After dinner I retired to the library and looked for something to read. The book I had carried on my honeymoon caught my eye, and I picked it up as I rang the bell for Davis.

"Would you bring me some port?" I tried to sound nonchalant and a bit sophisticated as I spoke.

"Port? Perhaps your ladyship would prefer sherry, if I may be so bold as to make a suggestion."

"I believe that my husband had a fine cellar, did he not?"

"Yes, madam."

"I see no reason that it should go to waste so long as I am in the house, and I've never cared for sherry."

"Which port would you like, madam?"

I looked at him searchingly. "I have no idea, Davis. Could you make a professional recommendation?"

"The '47 would be an excellent choice."

"That will be fine," I said, noticing that my solemn butler nearly smiled as he disappeared in search of the port. I looked at the book in my hand and wrinkled my nose. Lady Audley's Secret was not the book a young bride ought to have taken on her wedding trip, and my mother had forbidden me to pack it. I, of course, had not listened to her and began reading the story of the gorgeous Lucy almost as soon as our train pulled out of Victoria Station. If Philip disapproved, he did not show it, laughing instead when he saw what I was doing. He asked that I promise never to push him down a well, as Lucy did her husband to avoid being exposed as a bigamist. I remember assuring him that, as I had no intention of being married to more than one man, he had little to worry about, but that one never could be too careful around wells. I also noted with some satisfaction that he knew the plot and so must have read the book himself.

Davis returned with my port as I was lost in this memory, and I jumped a bit when I realized he was standing next to my chair.

"Thank you," I said, taking the glass he presented to me. I looked up at him and raised an eyebrow. "Do you think I shall like it?"

"The 1847 was the best vintage of the century, madam. It does not disappoint."

I took a small sip and sat for a moment. "Delicious." Now my butler did smile. "I saw that, Davis. You shall never be able to intimidate me again now that I know you smile." He clearly did not know how to respond. "I've been sitting here thinking about Lord Ashton. You worked for him for many years, didn't you?"

"I was in his father's household when Lord Ashton was a boy."

"I never considered Philip as having a childhood. Silly, isn't it?" No response from the proper Davis. "What was he like?"

"Always getting into trouble, Lady Ashton. Climbing the roof, scaling garden walls, digging huge, muddy holes. Used to mount what seemed to him at the time grand expeditions through the grounds of the estate."

"Then I am pleased to know that he was able to go on real expeditions as an adult."

"Yes, Lady Ashton." He stood silently for a moment. "Will that be all?"

I nodded, and he left me alone. I took another sip of the port, which really was good, and thought how enjoyable it was to behave in a way no one expected. I was trying to picture a smaller version of Philip tromping through the forests of his manor pretending to hunt for elephants when, for no apparent reason, I remembered the Praxiteles bust of Apollo that Monsieur Fournier had mentioned in Paris. Certain that it was not in the house, I went to Philip's desk and took out his journal, which I had put in one of the drawers shortly after it was sent to me from Africa. During our wedding trip, he had written in the book almost constantly and seemed to record many purchases that we made; I hoped to find such an entry for the bust.

Flipping through the leather-bound book, I came across sketch after sketch of various antiquities, but nothing that could be Apollo. Philip's technique was careless at best, but he managed to create a decent impression of the pieces he drew. Finally, toward the end of the volume, I found it: Apollo, hastily drawn, with "Paris?" written under him, with no indication that my husband had located, let alone purchased, the bust. I was about to return the journal to its drawer when I noticed a sentence written farther up on the page.

K lovelier than ever tonight. She still rarely looks at me when we speak, but am confident this will change. Paris had to convince Helen, after all, and I've no assistance from Aphrodite.

I decided to read more, going back to the beginning of the volume. Here I found Philip's version of our courtship and marriage, the plans for his safaris, comments on Homer, and general musings about the state of the British Empire. I laughed as I read his account of a dreadful evening spent with the Callums, none of the family attempting to hide their desire that he marry Emma, whose flirting had been particularly disgraceful that night. His lament on the pains of being a gentleman was particularly witty.

Soon came the story Colin had told me of the night Philip fell in love with me. Seeing on paper, in his own handwriting, the description of this event that meant so much to him and went largely unnoticed by me, I felt tears well in my eyes. He considered me his Helen. Of course I had to read more.

That he despised my mother surprised me; that this feeling began because she never left us alone in the drawing room before our marriage thrilled me. What would he have done had we been left alone? I loved the five pages he wrote planning what to say to my father when he asked for my hand, but not as much as those written in joyous rapture after I accepted his proposal.

I closed my eyes and tried with all my might to remember the details of that day. I know I had been arguing with my mother when he arrived and that she'd sat in a corner of the room embroidering, shooting menacing glances at me whenever she thought Philip wasn't looking. I realize now that she must have known he was going to propose; my father would have told her. She was probably terrified I would refuse him.

Distracted from my social duties by anger, I had wandered over to the window and stood in front of it looking into the street. Philip had walked up beside me.

"Emily, it cannot have escaped your notice that my feelings for you have grown daily at an astounding rate." I did not reply. "Never before have I known a woman with such spirit, such grace, and such beauty. When I think of the life I have before me, I cannot bear to imagine it without you." He took my hand and looked intently into my eyes. "Emily, will you do me the honor of being my wife?"

I was utterly shocked. Certainly he had called more often than other gentlemen of my acquaintance, but I had never noticed any particular attachment on his part; I obviously had none. Looking back, I realize that, my primary concern being avoiding marriage, I had never given much consideration to any of my suitors. As I looked at him, and at my mother peering anxiously toward us, I decided I would rather have him than her.

"Yes, Philip. I will marry you."

A bright smile spread across his face, and his light eyes sparkled. "You make me the happiest of men." He squeezed my hand. "May I kiss you?" I nodded and turned my cheek toward him; sitting in the library now, I remembered the feel of his lips against it and the warmth of his breath as he whispered, "I love you, Emily."

I thought I would go mad with desire when she presented that perfect ivory cheek for me to kiss. Had her blasted mother the courtesy to leave us alone for even a moment, I would have taken the opportunity to fully explore every inch of her rosebud lips. For that, I am afraid, I shall have to wait.

I closed the book and placed it on the table beside me. For a moment it felt as if I had been reading a particularly satisfactory novel in which the heroine had won the love of her hero. But I was the heroine, and the hero was dead, dead before I had even the remotest interest in him. I started to cry, softly at first, then with all-consuming sobs that I could hardly control. I went back to Philip's desk and opened the drawer from which I had taken his journal. In it I had also placed a photograph he had given to me shortly after our engagement. I pried it out of its elaborate frame, clutched it to my chest, and ran from the library, up the stairs to my bedroom. Meg rushed in from the dressing room, but I waved her away, falling asleep sometime later, still dressed and holding Philip's picture.

I should have spent the next morning leaving cards for my friends to alert them to my return to town, but I found the idea of doing so completely unappealing. Instead I took both breakfast and lunch in my room and did not ring for Meg to help me dress until nearly one o'clock in the afternoon. My head ached, and my eyes were red and swollen from crying. By two o'clock I had returned to my place in the library to resume reading Philip's journal. While I was in the midst of an admittedly tedious account of a grouse hunt, Davis entered the room.

"Mr. Colin Hargreaves to see you, madam. Shall I show him into the drawing room?"

I felt myself flush. "Tell him I'm not at home."

"Yes, madam." Davis turned to exit the room, and I called to stop him.

"Wait! I may as well see him. Bring him here, Davis. I prefer it to the drawing room."

I did not rise when Colin entered the library, and I barely glanced up to acknowledge his presence. "What a surprise, Mr. Hargreaves," I said coolly.

"I know I'm calling at a beastly hour, but I just saw Arthur Palmer at his club, and he told me what happened in Paris. Are you all right?"

"I'm fine. Thank you for your concern."

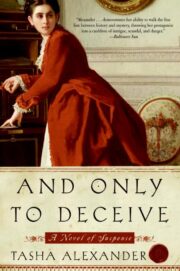

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.