Andrew immediately interrupted me. "If you force me to think about prep school, I shall have no choice but to resort to kissing to silence you."

"Then I shall say nothing more. Come with me, and I will try to find what your father needs." We walked to the library, where I sat down at Philip's desk, opened one of the drawers, and pulled out a pile of papers. The manuscript was nowhere to be found. "I'm very sorry, Andrew. Please tell your father that I shall keep looking. It's sure to be filed away somewhere."

"I'd happily do it for you if it weren't such a beautiful day. I want to go riding. Come with me?"

I did not reply.

"Emily? Are you all right?"

I nodded. "Fine, Andrew. Just a bit distracted. What did you say?"

"Want to go riding with me?"

"Not at the moment, thank you." My eyes rested on a small piece of paper, not unlike the one I had found earlier in Philip's guide to the British Museum, that was pushed into the back of the desk drawer. I waited until Andrew left to remove and open it. The handwriting was identical to that on the first note. Its message was brief: "Grave danger."

26 JUNE 1887

BERKELEY SQUARE, LONDON

Fournier has had his revenge; purchased a spectacular Roman copy of a Praxiteles discus thrower before I even knew it was on the market. Am devastated. He kindly invited me to view it next time I am in Paris, an opportunity that will come sooner than expected, as I plan to stop there on my way to Santorini in August.

Saw Kallista at Ascot last week; she had little to say to me but at the same time gave no suggestion that my attentions are unwelcome. Her beguiling innocence must explain her actions.

14

I compared the handwriting on the note with every document I could find in Philip's desk, carefully analyzing each invoice, receipt, and letter. Nothing matched. Furthermore, my husband's papers could not have been more mundane and gave no indication of what he might have been doing to receive such unsettling correspondence. I locked the note in a desk drawer, next to the other note and the gentleman's glove.

After a quick luncheon, I changed into an afternoon dress and prepared to leave the house.

"Davis? Where is my bust of Apollo?" I asked, adjusting my hat, which, although black, was still rather smart, in the hall mirror before heading to the front door.

"I'm very sorry, madam. The new parlormaid knocked over its pedestal while she was dusting this morning and broke the nose off the statue. I did save the pieces in case you wish to have it fixed," Davis replied as he opened the door for me.

"Thank you, Davis. Don't be too harsh with her; I'm sure it can be repaired adequately," I said, walking out of the house. I had crossed the tree-filled park in the center of Berkeley Square and was heading to Bruton Street when Colin Hargreaves approached me.

"Mr. Hargreaves, where have you been hiding?" I asked.

"I've been meaning to call on you for some time, but business did not allow me the pleasure until this afternoon."

"Well, as you see, I am not at home. In fact, I am on my way to the British Museum."

"Surely you do not plan to walk the entire distance? Your carriage would be much quicker."

"It's a fine day for a walk. I always feel I must take advantage of a sunny day."

"There is something most particular about which I would like to speak with you. May I join you?"

"I don't see why not." I took the arm he offered, and we continued up Conduit Street. As always, his touch made my skin tingle and brought a smile to my face.

"Do you have any record of the antiquities Ashton purchased in the final months of his life?"

"I imagine so; he kept meticulous records. Why?" I thought back to the receipts I had seen that morning. None had been for antiquities.

"No reason in particular. Did he show you the things he bought?"

"No. I had no idea that he owned such things. You know they were not on display in the town house."

"Of course. He had a splendid gallery in Ashton Hall. You haven't seen it?"

"I've never been to the estate."

"That's rather odd, don't you think?"

"I never really thought about it." I looked at him, wondering where this line of questioning would lead. "We returned to London after our wedding trip, and Philip left almost immediately for Africa."

"Did he ever suggest that you go while he was in Africa?"

"No, quite the contrary. He told me that the house was something of a shambles and suggested that I stay in London."

"Surely you could have directed the servants to prepare the house."

"I cannot imagine why you are so concerned about this, Colin." We began walking again. "I passed the fall with Ivy on her parents' estate. Why would I have wanted to sequester myself in Derbyshire, away from all my friends?"

"Do you remember Ashton shopping for antiquities while you were on your wedding trip?"

"No, I don't."

"Did he ever leave you to conduct business during your travels?"

"Yes, he did. Is that so uncommon?"

"No, but it would be of great assistance to me if you could remember what he was doing."

"I never asked him. Why all these questions? Had Philip discovered some new archaeological secret? Some long-forgotten Greek vase?"

"No, I'm not suggesting any such thing. I'm wondering if he left any unfinished business that should be completed."

"It's awfully late to be considering that, isn't it? Lord Palmer has asked me to look for papers on one of Philip's projects. He plans to edit and publish the material. I imagine that any of Philip's nonacademic business has long since been taken care of by his solicitor."

"What sort of papers are they?"

"They're the draft of a monograph. Why are you so interested?"

"I've already said more than I ought." He paused at Tottenham Court Road. "Shall we turn here or continue in Oxford Street?"

"I thought I would go up Bloomsbury Street," I replied. We walked in silence until we reached Great Russell Street, where Colin deposited me at the entrance to the museum.

"Please excuse my questions if they seemed strange. I only want to help." I watched him rush back to the street and hail a cab. I shook my head, curious to know what on earth had prompted him to become so belatedly concerned with my husband's business affairs. Could Colin have written the notes?

Looking at my watch, I realized that I was late for my rendezvous with Lord Palmer, who had promised to give me his own tour of the Greco-Roman collection. Once inside, I found him quickly; I was a bit let down to see that Arthur Palmer, Arabella Dunleigh, and her mother accompanied him, certain that Arthur would have little to contribute to any discussion of classical artifacts.

"Andrew will be disappointed to have missed this party," Arabella said, smiling at me. She wore what had to be her finest afternoon dress, blue and green stripes of gauze and moiré over yellow taffeta, with fine lace cuffs. I don't know that I had ever seen her look so well turned out.

"My brother prefers to spend the afternoon at his club, my dear," Arthur said with a tone of familiarity that surprised me. I would not have guessed that his relationship with Arabella would progress so quickly.

"Then he must not have realized that Lady Ashton planned to join us," Arabella replied. Clearly Arthur's attentions had put her in a generous mood.

"I didn't tell him because I knew that she hoped for a serious discussion today," Lord Palmer said. "Andrew's presence would have detracted from that, I'm afraid."

"Your son's talents lie elsewhere, Lord Palmer," Mrs. Dunleigh said, smiling broadly.

"Yes, I suppose they do," Lord Palmer answered. "Come now, let's begin our tour." I wanted Lord Palmer to show me some simple inscriptions suitable for me to attempt to translate as I studied with my tutor, since I liked very much the idea of working on a text whose original form I could see in the museum. Alas, the rest of our party forced us to move through the exhibits with more speed than I would have wished.

"I'm afraid that I shouldn't have brought the others," Lord Palmer said to me quietly. "I had hoped that the young people would amuse each other and that Mrs. Dunleigh would be too busy playing chaperone to detract from our plans."

"That's all right, Lord Palmer. It's been a wonderful afternoon." I stopped in front of a blue-and-white cameo-glass vase. "This is lovely. Is it Roman?"

"Yes, early first century A.D., I believe. It is one of the more famous pieces in the museum. It must have been nearly fifty years ago now that some...ah, intoxicated bloke leaned on the case and smashed the vase. As you see, the museum staff have done a capital job of repairing the thing, although, if I remember correctly, they weren't able to make all the pieces fit."

"That reminds me, Lord Palmer, that my lovely bust of Apollo has lost its nose after a too-zealous dusting by a maid. I wonder if Mr. Murray could suggest a restorer for me?"

"I know several qualified chaps who could help you out. I'll send their names to you. I hope your butler reprimanded the maid."

"Well, it is only a copy, but I'm sure that Davis was as severe as necessary with her."

I turned around at the sound of a shriek from Arabella, who had just spotted the vase.

"I like this!" she cried.

"It is nothing more than a standard Wedgwood, my dear," Mrs. Dunleigh said.

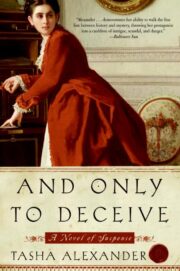

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.