She smiled. "I hope it may be true. He is not always so, I confess. To my mind he is excessively like his father in his dislike of strangers. Worth, of course, would have you believe quite otherwise. Sit down, and let me give you some coffee. Have you seen Worth yet?"

"Not a sign of him. Tell me all the news! What has been happening here? How do you go on?"

"But my dear Charles, I have no news! It is to you that we look for that. Don't you know that for weeks past we have been positively hanging upon your arrival, eagerly searching your wretchedly brief letters for the least grain of interesting intelligence?"

He looked surprised, and a little amused. "What in the world would you have me tell you? I had thought the deliberations of the Congress were pretty well known."

"Charles!" said her ladyship, in a despairing voice, "you have been at the very hub of the world, surrounded by Emperors and Statesmen, and you ask me what I would have you tell me!"

"Oh, I can tell you a deal about the Emperors," offered the Colonel. "Alexander, now, is - let us say - a trifle difficult."

He was interrupted. "Tell me immediately what you have been doing!" commanded Judith. "Dancing," he replied.

"Dancing!"

"And dining."

"You are most provoking. Are you pledged to secrecy? If so, of course I won't ask you any awkward questions."

"Not in the least," said the Colonel cheerfully. "Life —Vienna was one long ball. I have been devoting a neat part of my time to the quadrille. L'Ete, la Poule, : grande ronde - I have all the steps, I assure you."

"You must be a very odd sort of an aide-de-camp!" I:le remarked. "Does not the Duke object?"

"Object?" said the Colonel. "Of course not! He likes William Lennox would tell you that the excellence of pas de zephyr is the only thing that has more than once saved him from reprimand."

"But seriously, Charles -?"

"On my honour!"

She was quite dumbfounded by this unexpected light cast upon the proceedings at Vienna, but before she could express her astonishment her husband came into the room, and the subject was forgotten in the greeting between the brothers, and the exchange of questions.

"You have been travelling fast," the Earl said, as he presently took his seat at the table. "Stuart spoke of the Duke's still being in Vienna only the other day."

"Yes, shockingly fast. We even had to stop for lard to grease the wheels. But with such a shriek going up for the Beau from here, what did you expect?" said the Colonel, with a twinkle. "Anyone would imagine Boney to be only a day's march off from the noise you have been making."

The Earl smiled, but merely said: "Are you rejoining the Regiment, or do you remain on the Staff?"

"Oh, all of us old hands remain, except perhaps March, who will probably stay with the Prince of Orange. Lennox goes back to his regiment, of course. He is only a youngster, and the Beau wants his old officers with him. What about my horses, Worth? You had my letter?"

"Yes, and wrote immediately to England. Jackson has procured you three good hunters, and there is a bay mare I bought for you last week."

"Good!" said the Colonel. "I shall probably get forage allowance for four horses. Tell me how you have been going on here! Who's this fellow, Hudson Lowe, who knows all there is to be known about handling armies?"

"Oh, you've seen him already, have you? I suppose Vou know he is your Quartermaster-General? Whether he will deal with the Duke is a question yet to be decided."

"My dear fellow, it was decided within five minutes of his presenting himself this morning," said the Colonel, passing his cup and saucer to Lady Worth. "I left him instructing the Beau, and talking about his experience. Old Hookey was stiff as a poker, and glaring at him, with one of his crashing snubs just ripe to be delivered. I slipped away. Fremantle's on duty, poor devil."

"Crashing snubs? Is the Duke a bad-tempered man?" enquired Judith. "That must be a sad blow to us all."

"Oh no, I wouldn't call him bad-tempered!" replied the Colonel. "He gets peevish, you know - a trifle crusty, when things don't go just as he wishes. I wish they may get Murray back from America in time to take this fellow Lowe's place: we can't have him putting old hookey out every day of the week: comes too hard on the wretched staff."

Judith gave him back his cup and saucer. "But, Charles, this is shocking! You depict a cross, querulous person, and we have been expecting a demi-god."

"Demi-god! Well, so he is, the instant he goes into action," said the Colonel. He drank his coffee, and said, 'Who is here, Worth? Any troops arrived yet from England?"

"Very few. We have really only the remains of Graham's detachment still, the same that Orange has had under his command the whole winter. There are the 1st Guards, the Coldstream, and the 3rd Scots; all 2nd battalions. The 52nd is here, a part of the 95th - but you must know the regiments as well as I do! There's no English cavalry at all, only that of the German Legion."

The Colonel nodded. "They'll come."

"Under Combermere?"

"Oh, surely! We can't do without old Stapleton Cotton's long face among us. But tell me! who are all these schoolboys on the staff, and where did they spring from? Scarcely a name one knows on the Quartermaster-General's staff, or the Adjutant-General's either, for that matter!"

"I thought myself there were a number of remarkably inexperienced young gentlemen calling themselves Deputy-Assistants - but when the Duke takes a lad of fifteen into his family one is left to suppose he likes a staff just out of the nursery. By the by, I suppose you know you have arrived in time to assist at festivities at the Hotel de Ville tonight? There's to be a fete in honour of the King and Queen of the Netherlands. Does the Duke go?"

"Oh yes, we always go to fetes!" replied the Colonel. "What is it to be? Dancing, supper - the usual thing? That reminds me: I must have some new boots. Is there anyone in the town who can be trusted to make me a pair of hessians?"

This question led to a discussion of the shops in Brussels, and the more pressing needs of an officer on the Duke of Wellington's staff. These seemed to consist mostly of articles of wearing apparel suitable for galas, and Lady Worth was left presently to reflect on the incomprehensibility of the male sex, which, upon the eve of war, was apparently concerned solely with the price of silver lace, and the cut of a hessian boot.

The Colonel had declared his dress clothes to be worn to rags, but when he presented himself in readiness to set forth to the Hotel de Ville that evening his sister-in-law had no fault to find with his appearance beyond regretting, with a sigh, that his present occupation made the wearing of his hussar uniform ineligible. Nothing could have been better than the set of his coat across his shoulders, nothing more resplendent than his fringed sash, nothing more effulgent than his hessians with their swinging tassels. The Colonel was blessed with a good leg, and had nothing to fear from sheathing it in a skin-tight net pantaloon. His curling brown locks had been brushed into a state of pleasing disorder, known as the style au coup de vent; his whiskers were neatly trimmed; he carried his cocked hat under one arm; and altogether presented to his sister-in-law's critical gaze a very handsome picture.

That he was quite unaware of it naturally did not detract from his charm. Judith, observing him with a little complacency, decided that if Miss Devenish failed to succumb to the twinkle in the Colonel's open grey eyes, or to the attraction of his easy, frank manners, she must be hard indeed to please.

Miss Devenish would be present this evening, Judith having been at considerable pains to procure invitation tickets for her and for Mrs Fisher.

The Earl of Worth's small party arrived at the Hotel de Ville shortly after eight o'clock, to find a long line of carriages setting down their burdens one after another, and the interior of the building already teeming with guests. The ante-rooms were crowded, and (said Colonel Audley) as hot as any in Vienna; and her ladyship, having had her train of lilac crape twice trodden on, was very glad to pass into the ballroom. Here matters were a little better, the room being of huge proportions. Down one side of it were tall windows, with statues on pedestals set in each, while on the opposite side were corresponding embrasures, each one curtained, and emblazoned with the letter W in a scroll.

A great many of the guests were of Belgian or of Dutch nationality, but Lady Worth soon discovered English acquaintances among them, and was presently busy presenting Colonel Audley to those who had not yet met him, or recalling him to the remembrances of those who had. She did not perceive Miss Devenish in the room, but since she had taken up a position near the main entrance, she had little doubt of observing her arrival. Meanwhile, Colonel Audley remained beside her, and might have continued shaking hands, greeting old friends, and being made known to smiling strangers for any length of time, had not an interruption occurred which immediately attracted the attention of everyone present.

A pronounced stir was taking place in the ante-room a loud, whooping laugh was heard, and the next moment a well-made gentleman in a plain evening dress embellished with a number of Orders walked into the ballroom, escorted by the Mayor of Brussels, and a suite composed of senior officers in various glittering dress uniforms. The ribbon of the Garter relieved the severity of the gentleman's dress, but except for his carriage there was little to proclaim the military man. Beside the gilded splendour of a German Hussar, and the scarlet brilliance of an English Guardsman, he looked almost out of place. He had rather sparse, mouse-coloured hair, a little grizzled at the temples; a mouth pursed slightly in repose, but just now open in laughter; and a pair of chilly blue eyes set under strongly marked brows. The eyes must have immediately attracted attention had this not been inevitably claimed by his incredible nose. That high-bridged bony feature dominated his face and made it at once remarkable. It lent majesty to the countenance and terror to its owner's frown. It was a proud, masterful nose, the nose of one who would brook no interference, and permit few liberties. It was also a famous nose, and anyone beholding it would have had to be very dull-witted not to have realised at once that it belonged to the Duke of Wellington.

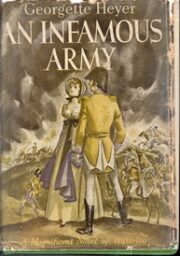

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.