I cross the road with a group of chattering students.They don’t notice me, but together we dodge the puddles. An automobile, small enough to be one of my brother’s toys, whizzes past and sprays a girl in glasses. She swears, and her friends tease her.

I drop behind.

The city is pearl gray.The overcast sky and the stone buildings emit the same cold elegance, but ahead of me, the Panthéon shimmers. Its massive dome and impressive columns rise up to crown the top of the neighborhood. Every time I see it, it’s difficult to pull away. It’s as if it were stolen from ancient Rome or, at the very least, Capitol Hill. Nothing I should be able to view from a classroom window.

I don’t know its purpose, but I assume someone will tell me soon.

My new neighborhood is the Latin Quarter, or the fifth arrondissement. According to my pocket dictionary, that means district, and the buildings in my arrondissement blend one into another, curving around corners with the sumptuousness of wedding cakes.The sidewalks are crowded with students and tourists, and they’re lined with identical benches and ornate lampposts, bushy trees ringed in metal grates, Gothic cathedrals and tiny crêperies, postcard racks, and curlicue wrought iron balconies.

If this were a vacation, I’m sure I’d be charmed. I’d buy an Eiffel Tower key chain, take pictures of the cobblestones, and order a platter of escargot. But I’m not on vacation. I am here to live, and I feel small.

The School of America’s main building is only a two-minute walk from Résidence Lambert, the junior and senior dormitory. The entrance is through a grand archway, set back in a courtyard with manicured trees. Geraniums and ivy trail down from window boxes on each floor, and majestic lion’s heads are carved into the center of the dark green doors, which are three times my height. On either side of the doors hangs a red, white, and blue flag—one American, the other French.

It looks like a film set. A Little Princess, if it took place in Paris. How can such a school really exist? And how is it possible that I’m enrolled? My father is insane to believe I belong here. I’m struggling to close my umbrella and nudge open one of the heavy wooden doors with my butt, when a preppy guy with faux-surfer hair barges past. He smacks into my umbrella and then shoots me the stink-eye as if: (1) it’s my fault he has the patience of a toddler and (2) he wasn’t already soaked from the rain.

Two-point deduction for Paris. Suck on that, Preppy Guy.

The ceiling on the first floor is impossibly high, dripping with chandeliers and frescoed with flirting nymphs and lusting satyrs. It smells faintly of orange cleaning products and dry-erase markers. I follow the squeak of rubber soles toward the cafeteria. Beneath our feet is a marbled mosaic of interlocking sparrows. Mounted on the wall, at the far end of the hall, is a gilded clock that’s chiming the hour.

The whole school is as intimidating as it is impressive. It should be reserved for students with personal bodyguards and Shetland ponies, not someone who buys the majority of her wardrobe at Target.

Even though I saw it on the school tour, the cafeteria stops me dead. I used to eat lunch in a converted gymnasium that reeked of bleach and jockstraps. It had long tables with preattached benches, and paper cups and plastic straws.The hairnetted ladies who ran the cash registers served frozen pizza and frozen fries and frozen nuggets, and the soda fountains and vending machines provided the rest of my so-called nourishment.

But this. This could be a restaurant.

Unlike the historic opulence of the hall, the cafeteria is sleek and modern. It’s packed with round birch tables and plants in hanging baskets. The walls are tangerine and lime, and there’s a dapper Frenchman in a white chef’s hat serving a variety of food that looks suspiciously fresh. There are several cases of bottled drinks, but instead of high-sugar, high-caf colas, they’re filled with juice and a dozen types of mineral water. There’s even a table set up for coffee. Coffee. I know some Starbucks-starved students at Clairemont who’d kill for in-school coffee.

The chairs are already filled with people gossiping with their friends over the shouting of the chefs and the clattering of the dishes (real china, not plastic). I stall in the doorway. Students brush past me, spiraling out in all directions. My chest squeezes. Should I find a table or should I find breakfast first? And how am I even supposed to order when the menu is in freaking French?

I’m startled when a voice calls out my name. Oh please oh please oh please . . .

A scan through the crowd reveals a five-ringed hand waving from across the room. Meredith points to an empty chair beside her, and I weave my way there, grateful and almost painfully relieved.

“I thought about knocking on your door so we could walk together, but I didn’t know if you were a late sleeper.” Meredith’s eyebrows pinch together with worry. “I’m sorry, I should have knocked.You look so lost.”

“Thanks for saving me a spot.” I set down my stuff and take a seat.There are two others at the table and, as promised the night before, they’re from the photograph on her mirror. I’m nervous again and readjust my backpack at my feet.

“This is Anna, the girl I was telling you about,” Meredith says.

A lanky guy with short hair and a long nose salutes me with his coffee cup. “Josh,” he says. “And Rashmi.” He nods to the girl next to him, who holds his other hand inside the front pocket of his hoodie. Rashmi has blue-framed glasses and thick black hair that hangs all the way down her back. She gives me only the barest of acknowledgments.

That’s okay. No big deal.

“Everyone’s here except for St. Clair.” Meredith cranes her neck around the cafeteria. “He’s usually running late.”

“Always,” Josh corrects. “Always running late.”

I clear my throat. “I think I met him last night. In the hallway.”

“Good hair and an English accent?” Meredith asks.

“Um.Yeah. I guess.” I try to keep my voice casual.

Josh smirks. “Everyone’s in luuurve with St. Clair.”

“Oh, shut up,” Meredith says.

“I’m not.” Rashmi looks at me for the first time, calculating whether or not I might fall in love with her own boyfriend.

He lets go of her hand and gives an exaggerated sigh. “Well, I am. I’m asking him to prom. This is our year, I just know it.”

“This school has a prom?” I ask.

“God no,” Rashmi says. “Yeah, Josh.You and St. Clair would look really cute in matching tuxes.”

“Tails.” The English accent makes Meredith and me jump in our seats. Hallway boy. Beautiful boy. His hair is damp from the rain. “I insist the tuxes have tails, or I’m giving your corsage to Steve Carver instead.”

“St. Clair!” Josh springs from his seat, and they give each other the classic two-thumps-on-the-back guy hug.

“No kiss? I’m crushed, mate.”

“Thought it might miff the ol’ ball and chain. She doesn’t know about us yet.”

“Whatever,” Rashmi says, but she’s smiling now. It’s a good look for her. She should utilize the corners of her mouth more often.

Beautiful Hallway Boy (Am I supposed to call him Étienne or St. Clair?) drops his bag and slides into the remaining seat between Rashmi and me. “Anna.” He’s surprised to see me, and I’m startled, too. He remembers me.

“Nice umbrella. Could’ve used that this morning.” He shakes a hand through his hair, and a drop lands on my bare arm. Words fail me. Unfortunately, my stomach speaks for itself. His eyes pop at the rumble, and I’m alarmed by how big and brown they are. As if he needed any further weapons against the female race.

Josh must be right. Every girl in school must be in love with him.

“Sounds terrible. You ought to feed that thing. Unless ...” He pretends to examine me, then comes in close with a whisper. “Unless you’re one of those girls who never eats. Can’t tolerate that, I’m afraid. Have to give you a lifetime table ban.”

I’m determined to speak rationally in his presence. “I’m not sure how to order.”

“Easy,” Josh says. “Stand in line. Tell them what you want. Accept delicious goodies. And then give them your meal card and two pints of blood.”

“I heard they raised it to three pints this year,” Rashmi says.

“Bone marrow,” Beautiful Hallway Boy says. “Or your left earlobe.”

“I meant the menu, thank you very much.” I gesture to the chalkboard above one of the chefs. An exquisite, cursive hand has written out the morning’s menu in pink and yellow and white. In French. “Not exactly my first language.”

“You don’t speak French?” Meredith asks.

“I’ve taken Spanish for three years. It’s not like I ever thought I’d be moving to Paris.”

“It’s okay,” Meredith says quickly. “A lot of people here don’t speak French.”

“But most of them do,” Josh adds.

“But most of them not very well.” Rashmi looks pointedly at him.

“You’ll learn the language of food first. The language of love.” Josh rubs his belly like a skinny Buddha. “Oeuf. Egg. Pomme. Apple. Lapin. Rabbit.”

“Not funny.” Rashmi punches him in the arm. “No wonder Isis bites you. Jerk.”

I glance at the chalkboard again. It’s still in French. “And, um, until then?”

“Right.” Beautiful Hallway Boy pushes back his chair. “Come along, then. I haven’t eaten either.” I can’t help but notice several girls gaping at him as we wind our way through the crowd. A blonde with a beaky nose and a teeny tank top coos as soon as we get in line. “Hey, St. Clair. How was your summer?”

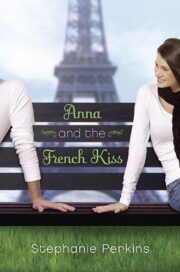

"Anna and the French Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Anna and the French Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Anna and the French Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.