"You look truly unwell. Shall I ask Davis to fetch you some tea?"

"No, please. I want nothing."

"This is about more than the break-in, isn't it, Emily? Palmer said you were utterly composed through all of it, yet-forgive me-you look dreadful now."

I gazed at his handsome face and sympathetic eyes and started to cry again.

He knelt in front of me and took my hands in his. "What is it?"

"I...I miss Philip, Colin. I really miss him."

"Of course you do, especially after going through such a ghastly experience. Had he been with you, you wouldn't have had to deal with the police yourself or worry about how you would get home."

"No, that's not what I mean." I stood up and walked away from him. "I don't know why I'm telling you any of this."

"I hope you consider me a friend, Emily, in spite of the things I said to you in the Louvre. Please believe me when I say that I never meant to offend you."

"It all seems rather irrelevant now at any rate," I said with a sigh. "You should be the last person I would trust with this information."

"You can depend on me, Emily. I would never deceive you."

"But you were my husband's best friend."

"Whatever he did, Emily, I can help you."

"Whatever he did? I would say that he never did anything; I was the one entirely at fault."

"You? How are you involved? Did it begin on your wedding trip?"

"No, it started as soon as I met him." His dark eyes fixed on my own, and I felt rather confused. "I don't think we are discussing the same subject. To what are you referring?"

"No-please, go ahead. I must be confused. What is troubling you?"

"I never loved Philip. I never even tried to get to know him; I only married him to get away from my mother." I paused and looked at Colin, who stood immobile, his mouth slightly open, as if he were unable to speak. "I see that you are shocked."

"Yes, I am," he said quietly.

"But now, now that he is dead, I have spent more than a year hearing from every person I meet how wonderful he was. I have read his journal, learned of his interests, his passions, and I find myself quite desperately in love with him." Having said it out loud, the statement seemed ridiculous even to me.

Colin moved closer to me, his eyes locked on mine. "I don't know what to say."

"Please don't think me coldhearted. I don't believe I knew myself well enough when he courted me to love anyone. I would give anything to go back and begin again."

"Thank God he never knew. He loved you completely and thought you kept a distance from him because you were innocent."

"I can tell from your tone that you are angry with me."

"Not angry. Maybe disappointed."

"Then you are unfair. My mother raised me, with the express purpose of marrying me off to the richest, highest-ranking peer possible. I never had any say in the matter. I could not study what I wished, could not pursue any interests other than those she thought I should have, and learned years and years ago that romantic feelings would have nothing to do with my marriage. Can you blame me for distancing myself from my suitors?"

"Perhaps not, but one might hope that the woman who has accepted one's proposal would at least try to make the marriage a happy one."

"I never said we were not happy. Quite the contrary. I should never have told you any of this." I stormed across the room.

"I have always thought the upbringing of young ladies to be significantly lacking. Now I have my proof."

"Can you not at least give me credit for recognizing the man he was, even if I have done so belatedly? It is not as if I married him and loved someone else. And believe me, realizing that I love him now, after his death, is punishment enough for anything I have done." Colin stared at the floor and said nothing. "I know I made him happy, Colin." I picked up the journal and shoved it toward him. "Read this if you don't believe me. He was utterly satisfied; pity me for missing my chance to share in his bliss."

"I know better than anyone how happy you made him. He told me daily." His eyes met mine again. "I suppose I am disappointed that you have shattered the myth of the perfect marriage for me."

"Really, Colin," I said.

"I am truly sorry for you that you could fail to see such love when it was in front of you." I found the intensity with which he looked at me irritating.

"Thank you. You're an excellent confidant, Colin," I snapped. "I feel much better now."

"You were right. You never should have told me any of this. I am at a loss for what to say."

"Perhaps you could change the subject. When you came in, you thought I wanted to talk about something else. What was it?"

"Nothing, really. I thought it concerned business Ashton conducted on your wedding trip. Clearly I was mistaken."

"Clearly." Evidently I would have to change the subject. "I do have a matter of business of my own with which I could use your assistance. I would like to set up some sort of memorial to Philip, maybe something at the British Museum, I'm not really certain."

"I believe it would be best if you took it up with your solicitor, Emily." I opened my mouth to speak, but he raised his hand and continued before I could form a single word. "Do not imagine I am angry with you. I think, though, that I should like the remainder of my involvement with you to be completely severed from your involvement with Ashton."

"What precisely should I take that to mean?"

"I have a difficult time reconciling the woman before me with the naïve girl my best friend married, and I fancy I should like to keep the two images separate."

"You have completely confused me."

"Then perhaps the two are not as different as I had hoped." I said nothing in response. "Please do not imagine I think less of you after hearing your confession. On the contrary, I admire your honesty." He put his hand lightly on my cheek and left.

I remained standing for a moment after he departed, and placed my hand where his had rested on my cheek; it was as if I could still feel his touch. I dropped onto the nearest chair, wondering why I had spoken to him about such things. Why had I not written a tearful letter to Cécile instead? She would chastise me for falling in love with Philip. If only Ivy weren't so newly married, she might have been a good audience for my grievances. Funny that before her wedding I never minded telling her that I didn't love Philip. Now that she was happily settled, I must have feared she would judge me more harshly than she had as a single woman. I sighed. What Colin Hargreaves thought of me really did not matter in the least, and I did feel better for having told someone the truth.

Soon after Colin's departure, I went to the British Museum; I wanted to look at the Judgment of Paris vase. On my way through the Greco-Roman collection, I saw something that seemed familiar. When I stood before the case, I recognized it as the Praxiteles bust of Apollo. Philip must have succeeded in finding it, a realization that brought me no small measure of satisfaction. I looked at the card next to the object, expecting to see my husband's name listed as the donor. Instead a Thomas Barrett was given credit for the gift. Obviously this was not the bust to which Monsieur Fournier had referred; I must have been confused by the Frenchman's description.

I continued on to my favorite vase and stared at it for a considerable length of time, wishing that my husband were at my side. How I longed to hear his expert opinions on the artifacts surrounding me in the gallery. I vacillated between sorrow and a bittersweet joy at the thought that studying the things he loved could make me know him better than I did before his death. At the same time, I felt a terrible guilt for never having opened my heart to a man so deserving of my love. As I was contemplating my morose situation, Mr. Murray approached me.

"Lady Ashton! I am delighted to see that you have returned from France. Did you enjoy the City of Light?"

"Immensely, thank you. I'm so glad to see you, Mr. Murray."

"You look melancholy today," he said, hesitating slightly.

"I'm feeling rather sorry for poor Paris. I don't think that marrying Helen turned out to be much of a reward."

"I don't think he would have agreed. 'But let the business of our life be love: / These softer moments let delights employ, / And kind embraces snatch the hasty joy.'"

I continued for him. "'Not thus I loved thee, when from Sparta's shore / My forced, my willing heavenly prize I bore, / When first entranced in Cranae's isle I lay, Mix'd with thy soul, and all dissolved away!'" I smiled.

"Most impressive, Lady Ashton. You have embraced Pope."

"I have begun a study of several translations of Homer. Are you familiar with Matthew Arnold's lectures on the topic?"

"I was there when he delivered them at Oxford. Brilliant man."

"While I think it must be true that Homer can never be completely captured in translation, I am quite interested in whether an English poet can bring to us an experience-emotionally, that is-similar to that felt by the ancient Greeks upon hearing the poem in their native tongue."

"A question that, unfortunately, can never be adequately answered."

"Perhaps, but marvelous to contemplate, don't you think?" I stood silently for a moment, imagining an evening at home with Philip, discussing the topic. Could he have recited some of the poem for me in Greek? That would have been spectacular, although I would not have understood what he was saying. The thought of him doing so, particularly some of the more touching scenes between Hector and Andromache, was surprisingly titillating, and I had to willfully force my attention back to the present.

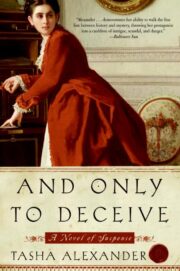

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.