"Oh, quite so!" said Lord Arthur hastily. "I daresay there's nothing in it at all."

Chapter Fifteen

Leaving Wellington's Headquarters, Colonel Audley made his way across the Park to Vidal's house. Barbara was not in, and as the butler was unable to tell Colonel Audley where she was to be found, he went back into the Park, and walked slowly through it in the direction of the Rue de Belle Vue. He was not rewarded by any glimpse of Barbara, but on reaching his brother's house found Lady Taverner sitting with Judith, and indulging in a fit of weeping. He withdrew, nor did Judith try to detain him. But when Harriet had left the house he went back to the salon, and demanded an explanation of her grief.

Judith was reluctant to tell him the whole, but after listening for some moments to her glib account of nervous spasms, ridiculous fancies, and depression of spirits, he interrupted her with a request to be told the truth. She was obliged to confess that Peregrine's infatuation with Barbara was the cause of Harriet's tears. She described first the incident in the park ,feeling that it was only fair that he should know what had prompted Barbara's outrageous conduct.

He listened to her with a gradually darkening brow. "Do you expect me to believe that Bab is encouraging Peregrine's advances out of spite?" he asked.

"I should not have used that word. Revenge, let us say."

"Revenge! We need not employ the language of the theatre, I suppose! What more have you to tell me! I imagine there must be more, since I understand that the whole town is talking of the affair."

"It is very unfortunate. I blame Harriet for the rest. She quarrelled with Perry, and I have no doubt made him angry and defiant. You know what a boy he is!"

He replied sternly: "He is not such a boy but that he knew very well what he was about when he made advances to my promised wife!"

"It was very bad," she acknowledged. "But, though I do not like to say this to you, Charles, I believe it way not all his fault."

"No! That is evident!" he returned. He walked over to the window and stood staring out. After a slight pause, he said in a quieter voice: "Well, now for the rest, if you please."

"I do not like the office of talebearer."

He gave a short laugh. "You need not be squeamish. Judith. I suppose I have only to listen to what the gossips are saying to learn the whole of it."

"You would hear a garbled version, I assure you."

"Then you had better let me hear the true version."

"I only know what Harriet has told me. I am persuaded that had it not been for her conduct, which you know, was very bad, the affair would never have gone beyond that one unfortunate evening in the suburbs. But she cut Lady Barbara in the rudest way! That began it. I could see how angry Lady Barbara was indeed, I didn't blame her. I hoped her anger would cool. I think it might have - I think, in fact, it had cooled. Then came the Duchess of Richmond's party. I saw Lady Barbara look round the hall when she arrived, and I can vouch for her having made no sign to Perry. I don't think she gave him as much as a civil bow. There was a lull in the conversation; everyone was staring at Lady Barbara - you know how they do! - and Harriet made a remark there could be no misunderstanding. It was stupid and ill-bred: I know I felt ready to sink. She then told Perry that she wished to remove into the salon, saying that the hall was too hot for her. Lady Barbara could not but hear. It was said, moreover, in such a tone as to leave no room for anyone to mistake its meaning."

She paused. The Colonel had turned away from the window, and was attending to her with a look of interest. He was still frowning, but not so heavily, and at the back of his eyes she fancied she could perceive the suspicion of a smile. "Go on!" he said.

She laughed. "Worth said that in its way it was perfect. I suppose it was."

"He did, did he? What happened?"

"Well, Lady Barbara just took Perry away from Harriet. It is of no use to ask me how, for I don't know. It may sound absurd, but I saw it with my own eyes, I am ready to swear she neither moved nor spoke.

She looked at him, and smiled, and he walked right across the room to her side."

He was now openly laughing. "Is that all? Of course.. it was very bad of Bab, but I think Harriet deserved it. It must have been sublime!"

"Yes," she agreed, but with rather a sober face.

He regarded her intently. "Is there more, Judith?"

"I am afraid there is. As I told you, Harriett quarrelled with Perry. You remember, Charles, that you were in Ghent. It seems that Perry rode out with Lady Barbara before breakfast next morning. I believe she is in the habit of riding in the Allee Verte every morning."

"You need not tell me that," he interrupted. "I know. She appointed Perry to ride with her?"

"So I understand. He made no secret of it, which makes me feel that he cannot have intended the least harm. But Harriet was suffering from such an irritation of nerves that she allowed her jealousy to overcome her good sense; they quarrelled; Perry left the house it anger; and, I dare say out of sheer defiance, joined the party Lady Barbara had got together to picnic in the country that evening. The gossip arose out of being the one chosen to drive with her in her phaeton. I am afraid he has done little to allay suspicion since. It is all such a stupid piece of nonsense, but oh, Charles, if you would but use your influence with Lady Barbara. Harriet is in despair, and indeed it is very disagreeable. to say the least of it, to have such a scandal in our midst!"

"Disagreeable!" he exclaimed. "It is a damnable piece of work!" He checked himself, and continued in a more moderate tone: "I beg your pardon, but you will agree that I have reason to feel this strongly. Is Peregrine with Bab now?"

"I do not know, but I judge it to be very probable." She saw him compress his lips, and added: "I think if you were to speak to Lady Barbara -"

"I shall speak to Barbara in good time, but my present business is with Peregrine."

She could not help feeling a little alarmed. He spoke in a grim voice which she had never heard before, and when she stole a glance at his face there was nothing in his expression to reassure her. She said falteringly: "You will do what is right, I am sure."

He glanced down at her, and seeing how anxiously she was looking at him, said with a faint smile, but with a touch of impatience: "My dear Judith, do you suppose I am going to run Peregrine through, or what?"

She lowered her eyes in a little confusion. "Oh! of course not! What an absurd notion! But what do you mean to do?"

"Put an end to this nauseating business," he replied.

"Oh, if you could! Such affairs may so easily lead to disaster!"

"Very easily."

She sighed, and said rather doubtfully: "Do you think that it will answer? I would have spoke to Perry myself, only that I feared to do more harm than good. When he gets these headstrong fits the least hint of oposition seems to make him worse. I begged Worth to intervene, but he declined doing it, and I daresay he was right."

"Worth!" he said. "No, it is not for him to speak to Peregrine. I am the one who is concerned in this, and what I have to say to Peregrine I can assure you he will pay heed to!" He glanced at the clock over the fireplace. and added: "I am going to call at his house now. Don't look so anxious, there is not the least need."

She stretched out her hand to him. "If I look anxious it is on your account. Dear Charles, I am so sorry this should have happened! Don't let it vex you: it was all mischief, nothing else!"

He grasped her hand for a moment, and said in a low voice: "Unpleasant mischief.It is the fault of that wretched up-bringing! Sometimes I fear - But the heart is unspoiled. Try to believe that: I know it!"

She could only press his fingers understandingly. He held her hand an instant longer, then, with a brief smile, let it go and walked out of the room.

Peregrine was not to be found at his house, but Colonel Audley sent up his card to Lady Taverner, and was presently admitted into her salon.

She received him with evident agitation. She looked frightened, and greeted him with nervous breathlessness, trying to seem at ease, but failing miserably.

He shook hands with her, and put her out of her agony of uncertainty by coming straight to the point. "Lady Taverner, we are old friends," he said in his pleasant way. "You need not be afraid to trust me, and I need not, I know, fear to be frank with you. I have come about this nonsensical affair of Peregrine's. Shall we sit down and talk it over sensibly together?"

She said faintly: "Oh! How can I -You - I do not know how to -"

"You will agree that I am concerned in it as much as you are," he said. "Judith has been telling me the whole. What a tangle it is! And all arising out of my stupidity in allowing Peregrine to be my deputy that evening! Can you forgive me?"

She sank down upon the sofa, averting her face. "I'm sure you never dreamed - Judith says it is my own fault, that I brought it on myself by my folly!"

"I think the hardest thing of all is to be wise in our dealings with the people we love," he said. "I know I have found it so."

She ventured to turn her head towards him. "Perhaps I was a fool. Judith will have told you that I was rude and ill-bred. It is true! I do not know what can have possessed me, only when she came up to me, so beautiful, and - oh, I cannot explain! I am sorry: this is very uncomfortable for you!"

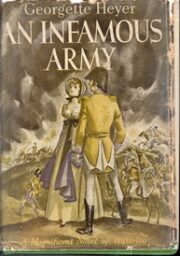

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.