"Stand fast, Ninety-fifth! We must not be beaten!" he shouted. "What will they say in England?"

A ragged cheer answered him; he re-formed the 79th himself, and directed them to fire upon the column that had driven them back, only withdrawing out of the heat of the battle when he saw that they stood firm.

The guns on both sides had ceased fire as the French and the British troops met, but in the valley smoke lay thick, and muskets spat and crackled. The French were hampered by the size of their own columns, but although the men of Picton's depleted division had checked their advance by the sheer ferocity of their charge, they could not hope to hold such overwhelming numbers at bay. West of the chaussee, the cuirassiers, having routed the Luneberg battalion, re-formed under the crest of the Allied position. Ignorant of what the reverse slope of the ground concealed, they charged up the bank, straight at Ompteda's men, hidden behind it. But the Germans had opened their ranks to permit the passage of cavalry through them. Before the cuirassiers had reached the crest, they heard the thunder of hooves above them, and the next instant the Household Brigade was upon them, led by Uxbridge himself, at the head of the 1st Life Guards.

With white crests, and horses' manes flying, the Life Guards came up at full gallop and crashed upon the cuirassiers in flank. The earth seemed to shudder beneath the shock. The Hyde Park soldiers never drew rein, but swept the cuirassiers from the bank, and across the hollow road in the irresistible impetus of their charge. Swords rang against the cuirasses; someone yelled above the turmoil: "Strike at the neck!" and the cuirassiers, already a little disorganised by their encounter with the German infantry, were flung back in fighting confusion. The Life Guards and the 1st Dragoon Guards hurled their left flank past the walls of La Haye Sainte in complete disorder, and scattered Quiot's brigade of infantry assailing the farm. The right flank of the cuirassiers swerved sharply to the east, and plunged down on to the chaussee to escape from the fury of six-foot men on huge horses, who seemed to have no idea of charging at anything slower than a full gallop. Not more than half their number had crossed the chaussee to the valley where Donzelot was driving his congested ranks against Kempt's brigade, when the rest of the Household Cavalry, coming up on the left of the Life Guards, fell upon them in hard-riding squadrons, and crumpled them up. The abattis, so painstakingly built up by the riflemen, was scattered in an instant; the cuirassiers were cut down in hundreds, and the Dragoon Guards rode over them to charge full tilt into the column of French infantry pressing Kempt's men back.

At the same moment, an aide-de-camp rode up from the rear to the hedge beyond which Pack's Highlanders were fighting fiercely with the men of Marcognet's division. For one moment he stood there, closely observing the state of the battle raging in the valley; then he took off his cocked hat and waved it forwards.

There was yell of: "Now then, Scots Greys!" and the next instant the whole of the Union Brigade came thundering up the reverse slope. The French, disordered through their inability to deploy their enormous column before the Highlanders charged them, appalled hardly more by the fury of the kilted devils who rushed on them than by the unearthly music of the pipes playing Scots, Wha' Hae in the hell of blood and smoke and clashing arms that filled the valley, heard the cavalry thundering towards them, and looked up to see great grey horses clearing the hedge above them.

They fell back. In the valley, officers were shouting to the Gordons to wheel back by sections to let the cavalry pass through. The Scots Greys tightened their grips, and came slipping and scrambling down the bank shouting: "Hurrah, Ninety-second! Scotland for ever!" as they caught sight of the red-feathered bonnets in the press and the smoke below.

Greys, Royals, and Inniskillings, riding almost abreast, poured over the hedge and down into the seething valley. The Gordons were yelling: "Go at them, the Greys! Scotland for ever!" and snatching at stirrup-leathers as the Greys rode through them, so that they too were borne forwards in this terrific charge. Somewhere, lost in the smoke, a pipe-major was coolly playing, Hey, Johnny Cope, are ye waukin' yet? while all around sounded screams, shouts, musketry fire, and the clash of steel.

Many of the horses and their riders were brought down by musketballs or the desperate thrust of bayonets, but the cavalry charge had caught Marcognet's column unawares and in confusion. The Union Brigade rode over the column, lopping off heads with their sabres, while the Gordons, who had been carried forward with them, did deadly work with the bayonet.

To the right, where Donzelot's men had fought their way through Kempt's thin lines to the crest of the position, the Royal Dragoons, unchecked by the frontal fire that met them, charged straight for the leading column of the division. The column faced about and tried to retreat over the hedge, but there was no time to get to safety before the Royals were in their midst, their sabres busy and their horses squealing, biting, and striking out with their iron-shod forefeet. Between the Greys and the Royals, the Inniskillings, with their blood-curdling howl, broke through Donzelot's rear brigades. As the Royals, capturing the Eagle, charged on over the slaughtered leading column to the supporting ones behind it, and the Greys rode down Marcognet's men, the French, utterly demoralised, began throwing down their arms and crying for quarter.

The Household Brigade, having broken the cuirassiers and smashed their way through Bourgeois' rear column, dashed on, deaf to the trumpets sounding the Rally and to the voices of Uxbridge and Lord Edward trying to recall them, up the slope towards the great French battery on the ridge. The Union Brigade, leaving behind them a plain strewn with dead and wounded, and prisoners being herded to the rear, charged after the Household troops, and galloped up the slope to within half-carbine shot of where Napoleon himself was standing, by the farm of La Belle Alliance.

A colonel of the Greys shouted: "Charge! Charge the guns!" and his men dashed after him, through a storm of shot, laming the horses, cutting the traces, and sabring the gunners.

The cavalry charge had put almost all Count D'Erlon's Corps d'Arm&e to rout, but it had been carried too far. Ahead, solid columns of infantry were advancing from the French rear; and behind, from either flank, lancers and cuirassiers were riding to cut off the retreat.

A voice cried: "Royals, form on me!" The Greys and the Inniskillings on the ridge, their horses blown, themselves badly mauled, looked round in vain for their officers, and tried to reform to meet the onset of the French cavalry. The Colonel who had led them in the charge towards the battery had been seen riding among the guns like a maniac, with both hands lopped off at the wrists, and his reins held between his teeth; but he had fallen, and a dozen others with him. A sergeant called out: "Come on, lads! That's the road home!" and the gallant little band rode straight for the oncoming cavalry that separated it from its own lines.

A pitiful remnant broke through. On the Allied left wing, Vandeleur flung forward his light dragoons to cover the retreat. They cheered the heavies as they passed them, caught the lancers in flank, and drove them back in disorder. The survivors of the Union Brigade reached the shelter of their own lines, having pierced three columns, captured two Eagles, wrecked fifteen guns, put twenty-five more temporarily out of action, and taken nearly three thousand prisoners.

Chapter Twenty-Three

The great infantry attack on the Allied left centre had failed. The Household Brigade had repulsed Quiot from La Haye Sainte; Bourgeois and Donzelot had been forced to retreat with heavy loss; and Marcognet's division was shattered. The remaining column, led by Durutte, had had more success, but was forced to retire in the general retreat. Durutte had advanced against Papelotte, and had driven Prince Bernhard's Nassauers out of the village. These re-formed, and in their turn drove out the French. Vandeleur's brigade of light cavalry charged the column, and it drew off, but in good order.

On the Allied side the losses were enormous. Kempt and Pack could no longer hope to hold the line, and Lambert's brigade was ordered up from Mont St Jean to reinforce them. The Union Brigade had been cut to pieces; the Household troops were reduced to a few squadrons. Of the generals, Picton had been killed outright in the first charge; Sir William Ponsonby, leading the Union Brigade on a hack horse, was lying dead on the field with his aide-de-camp beside him; and Pack and Kempt, on whom the command of the 5th Division had devolved, were wounded. Lord Edward Somerset, unhorsed, his hat gone, the lap of his coat torn off, got to his own lines miraculously unscathed.

Lord Uxbridge, who, when the Life Guards and the Dragoon Guards ignored the Rally, had ridden back to bring up the Blues in support, only to find that they had galloped into first line before ever they had passed La Haye Sainte, listened in contemptuous silence to the congratulations of the Duke's suite upon the brilliant success of his charge. He turned away, remarking to Seymour, with a disdainful curve to the mouth: "That Troupe doree seems to think the battle is over. But had I, when I sounded the Rally, found only four well-formed squadrons coming on at an easy trot, we should have captured a score of guns and avoided these shocking losses. Well! I deviated from my own principle: the carriere once begun the leader is no better than any other man. I should have placed myself at the head of the second line."

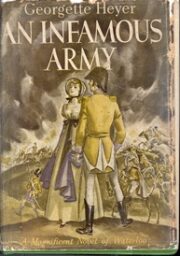

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.