Colin leaned back in his chair and stared at me. After some time I wondered if I should speak but found myself mesmerized by his dark eyes.

"Dance with me, Emily," he said quietly.

"What?"

"Dance with me."

"There's no music."

"I'll hum."

"I shouldn't. I'm in mourning."

"You're not dead," he said, standing, never taking his eyes off me. I gave him my hand, and we began to waltz in what little open space my sitting room offered. His grace surprised me, but not as much as the way my skin responded to his touch. The feeling of his hand on my waist caused me to breathe deeply, and when at last he released me, my hands trembled as I stumbled back to my seat.

"I think I should go," he said quietly.

"Yes, you're probably right," I agreed, not sure what to think. "But we haven't had dinner."

"I find that I am no longer hungry." His eyes shone with an intensity I had not seen before in anyone. He kissed my hand, his lips lingering longer than strictly necessary, and rushed from my rooms.

21 APRIL 1887

BERKELEY SQUARE, LONDON

Met a stunning girl at the Brandons' last night-Earl Bromley's daughter. Could not dance with her, as her card was already full. Dreaded encounter with Miss Huxley worse than expected. Will have words with Anne for having introduced me to her. Not only is she capable of speaking for fully a quarter of an hour without drawing breath (and on topics so boring that a mere three hours later I can't recall a single one), she has a way of clinging to a chap's arm that suggests she has no intention of ever letting go. Managed to eventually pry her away and sicced her on Hargreaves, who was unable to escape with as much ease as I did, not having the option of handing her off to a more handsome friend.

Have given thought to Lord Palmer's views on Hector v. Achilles and cannot agree. Hector is what man can strive to become; Achilles is that of which he can only dream. Who would not prefer the latter?

7

Soon thereafter I hired, on Renoir's recommendation, a drawing master called Jean Pontiero to instruct me twice a week. His mother was French, his father Italian, and the two countries seemed engaged in an endless battle for his soul. He preferred Italian food, French wine, Italian music, and French women. Once I learned to decipher his speech, an odd combination of the two languages, we got along famously. He did not judge my limited skills too harshly; in return, I included a pasta course at luncheon on the days he came to me.

"The view from your rooms is too French. We cannot work here any longer," he told me one day.

"I'm afraid we shall not be able to escape the French landscape, so we shall have to make do. Why don't we go sit in the park? It's quite warm today. A breeze would provide welcome relief." Monsieur Pontiero sniffed, packed up my drawing materials, and led me to the Louvre, where he set me to the task of sketching the first of ten paintings by Francisco Guardi showing Venice during a festival in the eighteenth century.

"I do have quite a keen interest in antiquities, Monsieur Pontiero. Perhaps I could draw something Roman instead? The sarcophagus reliefs in the Salle de Mécène?" He ignored me and began to lecture on the use of light in the painting before me. I sighed and began to sketch. Before long we were interrupted by a short, rather pale Englishman, whom my teacher quickly introduced as Aldwin Attewater.

"You would be interested in his work, Lady Ashton," Monsieur Pontiero said, smiling. "He copies antiquities."

"Do you really?" I asked. "I should love to see your work. Monsieur Pontiero won't let me draw anything but these landscapes, but I'd much rather sketch Greek vases."

"Black-or red-figure? Which do you prefer?" Mr. Attewater continued without waiting for me to answer. "I'm partial to the black myself. Of course, a mere sketch cannot do such a piece justice, which is why I prefer to reproduce it entirely."

"It also brings a much higher price that way," Monsieur Pontiero added. "Aldwin does a great deal of work for you English aristocrats who are willing to pay exorbitant prices for obvious fakes."

"My work is never obvious," Mr. Attewater replied. "It can be found in some of the world's best museums."

"Perhaps in your imagination, Aldwin. But look at my pupil's work. It is good, no?" Mr. Attewater looked over my shoulder at my uninspired rendition of poor Mr. Guardi's landscape and shrugged.

"Decent form, little passion. Move her to another gallery, Pontiero. If it's antiquities she likes, she should draw them. She is paying you, after all."

"Money, money, that's all you think about," Monsieur Pontiero jibed good-naturedly. "It is the art that matters, and she should start here."

"Your husband was the Viscount Ashton?" Mr. Attewater inquired.

"Yes, he died in Africa more than a year ago."

"I remember hearing that. Please accept my most sincere condolences. I'm certain that he is greatly missed in the art world. He was an excellent patron."

"Thank you, Mr. Attewater," I answered, and proceeded to change the subject. "Do you have a studio in Paris?"

"No, I prefer to work in London."

"The soot in the air helps to give his sculpture an ancient look," Monsieur Pontiero joked as his sharp eyes evaluated my sketch. "That's enough for today, Lady Ashton. I can see that you are too distracted to work." He sighed. "I imagine that Aldwin would be happy to lead us through the Ancient Sculpture collection. Perhaps he will allow you to choose the next work he plans to imitate."

"Maybe I will commission the work myself," I said, smiling. Monsieur Pontiero frowned.

"Your money would be better spent on Renoir or Sisley. At least their works are original."

"True," I began, "but if Mr. Attewater can produce an object of exquisite beauty, I'm not sure that his source of inspiration is of much consequence."

"Copying requires nothing more than mechanical skill," Monsieur Pontiero said. "The genius of the artist can never be duplicated. A work done by someone else's hand will always lack the spark of brilliance."

Mr. Attewater grinned. "I don't think you could tell the difference, my friend." They bickered back and forth well into the Greek collection, stopping only when I gasped at the sight of a particularly lovely sculpture of the goddess Artemis.

"You like this?" Mr. Attewater asked. I nodded. "What do you think, Pontiero?"

"It is exquisite."

"Does it contain a spark of brilliance?"

"Yes, it does," Monsieur Pontiero answered quickly. "Don't try to claim that it's one of yours. No one would believe you."

"I could reproduce it well, but it is not mine. Nonetheless, it is a copy, done by a Roman in the style of one done in bronze during the fourth century B.C. by a Greek called Leochares. Would you consider it a fake?"

"Hardly. It's an ancient piece."

"Ancient yes, but a copy of a sculpture more ancient." Mr. Attewater turned to me. "The Romans loved to copy Greek sculpture. Have you been to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens? There you will find real Greek statues."

"I shall have to go," I said, still looking at the beautifully carved Artemis.

"You'd prefer Rome," Monsieur Pontiero insisted.

Realizing he was about to embark on another of his monologues on the virtues of things Italian, I quickly interrupted. "Mr. Attewater, do you think our descendants will look at your copies in museums thousands of years from now, appreciating them as art in their own right, the way we do this statue?"

"Don't encourage him," Monsieur Pontiero scoffed. As we turned the corner, I was pleasantly surprised to see Colin Hargreaves seated on a bench at the far end of the gallery. He rose immediately when he saw me, and I introduced him to my companions. As always, he was exceedingly polite, and he asked to accompany us on our tour. Mr. Attewater, however, excused himself.

"I shall have to leave you now," he said. "I have an appointment I must keep. It has been most pleasant making your acquaintance, Lady Ashton."

Soon thereafter Monsieur Pontiero begged our leave to call on his next pupil. Colin took my drawing material from him, and we continued to walk through the museum.

"Please forgive me, Emily, but you should perhaps be a bit more discerning about the company you keep. Aldwin Attewater is not the sort of man with whom you ought to consort," he said in a soft but forceful voice.

"He seemed pleasant enough to me," I retorted, feeling my face grow red.

"Don't be naïve."

"I can't see why you should object to the acquaintance." It astonished me how quickly he was willing to attempt control over this small part of my life. Was this what came from dancing with him in such inappropriate circumstances?

"His profession precludes him from any position of honor."

"I did not think you were the type of man who would consider an artist dishonorable."

"My dear, he is not an artist. He is a forger."

"I don't see that he does anything wrong. Not everyone can afford originals, and I myself would enjoy having reproductions of some of the objects from museums."

"Then make use of the British Museum's casting services, Emily. There is a significant difference between a man who openly copies objects and one who produces forgeries. Mr. Attewater falls into the latter category, and you should not associate with such a man."

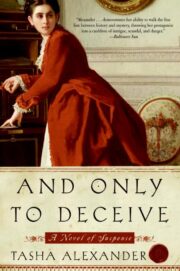

"And Only to Deceive" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "And Only to Deceive". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "And Only to Deceive" друзьям в соцсетях.