"Yes, but not before you feed me — there was nothing edible on the boat." He took my hand, and we walked slowly back to the villa, where Cécile rejoiced at his appearance. She insisted that we celebrate his arrival and immediately began discussing plans for a feast with Mrs. Katevatis, who, in typical fashion, had soon invited the entire village to dine with us. The food was, as always, incomparable, and the amount of ouzo consumed led to some particularly raucous dancing. Colin took to Greek folk dancing well, cutting a fine figure with Cécile and the villagers. The festivities did not break up until late in the evening, and although I was exhausted by the time I fell into my bed, I found that I could not sleep. I paced restlessly on my balcony for some time, calmed by neither the stars nor the sound of the ocean. Suddenly my eyes caught something below me; I had left a book on the white wall at the edge of the cliff and decided to get it before the wind blew it into the water.

I went downstairs, stepping quickly, the stone floor of the veranda cold on my feet. The book, my poor abandoned Timaeus, collected, I paused for a moment to look at the caldera, when I saw Colin sitting in a chair only a few feet away from me.

"Why aren't you asleep?" I asked as he stood and walked toward me.

"Morpheus seems to have eluded me completely tonight," he said. The skirts of my nightgown and my long hair billowed around me in the wind as I took his hand. "You are cold."

"A little," I admitted. "I couldn't sleep either. Your arrival has forced me to realize how much I have missed you, when all this time I thought I had found perfect contentment. I shall never forgive you for disillusioning me."

"What can I do to redeem myself?" he asked, putting his arms around me.

"I cannot say. You might start by kissing me again."

He obliged me immediately and thoroughly. "I hope that was satisfactory."

"Perfectly," I murmured, resting my cheek against his.

"The difficulty, of course," he continued, "is that it does not address the long-term problem."

"Is there a long-term problem?"

"Of course. Now that I know you shall miss me, how can I possibly leave you again?"

"There's no need to think about leaving; you've only just arrived."

"But eventually I shall have to go, and I have found being without you a severe impediment to my happiness. I am afraid there is only one solution to our predicament."

"What is that?" I asked, kissing him. He was unable to respond for several minutes.

"I want you to give me your heart, Emily. I want you to marry me," he said. "But I know your views on that subject. I would not want you as my wife unless you truly believed that marrying me would complement a life you already find perfectly satisfying."

Although the idea of spending my life with Colin struck me as very attractive on a number of levels, I was not willing to commit to something that would so radically affect my personal freedom. Perhaps later, when I had a more precise idea of how I wanted to live my life, I would be in a better position to judge how he could fit into it. For now, though, I was not prepared to abandon my autonomy and did not want to feel obligated to anyone. An odd thought crossed my mind.

"Whom do you prefer: Hector or Achilles?" I asked.

"What kind of a question is that?"

"Hector or Achilles?"

"Hector, of course," he said, looking confused. "'Sprung from no god, and of no goddess born; / Yet such his acts, as Greeks unborn shall tell, / And curse the battle where their fathers fell.'"

"And you did express an interest in taking me to Ephesus, if I remember correctly. I believe it was on the Pont-Neuf?"

"So long as you are willing to uphold your pledge to leave your evening clothes behind."

"Cécile is right," I said, laughing. "She has always told me that you are a man of great possibility."

"Perhaps I should propose to her," he replied, raising his eyebrows.

"She undoubtedly would accept you." I rested my hand on his cheek. "I, however, have no intention of marrying again." He did not take his eyes from mine, even as they exposed the pain my statement caused him. I paused. "But, faced with such a suitor, I am willing to allow for the possibility."

"What does that mean?"

"I am giving you permission to court me, Mr. Hargreaves," I replied, placing my fingers lightly on his lips. "But I can offer you no promises." He pulled me close and kissed me passionately, apparently satisfied with my response.

"Perhaps just one promise?" he asked, brushing my hair from my eyes.

"What?"

"Promise that you will not be too hard on me. I've no goddesses lining up to help me convince you."

"No promises, Colin," I said, and kissed him very sweetly before returning to my bed.

The history behind the story

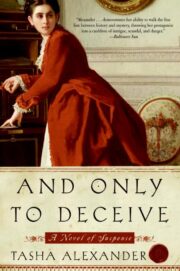

On writing And Only to Deceive

One day, while I Was engrossed in Dorothy L. Sayers's wonderful Gaudy Night, a sentence leapt off the page at me:

If you are once sure what you do want, you find that everything else goes down before it like grass under a roller-(all other interests, your own and other people's.

I had been saying for as long as I could remember that I wanted to be a writer. Now I realized that if that was truly what I wanted, I had to sit down and write a book. No more excuses. At the time, my son was three-and-a-half years old and had reached the age where he stopped napping. I had to take advantage of every free moment I had-and in bursts of fifteen minutes, a half an hour, whatever time I could steal-I spent the next two months writing the first draft of And Only to Deceive.

I knew I wanted to write about an English woman in the late Victorian period and had a strong image of her standing on the top of the cliff path on the Greek island of Santorini, one of my very favorite places. Once I started asking questions about how she came to be there, the story started to invent itself.

I was determined not to create twenty-first-century characters, drop them into bustles and corsets, and call them historical. Fundamentally, we may have much in common with those who lived before us, but sensibilities have changed greatly. A strong-minded young woman in 1890 would not think in precisely the same way one would today. Emily's search for independence had to make sense in the context of the society in which she was raised. So she rebels in small ways at first, gradually becoming more steadfast in her convictions, more confident in herself, but she's vulnerable because she's not prepared to absolutely renounce her position in society. And, really, I think it's that sort of compromise for which we all search: How much of our culture, our society, do we accept? How much do we reject? Can we live according to our principles without sacrificing anything? It's very easy to have strong opinions when holding them does not threaten the comfort of our daily life.

The paramount goal for an aristocratic woman in Victorian England was to make the best possible marriage, one that would preserve fortunes and estates while increasing her standing in society. The marriage market was a competitive one. A family might have many eligible daughters but could only have one eldest son, who, alone among his brothers, stood to gain a significant inheritance. A young lady would feel a great deal of pressure to catch a respectable husband in as few seasons as possible after making her social debut. If two or three years passed and she was not engaged, she would be considered a failure.

Emily, coming from a wealthy, titled family, would have been in an excellent position to make a good match, and although I wanted her to be independent, it would have made no sense, historically speaking, for a girl in her position to avoid marriage. Her parents would never have allowed it. As an unmarried woman, she would be subject to her mother's rule, a situation, that, given Lady Bromley's character, would hardly have allowed her to do the things I wanted. But I did not want her to be married. A Victorian gentleman, even an enlightened one, would still have a decidedly Victorian view of marriage. To make her a widow seemed the perfect solution. I would be able to give her a certain degree of freedom without having to sacrifice historical accuracy.

Once I had Emily's character and situation firmly in my mind, I started to consider what might inspire in her an intellectual awakening. I've always been struck by the graceful beauty of classical art and fascinated by the enduring nature not just of Homer's epic poems, but of Greek mythology in general. It's astounding to me that these stories, first told more than two thousand years ago, still resonate with people. Can you imagine writing something that could permeate Western culture for that long? I'd be afraid even to try!

Regardless of how many times I've read The Iliad, I always hope, hope, hope that this time Achilles won't kill Hector, even though I know it's impossible. I fling the book across the room every time I get to the part where Hector dies. I can't help it. It slays me. But that's part of the brilliance of the story; even though we know what happens, we still care desperately about these characters.

(If you like Hector, read the lovely, heartbreaking poem Irish poet Valentin Iremonger wrote about the night before the Trojan hero's death.)

As I was concocting the plot for the novel, I decided to have part of the intrigue involve art forgeries, which can be immensely difficult to detect. Two of the pieces I've mentioned in the book, both pointed out as fakes by Mr. Attewater, were actual objects found in the museum. The first, a bust of Julius Caesar purchased by the British Museum in 1818 for approximately thirty pounds, was not only exhibited, it was reproduced extensively as well, becoming one of the most famous images of the great Roman. It is not an ancient piece at all, dating instead from approximately 1800.

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.