"I find it interesting that when faced with evidence, you attempt to discredit the source rather than proclaim your own innocence. Whatever Philip's faults, he was not a criminal." I hoped this was true. If it was not, I fully expected that Andrew would quickly blame everything on his accomplice. "I must admit it surprises me to learn that you managed to orchestrate such an extraordinary series of thefts; I would not have thought you capable of pulling it off."

He bristled visibly at this comment. "I will not respond to such preposterous accusations," Andrew snapped, his cold eyes fixed on me.

"And I, Mr. Palmer, have heard quite enough," Lord Lytton said, motioning to Monsieur Fournier, who pulled a bell cord.

The two gendarmes I had arranged to have waiting in the house entered the room and bound Andrew's hands. "You are under arrest for having stolen Monsieur Fournier's ring. Do not doubt that further charges will be filed. Madame du Lac's testimony was quite compelling."

16 SEPTEMBER 1888

HÔTEL CONTINENTAL, PARIS

Left K most reluctantly yesterday morning, after a decidedly sleepless night. Had I not such expectations, both for the hunt and for the conclusion of this game in which I have become involved, I think I would not have quit England. Hope she will be grateful for a less distracted husband upon my return.

Have arranged for Renoir to paint a portrait of my darling wife; I do not think another artist could so accurately capture the brightness residing in her.

34

The hours that passed after Andrew was taken away slipped by me unnoticed. Madame Fournier put me into one of her sitting rooms, sent for Cécile, and plied me with tea and more than a little cognac. Needless to say, her husband was delighted to have his ring returned, but he was even more pleased at having had a hand in the downfall of Caravaggio. Lord Lytton congratulated me heartily and told me that he would send someone to speak to me about the case as soon as possible. Sometime later Colin Hargreaves walked into the room. Cécile, considerably more composed than I, spoke at once.

"I must say, Monsieur Hargreaves, that your arrival is completely unexpected. Am I to assume that this means you are not in league with Caravaggio? I hoped that such a face would not be wasted on a criminal."

"I'm afraid I have a significant amount of explaining to do," he replied.

"I have no plans for the evening, monsieur," she said, motioning for him to sit. "Perhaps if you begin now, you could finish before dinner."

He ran his hand through his hair and looked at me. "I have been looking into the matter of Caravaggio for some months."

"How interesting," Cécile exclaimed. "Are you a spy, Monsieur Hargreaves?"

"Not at all," Colin said, laughing. "I am occasionally called on by Buckingham Palace to investigate matters that require more than a modicum of discretion. Rumors of forgery and theft at the British Museum have circulated for some time, and it had become clear that some involved were members of the aristocracy. Her Majesty, as you might imagine, prefers such things to be dealt with as quietly as possible."

"So you have been following Andrew all this time?" I asked.

"Partly, but I have also been following you, Emily, in a vain attempt to keep you out of danger. Shortly before the Palmers joined us on that last safari, Ashton confided in me that he had discovered their involvement in some sort of underground activity. He would tell me no details, insisting that he had the situation well in hand, and that he planned to confront them when they arrived in Africa."

"Perhaps he wanted to give them a chance to end things honorably?" I suggested.

"Yes, he unfortunately assumed that they would hold to a code of gentlemanly behavior similar to his own. He rather liked the idea of handling everything alone, imagining himself as some sort of classical hero."

"But when did you learn of the thefts?" Cécile asked.

"Shortly after I returned to England following Ashton's death. I did not connect him or the Palmers to any of it until Andrew started to show such an interest in you, Emily."

"Is it so astounding that a man would fall in love with Kallista, Monsieur Hargreaves?" Cécile said, arching her eyebrows.

"Not at all, I assure you," he replied. "It was, however, astounding that a man of Andrew's decided lack of intellect would show any interest in investigating Ashton's papers."

"He did that for his father. Lord Palmer asked me for them himself," I protested. "I have seen the manuscript."

"If you knew Andrew better, you would know that he never, on any other occasion, has done anything on behalf of his father. His adult life has been spent deliberately vexing the poor man, squandering his fortune, and generally causing him as much grief as possible. He had no respect for his father's passion for antiquities. In fact, all this began when Andrew sold pieces of Lord Palmer's collection to cover gambling debts. He replaced the originals with good copies. His father never suspected a thing.

"Pleased to have a new source of income, Andrew began spending more and more. Once his father's collection had been copied and sold, he and Arthur, confident in their success, decided to expand their operation. His father's reputation enabled the son to get whatever special access to the museum he requested, even after hours. The forger would then make sketches, molds, whatever he needed to copy the piece Andrew had decided to steal. Once the forgery was complete, Andrew could switch it for the original when the museum was closed. If he ran into trouble, he found an obliging night guard who was easily bribed to let him in. The artifact would be sold on the black market. It seems there are endless unscrupulous buyers willing to purchase such things."

"I am afraid that I thought Philip was guilty," I admitted, telling him what I had found in the library at Ashton Hall and of the information Cécile had gathered about my husband's black-market activities.

Colin sighed and shook his head. "I admit that I, too, suspected him initially, when I first learned he was well known on the black market. That is why I questioned you about purchases he made on your wedding trip. The day when you confessed to me your...er, feelings toward Philip, I thought you were going to tell me that you knew something about his illegal purchases."

"Why did Philip collect all the stolen pieces?"

"He wanted to have all the originals in his possession before he confronted the Palmers. When they joined us in Africa, he told Andrew all he knew and asked him to put an end to the scheme and return what had been taken from the museum."

"How did you learn all this?"

"As I said, I've been investigating the matter for some time. I suspected that both the Palmer brothers were involved, but unfortunately they left very little tangible evidence. When Lord Lytton told me that Andrew had been arrested, I confronted Arthur. He told me that Ashton had asked for nothing more than Andrew's word as a gentleman that they would stop."

"Andrew gave his word?"

"There are few other things he would give away so easily."

"But surely he knew that Philip would expose them if they did not stop. Perhaps he did mean to abandon the enterprise."

"Andrew is not the type of man to give up what he views as an easy source of income."

"And once Philip fell ill, there was no incentive for Andrew to stop." I paused and looked at Cécile. She held my gaze and nodded almost imperceptibly. "What a convenient coincidence that Philip did not return from Africa." Colin began to step toward me, then stopped. Cécile took my hand as the reality of what had happened slowly seeped into my consciousness. "Andrew killed him, didn't he?"

"I'm so sorry, Emily. I do not think we would ever have learned of the murder had Andrew not been arrested before Arthur. The Crown is indebted to you. Arthur, it seems, is much concerned with his own fate and wanted to make it perfectly clear that he was only an accomplice. He told me that on the way to our safari camp he acquired from an obliging tribesman a poison used on blow darts. Andrew must have slipped it into Ashton's cup when he was pouring champagne for all of us. I had never suspected that he died of anything but natural causes. As I have told you, Ashton had been tired for most of the trip, but I suppose that was due to his worry over confronting his friends."

For some time I could not speak, able to think only of my poor, murdered husband. I knew that Philip had left no records that implicated Andrew; I had lied about finding them in an attempt to goad him. Philip, true to his own code of ethics, had wanted nothing more than for his friends to stop their thievery. He never had any intention of bringing them to justice. A sob escaped from my throat, and Cécile took me in her arms while Colin politely pretended to look out the window. My tears were short-lived, however; I had already mourned the death of my husband.

Cécile wiped my face with her handkerchief, smoothed my hair, and marched over to Colin. "And why did this contemptible murderer try to forge a relationship with Kallista? He would have been better to avoid her entirely," she said.

"Andrew believed that Ashton had records that would prove his guilt. Ashton had said as much in Africa. The Palmers tried on numerous occasions to find them, but to no avail. Andrew bribed a servant-a footman, I believe-to search Philip's papers in the library but met with no success. Arthur broke into Emily's suite at the Meurice."

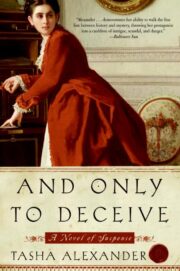

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.