"If he said it to you it is a sure sign that his affections are not seriously engaged. If I were you I would take him back to Yorkshire and forget the whole affair."

"He won't go!" said Harriet, burying her face in her handkerchief. "He said so. We have had a terrible quarrel! I told him -"

Judith flung up her hands. "I can readily imagine what you told him! Perry is nothing but a heedless boy! I daresay he never dreamed of being in love with Lady Barbara. He thought of her as Charles's fiancée, he found her good company, he admired her beauty. And what must you do but put it into his head to fall in love with her! Oh, Harriet, Harriet, what a piece of work you have made of it!"

This was poor comfort for an afflicted lady, and provoked Harriet to renewed floods of tears. It was some time before she was able to regain any degree of calm, and even when her tears were dried Judith saw that no advice would be attended to until she had had time to recover from the ill-effects of her first quarrel with Peregrine. She persuaded her to take the air in an open carriage, and sat beside her during the drive, endeavouring to engage her interest in everyday topics. Nothing would do, however. Harriet sat with her veil down; declined noticing the flowers in the Park, the barges on the canal, or the pigeons on the steps of St Gudule; and was morbidly convinced that she was an object of pity and amusement to every passer-by who bowed a civil greeting. Judith was out of all patience long before the drive came to an end, and when she at last set Harriet down at the door of her lodging her sympathies lay so much with Peregrine that she was able to wave to him, when she caught sight of him presently, with a perfectly good will.

Such feelings were not of long duration. A second note from Harriet, received during the evening, informed her that Peregrine had returned home only to change his dress, and had gone out again without having made the least attempt to see his wife. Harriet declared herself to be in no doubt of his destination, and ended an incoherent and blistered letter by the expression of a strong wish to go home to her mama.

By the following day every suspicion had been confirmed: Peregrine had indeed been in Barbara's company. He had made one of a party bound for the neighbourhood of Hal, and had picnicked there on the banks of the Senne, returning home only with the dawn. To make matters worse, it had been he whom Barbara had chosen to escort her in her phaeton. Every gossiping tongue in Brussels was wagging; Harriet had received no less than five morning calls from thoughtful acquaintances who feared she might not have heard the news; and more than one matron had felt it to be her duty to warn Judith of her young brother's infatuation. Loyalty compelled Judith to make light of the affair, but soon her patience had become so worn that the only person towards whom her sympathy continued to be extended was Charles Audley.

He had not made one of the picnic party, and from the circumstance of his being employed by the Duke all the following morning it was some time before any echo of the gossip came to his ears. It reached him in the end through the agency of Sir Colin Campbell, the Commandant, who, not supposing him to be within earshot, said in his terse fashion to Gordon: "The news is all over town that that young woman of Audley's is breaking up the Taverner household."

"Good God, Sir, you don't mean it? Confound her, why can't she give Charles a little peace?"

Sir Colin grunted. "He'll be well rid of her," he said sourly. He turned, and saw Colonel Audley standing -perfectly still in the doorway. "The devil!" he ejaculated. "Well, you were not meant to hear, but since you have heard there's no helping it now. I'm away to see the Mayor."

Colonel Audley stood aside to allow him to pass out of the room, and then shut the door, and said quietly: "What's all this nonsense, Gordon?"

"My dear fellow, I don't know! Some cock-and-bull story old Campbell has picked up - probably from a Belgian, which would account for its being thoroughly garbled. Did I tell you that I found him bewildering the maitre d'hotel the other day over the correct way to lay a table? He kept on saying: 'Beefsteak, venez ici: Petty-patties, allez la!' till the poor man thought he was quite mad."

"Yes, you told me," replied Audley. "What is the news that is all over town?"

A glance at his face convinced Sir Alexander that evasion would not answer. He said, therefore, in a perfectly natural tone: "Well, you came in before I had time to ask any questions, but according to Campbell there's a rumour afloat that Taverner is making a fool of himself over Lady Bab."

"That doesn't seem to me any reason for accusing Bab of breaking up his household."

"None at all. But you know what people are."

"There's not a word of truth in it, Gordon."

"No."

There was a note of constraint in Gordon's voice which Audley was quick to hear. He looked sharply across at his friend, and read concern in his face, and suddenly said: "Oh, for God's sake - ! You needn't look like that! The very notion of such a thing is absurd!"

"Steady!" Gordon said. "It isn't my scandal."

"I know. I'm sorry. But I am sick to death of this town, and the gossip that goes on in it!" He sighed, and walked over to the desk, and laid some papers down on it. "You had much better tell me, Gordon. What is it now? I suppose you've heard talk?"

"Charles, dear boy, if I had I wouldn't bring it to you," replied Gordon. "I don't know what's being said, or care."

Colonel Audley glanced up and suddenly laughed. "Damn you, don't look so sorry for me! What a set you are! I'm the happiest man on earth!"

"Famous! If you are, stop wearing a worried frown, and try going to bed at night for a change." He lounged over to where Audley was standing, and gripped his shoulder, slightly shaking him. "Damned fool! Oh, you damned fool!"

"I daresay. Thank God, I'm not a fat fool, however!"

He drove a friendly punch at Gordon's ribs. "Layers of it. What you need is a nice, hard campaign, my boy, to take some of it off."

"Not a chance of it! We'll be in Paris a month from now. I'll give you a dinner at a little restaurant I know there they have the best Chambertin in the whole city."

"I shall hold you to that. Where is it? I thought I knew all the restaurants in Paris."

"Ah, you don't know this one! It's in the Rue de - Rue de - confound it, I forget the name of the street, but I shall find it quick enough. Hallo, here's the Green Baby!"

Lieutenant the Honourable George Cathcart, lately enrolled as an extra aide-de-camp, had come into the room. He owed his appointment to the Duke's friendship with his father, the British Ambassador at St Petersburg. He was only twenty-one years old, but during the period of Lord Cathcart's office as military commissioner to the Russian Army, he had acted as his aide-de-camp, and was able to reply now with dignity "I am not a green baby. I have seen eight general actions. And what's more," he added, as the two elder men laughed, "Napoleon commanded in them all!"

"One to you, infant," said Audley. "You have us on the hip."

"Do you think Boney knows he's with us?" said Gordon anxiously.

"Oh, not a doubt of it! He has his spies everywhere."

"Ah, then, that accounts for him holding off so long: He's frightened."

"Oh, you - you -!" Cathcart sought for a word sufficiently opprobrious to describe Sir Alexander, and could find none.

"Never mind!" said Gordon. "You won't be the babe much longer. We shall have his Royal Highness the Hereditary Prince of Nassau-Usingen with us soon. and we understand he's only nineteen."

"He can't be of any use. What the devil do we want him for?"

"We don't want him. We're just having him to lend tone to the family. Charles, are you going to Braine-le-Comte?"

"Yes, I'm waiting for the letters now. Any message?"

"No. Such is my nobility of character that I'll go in your stead. Now, don't overwhelm me with thanks: Sacrifice is a pleasure to me."

"I shan't. Pure self-interest gleams in your eye. Give my compliments to Slender Billy, and don't outstay your welcome. Is he giving a dinner party?"

"This ingratitude! How can you, Charles?" Gordon said.

"Easily. I shall laugh if you find the Duke has labelled the despatch 'Quick'."

"If there's any 'Quick' about it, you shall take it," promised Gordon.

"Not I! You offered to go, and you shall go. Young Mr Cathcart will enlarge his military experience by kicking his heels here; and Colonel Audley will seize a well-earned rest from his arduous duties." He pciked up his hat from a chair as he spoke, and witt a wave to Gordon and an encouraging nod to Cathcart, made for the door. There he collided with a very burly young man, whose bulk almost filled the aparture. He recoiled, and said promptly: "In the very nick of time! Captain Lord Arthur Hill will be in reserve. Don't be shy, Hill! Come in! You know Gordon likes to have you near him: it's the only time he looks thin."

Lord Arthur, who enjoyed the reputation of being the fattest officer in the Army, received this welcome with his usual placid grin, and remarked as the Colonel disappeared down the stairs: "You fellows are always funning. What's happened to put Audley in such spirits? I suppose he hasn't heard the latest scandal? They tell me -"

"Oh, never mind what they tell you!" Gordon said, with such unaccustomed sharpness that Lord Arthur blinked in surprise. He added more gently: "I'm sorry, but Audley's a friend of mine, and I don't propose to discuss his affairs or to listen to the latest scandal about his fiancée. It's probably grossly exaggerated in any case."

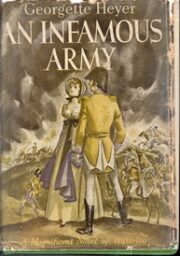

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.