"Not quite," Lord Palmer corrected. "It is the piece that inspired innumerable Wedgwood copies, but they were done in jasperware rather than glass. There was a prize offered to anyone who could duplicate it in glass. The chaps who won were so successful that we are now barraged with cameos in all forms."

"I should love to have something so beautiful for my own," Arabella said.

"You could, my dear, for the right price," Arthur said, his uneven teeth marring his smile.

"Oh, I should never want a copy. I'll follow Lord Ashton's example and stick to originals."

"All originals have a price, Arabella, even those in museums." He laughed, and I looked at him, wondering what he could possibly mean by such a statement. Before I could inquire, he took Arabella's arm and whispered something that made her laugh loudly. Mrs. Dunleigh then asked Lord Palmer if we could see the Rosetta Stone, adding that it was the only thing she considered really worthwhile in the museum. I closed my eyes and sighed, realizing that the sooner our excursion ended, the better.

The next few weeks found me in Andrew's company more than ever. He took me to the theater, to dinner, and we walked together in the park frequently. At soirées he brazenly monopolized me, something to which I rarely objected. His sarcastic commentary on the scenes before us was always more entertaining than the polite, nonsensical conversation to which I was accustomed. He possessed a seemingly incompatible way of disregarding some rules of society at the same time as he rigorously upheld others. Nonetheless, he grew more charming with closer acquaintance, and I determined that the rules he chose to uphold were the ones he thought would protect me. A foolish effort, of course, but I appreciated it regardless.

My mother did not entirely approve of my spending so much time with Andrew. She liked his family, of course, but felt that I could do better. In her mind, given my own title and fortune, I should be able to attract the most eligible men in the empire. Andrew was heir to a large estate, but one that included very little cash. The property he stood to inherit would make it easy for him to secure generous lines of credit, and I assumed that this was how he, like many gentlemen, supported his flamboyant lifestyle. This, of course, did not impress my mother. The fact that Andrew and I did not observe the social niceties troubled her greatly, and she admonished me to change my behavior lest I ruin my chances of remarriage. Contrary to her intentions, her concerns served only to encourage me.

My becoming more familiar with Andrew did little to fade the specter of Philip's memory; if anything, it intensified it. After spending an evening with Andrew, I would go home to my empty bed keenly missing my husband. How unfair that I had never laughed with Philip, that I had never teased him, that I had never flirted with him. I thought of our wedding trip and how, when I retired before him, I would lie awake anxiously wondering if he would rouse me when he came to bed, always hoping just a bit that he would. Although he did not inspire any passion in me, I did enjoy our physical encounters; if nothing else, they certainly satisfied my curiosity.

The memory of Philip did not trouble Andrew; as far as he was concerned, the dead are dead and it should be left at that. He did speak about Philip periodically and told me many stories about their friendship. As always, I devoured any new information about Philip, and everything Andrew told me confirmed my belief that my husband had been an extraordinary man.

Margaret, though supportive of anything I did in an attempt to reject society, was not overly fond of Andrew. She said he distracted me from my work, an observation that, while not wholly untrue, I considered unfair. I met with Mr. Moore, my tutor, three mornings a week, and he had been both surprised and pleased by my quick progress toward learning ancient Greek. The only point of contention between us was that I wanted to translate Homer; Mr. Moore insisted that I start with the Xenophon, which was written in the standard Attic dialect spoken in Athens. Margaret and I attended numerous lectures, at both the British Museum and University College, and we hoped to descend upon Cambridge in the near future. What, precisely, we would do there, I was not entirely certain, but I had no doubt that Margaret would come up with something marvelous. If Andrew were less than enthusiastic about our plans, he never suggested that I should abandon them.

Though she would not admit it to me, Ivy clearly harbored the hope that I might marry Andrew. My dear friend longed to see me share the happiness the married state had brought her. Nonetheless, although I thoroughly enjoyed the time I spent with him, I still had no intention of marrying; I did not want to relinquish control of my life to anyone.

We lunched together frequently at my house, spending an hour in the library afterward before he left for his club. Ivy felt this to be consummate proof that we were near marriage, despite my protests. I was happy to have someone with whom to dine on a regular basis; being a widow sometimes felt very lonely.

"I don't understand why you spend so much time in the library," Andrew said after one of our lunches. "Why don't we go to the drawing room?"

"I much prefer it here. The wood has such a feeling of warmth, and I find being surrounded by books to be greatly comforting."

"You are a funny girl," he drawled, sliding closer to me on the settee.

"I like thinking of Philip in here. Colin tells me that they spent many happy evenings in this room."

"Spare me Hargreaves's opinion, if you don't mind." He stood up and paced in front of my husband's desk.

"Why do you dislike him so?"

"I don't dislike him; I just have never felt I could trust him."

"Has he done you some grave injustice?" I asked mockingly.

"Not precisely, but he's the sort of man who is very difficult to read. Do you know him well?"

"No, I suppose not, but he's always seemed to be very straightforward. Philip thought his integrity beyond reproach."

"Well, I've always valued Ashton's opinion, but I fear in this case he may have been deceived. Hargreaves spends too much time rushing around on spur-of-the-moment trips to the Continent. If you ask me, he's either up to no good or has a very demanding mistress in Vienna."

"You are too terrible!" I cried. "I rather like Colin."

"And that, my dear, is his biggest flaw." He sat close to me again. "I feel so alive when I am with you."

"I know. I can see it in your face."

"Yet you give me no indication of your own feelings," he said, frowning slightly.

"I am a very respectable widow still in mourning. Please do not try to ruin my character," I reprimanded him, laughing.

"You shall be the death of me," he said, taking my hand.

"Shall I summon help? Or perhaps I should leave you to die so that Arthur inherits. It would be better for Arabella should your brother ever propose," I said, smiling at him.

"I die a thousand deaths in your presence every day," he said, moving even closer to me as he brought my hand to his cheek. "Forgive my impertinence."

"For what?" I asked.

"This," he replied, leaning forward and kissing me fiercely on the lips. I tried to pull back but quickly lost interest in doing so and instead let his mouth explore mine. Eventually I pushed him away.

"You are a beast, and I should insist that you leave immediately."

"But you won't, will you?"

"No. But I will ask my mother to chaperone every time I see you in the future," I said flippantly. I did feel rather uncomfortable and hoped he would leave soon. He stayed another half hour before going to his club. As soon as he was gone, I started to cry, wishing desperately it had been Philip's kisses that I so enjoyed.

1 JULY 1887

BERKELEY SQUARE, LONDON

"Persuasive speech, and more persuasive sighs, / Silence that spoke, and eloquence of eyes."

I am determined to propose to K before the end of the week and must decide what I shall say, to both her and her father. Hargreaves assures me that any reasonable woman would accept me for my wine cellar alone. While I do not doubt that she will agree to marry me, I would like to have an eloquent speech for the occasion. Regardless of my confidence, I cannot help but feel a great deal of anxiety when contemplating such a significant step.

15

Several days later the restorer recommended to me by Lord Palmer delivered my bust of Apollo, beautifully repaired, along with a note. Apparently, because the artisan who completed the work determined that the piece was beyond a doubt a fourth-century-B.C. original, he felt the need to suggest that I take better care of it.

My heart raced as I reread the note. My mind kept going back to the comment Arthur Palmer had made to Arabella in the Roman gallery that any original, including those in museums, could be obtained for a price. Everyone agreed that Philip's integrity was of the highest. Why, then, did he have in his possession a piece that clearly belonged in the museum? I flung myself onto the settee.

Davis, whose entrance I had not noticed, cleared his throat. "Mrs. Brandon, madam." Ivy, stunning as always in a fashionable walking dress, followed him almost immediately, and I embraced her when she came into the room.

"I don't know when I've been so happy to see anyone, Ivy."

"Goodness! I shall have to call more often," my friend exclaimed. "You look a trifle pale, Emily. Are you unwell?"

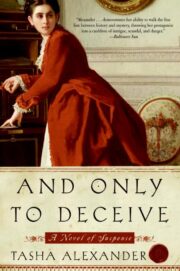

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.