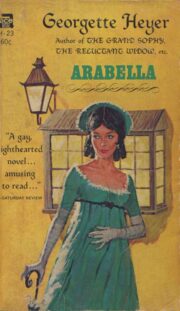

Georgette Heyer

Arabella

I

The schoolroom in the Parsonage at Heythram was not a large apartment, but on a bleak January day, in a household where the consumption of coals was a consideration, this was not felt by its occupants to be a disadvantage. Quite a modest fire in the high, barred grate made it unnecessary for all but one of the four young ladies present to huddle shawls round their shoulders. But Elizabeth, the youngest of the Reverend Henry Tallant’s handsome daughters, was suffering from the ear-ache, and, besides stuffing a roasted onion into the afflicted orifice, had swathed her head and neck in an old Cashmere shawl. She lay curled up on an aged sofa, with her head on a worn red cushion, and from time to time uttered a long-suffering sigh, to which none of her sisters paid any heed. Betsy was known to be sickly. It was thought that the climate of Yorkshire did not agree with her constitution, and since she spent the greater part of the winter suffering from a variety of minor ills her delicacy was regarded by all but her Mama as a commonplace.

There were abundant signs, littered over the table in the centre of the room, that the young ladies had retired to this cosy, shabby apartment to hem shirts, but only one of them, the eldest, was thus engaged. In a chair on one side of the fireplace, Miss Margaret Tallant, a buxom fifteen-year old, was devouring the serial story in a bound volume of The Ladies’ Monthly Museum, with her fingers stuffed in her ears, and seated opposite to Miss Arabella, her stitchery lying neglected on the table before, sat Miss Sophia, reading aloud from another volume of this instructive periodical.

“I must say, Bella,” she remarked, momentarily lowering the book, “I find this most perplexing! Only listen to what it says here! We have presented our subscribers with fashions of the newest pattern, not such as shall violate the law of propriety and decorum, but such as shall assist the smile of good humour, and give an additional charm to the carriage of benevolence. Economy ought to be the order of the day—And then, if you please, there is a picture of the most ravishing evening-gown—Do but look at it, Bella!—and it says that the Russian bodice is of blue satin, fastened in front with diamonds! Well!”

Her sister obediently raised her eyes from the wristband she was hemming, and critically scanned the willowy giantess depicted amongst the Fashion Notes. Then she sighed, and once more bent her dark head over her work. “Well, if that is their notion of economy, I am sure I couldn’t go to London, even if my godmother invited me. And I know she won’t,” she said fatalistically.

“You must and you shall go!” declared Sophy, in accents of strong resolution. “Only think what it may mean to all of us if you do!”

“Yes, but I won’t go looking like a dowd,” objected Arabella, “and if I am obliged to have diamond fastenings to my bodice, you know very well—”

“Oh, stuff! I daresay that is the extreme of fashion, or perhaps they are made of paste! And in any event this is one of the older numbers. I know I saw in one of them that jewelry is no longer worn in the mornings, so very likely—Where is that volume? Margaret, you have it! Do, pray, give it to me! You are by far too young to be interested in such things!”

Margaret uncorked her ears to snatch the book out of her sister’s reach. “No! I’m reading the serial story!”

“Well, you should not. You know Papa does not like us to read romances.”

“If it comes to that,” retorted Margaret, “he would be excessively grieved to find you reading nothing better than the latest modes!”

They looked at one another; Sophy’s lip quivered. “Dear Meg, do pray give it to me, only for a moment!”

“Well, I will when I have finished the Narrative of Augustus Waldstein,” said Margaret. “But only for a moment, mind!”

“Wait, I know there is something here to the purpose!” said Arabella, dropping her work to flick over the pages of the volume abandoned by Sophia. “Method of Preserving Milk by Horse-Radish ... White Wax for the Nails ... Human Teeth placed to Stumps .. Yes, here it is! Now, listen, Meg! Where a Female has in early life dedicated her attention to novel-reading she is unfit to become the companion of a man of sense, or to conduct a family with propriety and decorum. There!” She looked up, the prim pursing of her lips enchantingly belied by her dancing eyes.

“I am sure Mama is not unfit to be the companion of a man of sense!” cried Margaret indignantly. “And she reads novels! And even Papa does not find The Wanderer objectionable, or Mrs. Edgeworth’s Tales!”

“No, but he did not like it when he found Bella reading The Hungarian Brothers, or The Children of the Abbey,” said Sophia, seizing the opportunity to twitch The Ladies’ Monthly Museum out of her sister’s slackened grasp, “He said there was a great deal of nonsense in such books, and that the moral tone was sadly lacking.”

“Moral tone is not lacking in the serial I am reading!” declared Margaret, quite ruffled. “Look what it says there, near the bottom of the page! ‘Albert! be purity of character your duty?’ I am sure he could not dislike that!”

Arabella rubbed the tip of her nose. “Well, I think he would say it was fustian,” she remarked candidly. “But do give the book back to her, Sophy!”

“I will, when I have found what I’m looking for. Besides, it was I who had the happy notion to borrow the volumes from Mrs. Caterham, so—Yes, here it is! It says that only jewelry of very plain workmanship is worn in the mornings nowadays.” She added, on a note of doubt: “I daresay the fashions don’t change so very fast, even in London. This number is only three years old.”

The sufferer on the sofa sat up cautiously. “But Bella hasn’t got any jewelry, has she?”

This observation, delivered with all the bluntness natural in a damsel of only nine summers, threw a blight over the company.

“I have the gold locket and chain with the locks of Papa’s and Mama’s hair in it,” said Arabella defensively.

“If you had a tiara, and a—a cestus, and an armlet to match it, it might answer,” said Sophy. “There is a toilet described here with just those ornaments.”

Her three sisters gazed at her in astonishment. “What is a cestus?” they demanded.

Sophy shook her head. “I don’t know,” she confessed.

“Well, Bella hasn’t got one at all events,” said the Job’s comforter on the sofa.

“If she were so poor-spirited as to refuse to go to London for such a trifling reason as that, I would never forgive her!” declared Sophy.

“Of course I would not!” exclaimed Arabella scornfully. “But I have not the least expectation that Lady Bridlington will invite me, for why should she, only because I am her goddaughter? I never saw her in my life!”

“She sent a very handsome shawl for your christening gift,”said Margaret hopefully.

“Besides being Mama’s dearest friend,” added Sophy.

“But Mama has not seen her either—at least, not for years and years!”

“And she never sent Bella anything else, not even when she was confirmed,” pointed out Betsy, gingerly removing the onion from her ear, and throwing it into the fire.

“If your ear-ache is better,” said Sophia, eyeing her with disfavour, “you may hem this seam for me! I want to draw a pattern for a new flounce.”

“Mama said I was to sit quietly by the fire,” replied the invalid, disposing herself more comfortably. “Are there any acrostics in those fusty old books?”

“No, and if there were I would not give them to anyone so disobliging as you, Betsy!” said Sophy roundly.

Betsy began to cry, in an unconvincing way, but as Margaret was once more absorbed in her serial, and Arabella had drawn Sophia’s attention to the picture of a velvet pelisse trimmed lavishly with ermine, no one paid any heed to her, and she presently relapsed into silence, merely sniffing from time to time, and staring resentfully at her two eldest sisters.

They presented a charming picture, as they sat poring over their book, their dark ringlets intermingled, and their arms round each other’s waists. They were very plainly dressed, in gowns of blue kerseymere, made high to the throat, and with long tight sleeves; and they wore no other ornaments than a knot or two of ribbons; but the Vicar’s numerous offspring were all remarkable for their good looks and had very little need of embellishment. Although Arabella was unquestionably the Beauty of the family, it was pretty generally agreed in the neighbourhood that once Sophia had outgrown the over-plumpness of her sixteen years she might reasonably hope to rival her senior. Each had large, dark, and expressive eyes, little straight noses, and delicately moulded lips; each had complexions which were the envy of less fortunate young ladies, and which owed nothing to Denmark Lotion, Olympian Dew, Blood of Ninon, or any other aid to beauty advertised in the society journals. Sophia was the taller of the two; Arabella had by far the better figure, and the neater ankle. Sophia looked to be the more robust; Arabella enchanted her admirers by a deceptive air of fragility, which inspired one romantically-minded young gentleman to liken her to a leaf blown by the wind; and another to address a very bad set of verses to her, apostrophizing her as the New Titania. Unfortunately, Harry had found this effusion, and had shown it to Bertram, and until Papa had said, with his gentle austerity, that he considered the jest to be outworn, they had insisted on hailing their sister by this exquisitely humorous appellation.

"Arabella" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Arabella". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Arabella" друзьям в соцсетях.