She glanced at Barbara, and was not surprised to see her green eyes as hard as two bits of glass. A little colour had stolen into her cheeks; her lips were just parted over her clenched teeth. If ever anyone was in a rage she was in one now, thought Judith. She looked ripe for murder, and really one could not blame her.

"That," said Barbara, "was neither wise nor wellbred Lady Taverner. Convey my compliments to her, if you please, and inform her that I shall endeavour not to disappoint her very evident expectations."

"She is extremely foolish, and I beg you will not notice her rudeness!" said Judith. "No one regards what you so rightly call the nonsensical story which current."

"How simple of you to think so! The story must now be implicitly believed. By tomorrow I shall be credited with a sin I haven't committed, which touches my pride, you know. I always give the scandalmongers food for their gossip."

"To give them food in this case would be to behave-as foolishly as my sister-in-law," said Judith, trying to speak pleasantly.

"Oh, I have my reputation to consider!" Barbara retorted. "I make trouble wherever I go: haven't you been told so?"

"I have tried not to believe it."

"A mistake! I am quite as black as I am painted. I assure you. But I am keeping you from Lady Taverner. Go after her - and don't forget my message!"

Chapter Fourteen

Judith did not go after her sister-in-law. She had very little hope of inducing Harriet to apologise, nor, upon reflection, did she feel inclined to make the attempt. She could not think Barbara blameless in the affair. However well she might have behaved in extending an olive branch, the original fault was one for which Judith could find little excuse. If Barbara wanted to dine in the suburbs (which, in itself, was a foolish whim) she might as well have chosen an evening when Charles could have been free to have escorted her.

Judith acquitted her of wanting to make mischief. It had all been the result of thoughtlessness, and had Harriet behaved like a sensible woman nothing more would have come of it. But Harriet had chosen to do the one thing that would lend colour to whatever gossip was afoot, and had besides made an enemy of a dangerous young woman. It still made Judith blush to think of the scene. In Barbara's place she would, she acknowledged, have been angry enough to have boxed Harriet's ears. But such sudden anger was usually short-lived. She hoped that a period of calm reflection would give Barbara's thoughts a more proper direction, and determined to say nothing of the occurrence Charles.

She heard her name spoken, and came out of reverie to find herself confronting Lord Fitzroy Somerset, who, with his elder brother, Lord Edward and their nephew, Henry Somerset, was strolling along the path down which her unconscious footsteps had taken her.

Greetings and handshakes followed. Judith was acquainted with Lord Edward, but Lieutenant Somerset, who was acting as his uncle's aide-de-camp had to be presented to her. Lord Edward had only lately arrived from England, to command the brigade of Household Cavalry. He was twelve years Lord Fitzroy's senior, and did not much resemble him. Fitzroy was fair, with an open brow, and very regular features. Lord Edward was harsh-featured and dark with deep lines running down from the corners of his jutting nose and his close-lipped mouth, and two clefts between his brows. His eyes were rather hard, and he did not look to have that sweetness of disposition which made his brother universally beloved; but he was quite unaffected, laughed and talked a great deal, and seemed perfectly ready to be agreeable. Judith enquirerd after his wife; he had not brought her to the Netherlands; he thought - saving Lady Worth's presence! - that the seat of an approaching war way not the place for females.

"Your husband is not engaged in the operations, and so the case is different," he said. "But I assure you, the women who would persist in following the Army in Spain were at times a real hindrance to us. Nothing could stop them! Very courageous, you will say, and I won't deny it, but they were the devil to deal with on the march, choking the roads with their gear!"

She smiled, and agreed that it must have been so. She had turned to retrace her steps with the Somersets, and as the path was not broad enough to allow of their walking abreast, Lord Fitzroy and his nephew had gone ahead. She indicated Fitzroy with a nod, and remarked that his brother must not speak so in his hearing.

"Oh, Fizroy knows what I think!" replied Lord Edward. "However, he is not an old married man like me, so he must be pardoned. Not but what I think it a great piece of folly on his part. Of course, you know Lady Fitzroy has lately been confined?"

"Indeed I do, and I am one of her daughter's chief admirers!"

"I daresay. A nice thing it would have been had she been obliged to remove in a hurry!"

"Depend upon it, had there been any fear of that her uncle must have known of it, and she could have retired without the least hurry to Antwerp. He does not appear to share your prejudice against us poor females!"

"The Duke! No, that he does not!" replied Lord Edward, laughing. "But, come, enough of the whole subject, or I can see I shall be quite out of favour with you! I understand I have to congratulate Audley upon his engagement?"

She acknowledged it, but briefly. He said in his downright way: "I don't know how you may regard the matter, but I should have said Audley was too good man for Bab Childe."

She found herself so much in accordance with the opinion that she was unable to forbear giving him very speaking glance.

"Just so," he said, with a nod. "I have known the whole family for years - got one of them in my brigade now: handsome young devil, up to no good - and shouldn't care to be connected with any of them. As for Audley, he's the last man in the world I should havt expected to be caught by Bab's tricks. Great pity though I shouldn't say so to you, I suppose."

"Lady Barbara is very beautiful," Judith replied, with a certain amount of reserve.

He gave a somewhat scornful grunt, and said no more. They had reached one of the gates opening on to the Rue Royale at this time, and Lord Edward, who was on his way to Headquarters, took his leave of Judith, and strode off up the road with his nephew.

Lord Fitzroy gave Judith his arm. He had to pay a call at the Hotel de Belle Vue, and was thus able to accompany her to her door. They walked in that direction through the Park, talking companionably of Lady Fitzroy's progress, of the infant daughter's first airing, and other such mild topics, until presently they were joined by Sir Alexander Gordon, very smart in a new coat and sash, on which Lord Fitzroy immediately quizzed him.

Judith listened, smiling, to the interchange of friendly raillery, occasionally being appealed to by one of them, to give her support to some outrageous libel on the other.

"Gordon," Fitzroy informed her, "is one of our dressier colleagues. He has seventeen pairs of boots. That's called upholding the honour of the family."

"One of Fitzroy's grosser lies, Lady Worth. Now, the really dressy member of the family is Charles."

"He has the excuse of being a hussar. They can't help being dressy, Lady Worth. However, the strain of trying to procure a sufficiency of silver lace in Spain wore the poor fellow out, and in the end he was quite thankful to be taken into the family. I say, Gordon, why didn't you join a hussar regiment? Was it because you were too fat?"

"A dignified silence," Gordon told Judith, "is the only weapon to use against vulgar persons."

"Very true. It is all jealousy, I daresay. I feel sure you could set off a hussar uniform to admiration."

"Fill it out, don't you mean?" enquired Fitzroy.

Sir Alexander was diverted from his purpose of retaliating in kind by catching sight of Barbara Childe between two riflemen. "When does that marriage take place, Lady Worth?" he asked.

"The date is not fixed."

"There's hope yet, then. That's Johnny Kincaid with her - the tall lanky one on her right. Perhaps he'll cut Charles out. Very charming fellow, Kincaid."

Fitzroy shook his head. "No chance of that. Kincaid loves Juana Smith - or so I've always fancied."

Judith said: "Is that how you feel, Sir Alexander? About Charles's engagement, I mean?"

"I beg pardon! I shouldn't have said it."

"You may say what you please. I am forced in general to be very discreet, but you are both such particular friends of Charles's that I may be allowed to speak my mind - which is that it would be better if the marriage never took place."

"Of course it would be better! There was never anything more unfortunate! We laughed at Charley when it began, but it has turned out to be no laughing matter. It was all the Prince's fault for making the introduction in the first place."

"Nonsense, Gordon! If he had not someone else would have done it. I am afraid Charles is pretty hard hit, Lady Worth."

"I am afraid so, too. I wish he were not, but what can one do?"

"One can't do anything," said Gordon. "That's the sad part of it: to be obliged to watch one of your best friends making a fool of himself."

"Do you dislike Lady Barbara?"

"No. I like her, but the thing is that I like Charley much more, and I can't see him tied to her for the rest of his life."

"It may yet come to nothing."

"That's what I say, but Fitzroy will have it that if Babs throws him over it will be the end of him."

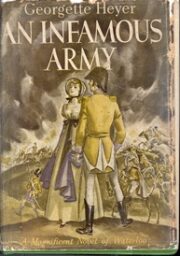

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.