"Are you ready for our trip, Meg?" I asked.

"Oh, Lady Ashton, I think you would be much better off taking Mr. Davis or someone else," she said reluctantly.

"Nonsense, Meg. You shall enjoy yourself immensely, and I need you. Davis's place is here." She and my butler were the only members of the household who knew the true nature of my excursion; the rest thought I was going to Ivy's country house. Meg, for all her hesitation at consorting with foreigners, was a model of efficiency under any circumstance. Furthermore, no one else could match her skills in arranging hair. Davis would have been a singularly useful addition to nearly any expedition, but to take him would be unthinkable. Why on earth would my butler travel with me to someone else's house?

"Yes, madam," Meg replied halfheartedly.

I adjusted my hat and, with a final glance in the mirror, swept out of the room, past the commanding portrait of Philip's father in the hallway and down the wide staircase.

"Goodness, Emily, you look as if you could fly!" Ivy exclaimed.

"I am ecstatic at the prospect of some time in the country," I said, winking at Davis, who struggled to maintain his dignified posture.

"I sent your trunks to the station before breakfast, Lady Ashton, with precise written instructions for the porters."

"Thank you, Davis. I shall wire with any news," I whispered to him, patting his arm.

"Take care, madam," he replied. "We hope to have you home again very soon."

Within an hour Meg and I had settled snugly into our train. Margaret went to the station to see us off, and I waved frantically to her until the train pulled far from the station. The cold landscape outside the window made me feel doubly warm and exceedingly comfortable in our cozy private compartment. Andrew and Arthur sat with us for the beginning of the journey and then retired to their own compartment on the other side of the corridor.

"It is an excellent day to travel," I said to Meg when we were alone.

"But the weather is dreadful, Lady Ashton."

"I have always liked traveling by train in inclement weather. One is completely isolated from the elements and whisked away to emerge at a destination where the weather may be entirely different."

"I'm afraid it will be a rough time crossing the Channel, madam."

"I shouldn't worry too much, Meg." I remembered how seasick she had been during our return from Paris and wanted to put her mind at ease. "We shall hope for calm waters. Have you started your book?"

"Not yet, madam. There was no time, what with all the packing to tend to."

"You are free of all such distractions at present. Try to enjoy the journey, Meg." As she picked up her Amelia Edwards, I rummaged through my bag in search of a book for myself. I had taken Philip's copy of King Solomon's Mines from the bedroom at Ashton Hall and soon was engrossed in Mr. Haggard's story of adventure in Africa. Presently Meg asked if I was hungry and produced a spectacular picnic lunch, which I invited Andrew and Arthur to share with us. They appeared as unsettled at the prospect of dining with my maid as she was at eating in the company of gentlemen, but I did not pay them any notice.

Soon we reached Dover, whence a steamer would take us to Calais. Meg's face was still tinged green when, hours later, we boarded a train to Paris. My thoughts of calm seas of course had no effect on the Channel, which was at its choppiest, taking away any hope poor Meg might have had for a pleasant crossing. Andrew and Arthur fared no better than my maid; I alone did not fall sick on the ship. My companions staggered onto the train and were all asleep within moments of our departure from the station, leaving me to my reading. Rather than return to King Solomon's Mines, I turned instead to my Greek grammar. I had spent sadly little time on my academic pursuits while preparing for my journey and did not want to fall hopelessly behind. After passing nearly half an hour staring blankly at a passage I could not focus on enough to translate, I opened Philip's journal. I had already read the parts that pertained to myself but now wanted to peruse it in its entirety. The volume I carried with me spanned a period from the year before our engagement through the time of Philip's disappearance. I hoped that reading it would provide me with a greater insight into the character of my husband.

The early entries in the volume had been written in Africa and chronicled what evidently was a thoroughly satisfactory hunt. For over a month, Philip, Colin, and their fellows stalked more types of prey than I care to remember. Colin appeared to have spent more time trekking through the countryside than hunting, for which I admired him. Philip was in his element, tracking prey and planning strategies; he filled page after page describing the process in maddening detail. Clearly he loved what he was doing. I, however, found the topic rather boring and had a difficult time doing more than skimming the pages. I was thankful when the party eventually returned to Egypt, where they played tourist for another month. Philip's descriptions of the monuments of Egypt were not particularly inspiring, but for this I could forgive him. Greece, not the land of the pharaohs, was the area of his expertise.

I closed the book and gazed out the window as the train ripped through the French countryside. It had been very easy to fall in love with Philip when I believed him to be dead. Looking at his journal brought to mind the reasons I had never been interested in him in the first place; hunting encompassed a terribly large part of him, and it did not interest me in the least. How would I feel next year if he wanted to leave me home for three months while he cavorted around Africa?

I shook off these troubling thoughts and continued to read. Philip had spent the spring in London; this was the time during which we met. Rereading these passages dissipated my melancholy, and once again my heart filled with ardor for the man who had written so beautifully as he fell in love with me. I found mention of the Judgment of Paris vase and an account of his decision to purchase both it and another vase. To this point there had been not a word of anything that I could interpret as underhanded or suspicious in the least. The only surprising revelation was the fact that he'd brought to the villa an English cook. Despite his love of the Greek countryside, he did not fully embrace the culture.

To this day it distresses me to admit it, but reading Philip's journal in detail proved rather tiring; I began skimming again. Our engagement, a trip to Santorini, another African safari, our wedding, our wedding trip, flew past me in short order. After considerable deliberation he donated the Paris vase to the British Museum shortly before our wedding and did not write about it again. It was just as Mr. Murray had told me. I skipped ahead to Philip's last entries, which unfortunately gave me none of the information I had hoped to find. He spoke of Colin in the warmest of terms, even in his account of their final argument.

"Achilles heard, with grief and rage oppress'd; / His heart swell'd high, and labour'd in his breast. / Distracting thoughts by turns his bosom ruled..." Hargreaves cannot understand what I am doing, and we argued bitterly, but of course he supported me in the end, as he always does. Nonetheless, I shall not let him be my Patroclus.

I wasn't entirely sure what that last phrase meant. Did it suggest that, although they were friends, he would not consider Colin to be as close to him as Patroclus was to Achilles? Or was Philip attempting to protect Colin, by not accepting an offer of assistance? Achilles allowed Patroclus to fight for him, and his friend died in battle. Although I could not make complete sense out of Philip's statement, I could not but think that it must pertain somehow to the forgeries.

Philip was buying stolen antiquities; that much was certain. Perhaps Colin was the one who had them copied and removed the originals from the museum. Philip, after our marriage, may have decided to stop his nefarious activities and told Colin that he would no longer be a buyer. He may have gone a step further and told Colin to stop the thefts altogether, giving him the opportunity to reform himself. Colin, unwilling to abandon a profitable enterprise, would have argued with Philip, not comprehending why his friend had suddenly changed his feelings about their activities. This made sense to me. Marriage would make a gentleman more aware of the importance of his code of ethics and morals. The two friends may have started down their illegal path together by letting a joke or a challenge go too far. Philip recognized that the time had come to stop; Colin was not ready. His friend, although they had been close for years, would never be his Patroclus.

None of this was of much concern to me at the present; before long I would be reunited with Philip and insist that he reveal everything, but I liked trying to decipher the puzzle. I wondered if the time had come for me to bring Andrew into my confidence. I did not require his assistance but would very much have liked to have his emotional backing in my quest to reveal Colin's thievery. As I considered my options, he opened his eyes and smiled at me. I decided instantly to leave him alone. I had caused him suffering enough.

The conductor tapped on our door and told us Paris lay only a few miles away. Soon I felt the train begin to slow, and I shook Meg gently to wake her. We had arrived. Monsieur Beaulieu greeted us on the platform and escorted us back to the Meurice, where he put me in his best suite, assuring me that he had personally overseen the changing of the locks only that morning. I convinced him that I felt perfectly safe in the hotel, thanked him for his hospitality, and then told Meg to leave until morning what little unpacking she had to do. We would spend only enough time in Paris for Andrew to tie up his business, and I planned to enjoy myself thoroughly while I waited for him.

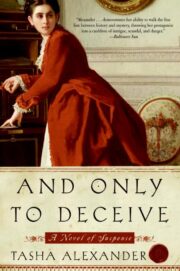

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.