"I can readily believe that," Worth replied. "Does he anticipate that there will be any more fighting?"

"No, that is the best of all! He says that every French Corps but one was engaged in the battle, and the whole Army gone off in such a perfect rout and confusion he thinks it quite impossible for them to give battle again before the Allies reach Paris."

"Excellent news! I am much obliged to you for bringing it to me."

"I knew you would be glad to hear of it! You'll give my compliments to the ladies, and to poor Audley: I must be off, to catch the mail."

He bustled away, and Worth went upstairs to convey the tidings to his brother, whom he found lying quietly, with his hand in Barbara's. He told him what had passed, and had the satisfaction of seeing the Colonel's eyes regain a little of their sparkle. Lavisse's parting message evoked only a languid: "Poor devil! What a piece of work to make of nothing!" Worth, seeing that he was tired, went away, leaving him to the comfort of Barbara's presence.

The Duchess remained in the house all day, and the Duke, after trying in vain to obtain intelligence of George's fate, and calling at the Fishers' lodging to see Lucy (whom he declared to be a poor little dab of a thing, not worth looking at), took up his quarters in Lady Worth's salon. He was permitted to visit Audley for a few minutes before dinner, and took his hand in a strong hold, saying with a softened expression in his rather hard eyes: "Well, my boy, so you mean to have that vixen of mine, do you? You're deserving of a better fate, but if you're determined you may take her with my blessing."

"Thank you, sir," said the Colonel.

"And mind you keep her this time!" said his Grace. "I won't have her back on my hands again!"

His wife and granddaughter, judging that a very little of his bracing personality was enough for the Colonel in his present condition, then sent him away, and he went off to announce to Judith that, whatever he might think of George's choice, he was very well satisfied with Barbara's.

He bore his wife off to the Hotel de Belle Vue for dinner, promising, however, to permit of her returning to Worth's house later in the evening, to see how the Colonel went on. The fomentations had afforded some relief; there was no recurrence of the fever which had alarmed the ladies earlier in the day; and although the pulse was unsteady, the Duchess was able to inform her granddaughter before leaving the house that she had every expectation of the Colonel's speedy recovery. He was too weak to wish to indulge in much conversation, but he seemed to like to have Barbara near him. He lay mostly with closed eyes under a frowning brow, but if she moved from her chair it was seen that he was not asleep, for his eyes would open and follow her about the room. She soon found that her absence from his side made him restless, and so placed her chair close to the bed, and sat there, ready in an instant to bathe his brow with vinegar and water, to change the fomentations, or just to smile at him and take his hand.

It was not such a reunion as she had imagined. Her thoughts were confused. Harry's death lay at the back of them, like a bruise on her spirit. She had been prepared to hear that Charles had been killed, but she had never thought that he might come back to her so shattered that he could not take her in his arms, so weak that the smile, even, was an effort. There was much she had wanted to say to him, but it had not been said, and perhaps never would be. No drama attached to their reconciliation: it was quiet, tempered by sorrow.

Yet in spite of all, as she sat hour after hour beside Charles, a contentment grew in her and the vision of the conquering hero, who should have come riding gallantly back to her, faded from her mind. Reality was less romantic than her imaginings, but not less dear; and his feeble laugh and expostulation when she fed him with her grandmother's prescribed gruel were more precious to her than the most ardent love-making could have been.

Her dinner was sent up to her on a tray, and Judith and Worth sat down in the dining-parlour alone. They had not many minutes risen from the table when a knock fell on the street door, and an instant later George Alastair walked into the salon.

Judith exclaimed at the sight of him, for his appearance was shocking. His baggage not having reached Nivelles, where his brigade was bivouacked, he had not been able to change his tattered jacket and mud-splashed breeches. An epaulette had been shot off; a bandage was bound round his head; and he limped slightly from a sabre-cut on one leg. He looked pale, and his blood-shot eyes were heavy and red-rimmed from fatigue. He cut short Judith's greetings, saying curtly: "I came to enquire after Audley. Can I see him?"

"He is better, but very weak. But sit down! You look quite worn out, and you are wounded!"

"Oh, this!" He raised his hand to his head. "That will only spoil my beauty. Don't waste your pity on me, ma'am!"

"Have you dined?" Worth asked.

"Yes: at my wife's!" George replied, flinging the word at him. "I have also seen my grandparents, and have nothing left to do before rejoining my regiment except to thank Audley for his kind offices towards my wife."

"I am very sure he does not wish to be thanked. Oh, how relieved your grandparents must be to know you are safe, to have had the comfort of seeing you!"

He replied, with the flash of his sardonic smile: "Yes, extremely gratifying! It is wonderful what a slash across the brow can do for one. You will be happy to hear, ma'am, that my wife will remain in my grandparents' charge until such time as she may follow me to Paris. May I now see Audley?"

She looked doubtful. He saw it, and said rather harshly: "Oblige me in this, if you please! What I have to ask him will not take me long."

"To ask him?" she repeated.

"Yes, ma'am, to ask him! Audley saw my brother die, and I want to know where in that charnel-house to search for his body!"

She put out her hand impulsively. "Ah, poor boy! Of course you shall see him! Worth will take you up at once."

"Thank you," he said with a slight bow, and limped to the door, and opened it for Worth to lead the way out.

Judith was left to her own melancholy reflections, but these were interrupted in a very few minutes by yet another knock on the street door. She paid little heed, expecting merely to have a card brought in to her with kind enquiries after the state of Colonel Audley's health, but to her astonishment the butler very soon opened the door into the salon and announced the Duke of Wellington.

She started up immediately. The Duke came in, dressed in plain clothes, and shook hands, saying: "How do you do? I have come to see poor Audley. How does he go on?"

She was quite overpowered. She had never imagined that in the midst of the work in which he must be immersed he could find time to visit the Colonel. She had even doubted his sparing as much as a thought for his aide-de-camp. She could only say in a moved voice: "How kind this is in you! We think him a little better. He will be so happy to receive a visit from you!"

"Better, is he? That's right! Poor fellow, they tell me he has had to lose his arm."

She nodded, and, recollecting herself a little, began to congratulate him upon his great victory.

He stopped her at once, saying hastily: "Oh, do not congratulate me! I have lost all my dearest friends!"

She said in a subdued voice: "You must feel it, indeed!"

"I am quite heart-broken at the loss I have sustained," he replied, taking a quick turn about the room. "My friends, my poor soldiers - how many of them have I to regret! I have no feeling for the advantages we have acquired." He stopped, and said in a serious tone: "I have never fought such a battle, and I trust I shall never fight such another. War is a terrible evil, Lady Worth."

She could only throw him a speaking glance; her feelings threatened to overcome her; she was glad to see Worth come back into the room at that moment, and to be relieved of the necessity of answering the Duke. She sank down into a chair while Worth shook hands with his lordship. He, too, offered congratulations and comments on the nature of the engagement. The Duke replied in an animated tone: "Never did I see such a pounding-match! Both were what you boxers call gluttons. Napoleon did not manoeuvre at all. He just moved forward in the old style, in columns, and was driven off in the old style. The only difference was that he mixed cavalry with his infantry, and supported both with an enormous quantity of artillery."

"From what my brother has said, I collect that the French cavalry was very numerous?"

"By God, it was! I had the infantry for some time in squares, and we had the French cavalry walking about us as if they had been our own. I never saw the British infantry behave so well!"

"It has been a glorious action, sir."

"Yes, but the glory has been dearly bought. Indeed, the losses I have sustained have quite broken me down. But I must not stay: I have very little time at my disposal, as you may imagine. I came only to see Audley."

"I will take you to him at once, sir. Nothing, I am persuaded, will do him as much good as a visit from you."

"Oh, pooh! nonsense!" the Duke said, going with him to the door. "I shall be in a bad way without him, and the others whom I have lost, I can tell you!"

He followed Worth upstairs to Colonel Audley's room, only to be brought up short on the threshold by the sight of Lord George, standing by the bed. A frosty glare was bent on him; a snap was imminent; but Audley, startled by the sight of his Chief, still kept his wits about him, and said quickly: "Lord George Alastair, my lord, who has been sent in to have his wounds attended to, and has been kind enough to visit me on his way back to the brigade."

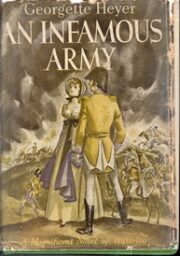

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.