The month wore on; the weather grew warmer; no more friendly logfires in the grates, no more fur-lined pelisses for the ladies. Out came the cambrics and the muslins: lilac, pomona green, and pale puce, made into wispy round dresses figured with rosebuds, with row upon row of frills round the ankles. Knots of jaunty ribbons adorned low corsages, and gauze scarves floated from plump shoulders in a light breeze. The feathered velvet bonnets and the sealskin caps were put up in camphor. Hats were the rage; chip hats, hats of satin straw, of silk, of leghorn, and of willow: high-crowned, flat-crowned, with full-poke fronts, and with curtailed poke fronts: hats trimmed with clusters of flowers, or bunches of bobbing cherries, with puffs of satin ribbons, drapings of thread net, and frills of lace. Winter half boots of orange Jean or sober black kid were discarded: the ladies tripped over cobbled streets in sandals and slippers. Red morocco twinkled under rushed skirts; Villager hats and Angouleme bonnets framed faces old or young, pretty or plain; silk openwork mittens covered rounded arms; frivolous little parasols on long beribboned handles shaded delicate complexions from the sun's glare. Denmark Lotion was in constant demand, and Distilled Water of Pineapples; strawberries were wanted for sunburnt cheeks; Chervil Water, for bathing a freckled skin.

The balls, the concerts, the theatres continued, but picnics were added to the gaieties now, charming expeditions, with flowering muslins squired by hot scarlet uniforms; the ladies in open carriages; the gentlemen riding gallantly beside; hampers of cold chicken and champagne on the boxes; everyone lighthearted; flirtation the order of the day. There were reviews to watch, fetes to attend; day after day slid by in a pursuit of pleasure; days that were not quite real, that belonged to some half-realised dream. Somewhere in the south was a Corsican ogre, who might at any moment break into the dream and shatter it, but distance shrouded him; and, meanwhile, into the Netherlands was streaming an endless procession of British troops, changing the whole face of the country, swarming in every village; lounging outside estaminets, in forage caps, with their jackets unbuttoned; trotting down the rough, dusty roads with plumes flying and accoutrements jingling; haggling with shrewd Flemis farmers in their broken French; making love to giggling girls in starched white caps and huge voluminous skirts: spreading their Flanders tents over the meadows: striding through the streets with clanking spurs and swinging sabretaches. Here might be seen a looped and tasselled infantry shako, narrow-topped and leathernpeaked; there the bell-topped shako of a Light Dragoon, with its short plume and ornamental cord; o: the fur cap of a hussar; or the glitter of sunlight on a Heavy Dragoon's brass helmet, with its jutting crest and waving plume.

Like bright colours in a kaleidoscope, merging into everchanging patterns, the troops were being drafted over the countryside. Life Guardsmen in scarlet and gold, mounted on great black chargers, sleek as satin and splendid with polished trappings, woke dozing villages on the Dender; Liedekerke gaped at the Blues, swaggering up the street as though they owned it: Schendelbeke girls came running to see the hussars ride past with tossing pelisses, and crusted jackets: Castre and Lerbeke billet Light Dragoons in blue with silver lace, and facings of every colour; crimson, yellow, buff, scarlet; Brussels fell in love with Highland kilts and jaunty bonnets, and blinked at trim riflemen in their Jack-a-Dandy green uniforms; Enghien and Grammont swarmed with the Footguards, the Gentlemen's Sons, with their hosts of dashing young ensigns and captains, all so smart and gay, riding in point-to-point races, hurrying off to Brussels in their best clothes to dance the night through, or entertaining bevies of lovely ladies at fetes and picnics. But thundering and clattering along the roads that led from Ostend came the Artillery, grim troops in sombre uniforms and big black helmets, scaring the lighthearted into momentary silence as they passed, for though the Guards danced, and the cavalry made love, and line regiments scattered far and near swarmed over the country like noisy red ants, it was the sight of the guns that made the merrymakers realise how close they stood to war. All through April and the early weeks in May they landed one after another in the Netherlands: Ross, with his Chestnut Troop of 9-pounders; bearded Major Bull, with heavy howitzers; Mercer, with his artist's eye for landscape and his crack troop; Whinyates, with his cherished Rockets; Beane; Gardiner; Webber-Smith; and the beau ideal of every artillery officer, Norman Ramsay, of Fuentes de Onoro fame. After the troops game the field brigades: Sandham's, Bolton's, Lloyd's, Sinclair's, Rogers'; all armed with five gleaming 9 pounders and one howitzer. They were an imposing sight; ominous enough to give a pause to gaiety.

But the merrymaking went on, uneasy under the surface, sometimes a little hectic, as though while the sun continued to shine and the Ogre to remain in his den, the civilians and the soldiers and the lovely ladies were being driven on to cram into every cloudless day all the fun and the gaiety it could hold. The Duke gave ball after ball; there were Court parties at Laeken; reviews at Vilvorde; excursions to Ath, and Enghien, and Ghent; picnics in the cool Forest of Soignes.

There was a rumour of movement on the frontier; a tremor of fear ran through Brussels. Count d'Erlon was marching on Valenciennes with his whole corps; the French were massing on the Allied front, a hundred thousand strong; the Emperor had left Paris: he was at Conde; he was about to launch an attack. It was false: the Emperor was still in Paris, and had postponed his meeting of the Champ de Mai until the end of the month. The ladies and the civilians, poised for flight, could relax again: there was nothing to fear. The Duke had told Mr Creevey that it would never come to blows; and was holding another ball.

"Pooh! Nonsense!" said the Duke. "Nothing to be afraid of yet!"

"I never saw a man so unaffected in my life!" said Mr Creevey. "He is as cheerful as a schoolboy, and talks as though there were no possibility of war!"

"Then he is damned different with you from what he is with me," said Sir Charles Stuart bluntly.

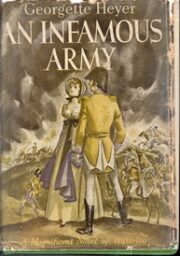

"I have got an infamous Army, very weak, and ill-equipped, and a very inexperienced staff," wrote the Duke, in the midst of his balls, and his reviews, his visits to Ghent, and his latest charming flirtation.

"Pooh! Nonsense," said the Duke, but wrote to Hill at Grammont: "Matters look a little serious on the frontier."

The Duke knew as well as any man what was stirring beyond the frontier, for he had got Colonel Grant out in charge of the Intelligence, and no one knew better than Grant how to obtain desired information. More reliable than the data collected by Clarke and his French spies were Grant's brief reports sent in to General Dornberg at Mons, and forwarded on by him to Brussels. Grant told of bridges and roads being broken up in the Sambre district, as though for defence; of Count d'Erlon's Corps lying between Valenciennes and Maubeuge in four divisions of infantry; of Reille at Avesnes, with five infantry divisions and three cavalry; of Vandamme between Lezieres and Rocroi; and of Count Lobau, at Laon. His information was precise and always to be trusted: no flights into the realms of conjecture for Colonel Grant, a dry Scot, dealing only in facts and figures. Oh Yes! matters certainly looked serious on the frontier; and his lordship had received, besides, disquieting Intelligence of a huge body of cavalry forming. Sixteen thousand heavy cavalry were in readiness to take the field, and all over France horses were being bought, to bring the total up to forty thousand or more. A report -was spread of Murat's having fled by sea from Italy; it was supposed that he would be put in command of this mass of cavalry, for who so brilliant as Murat in cavalry manoeuvres? More serious still was the news that Soult had accepted the office of Major-General under the emperor. That would bring many wavering men over to Napoleon, for Soult's was a name that carried weight.

The Duke of Brunswick arrived, with his Black Brunswickers: men in sable uniforms, with a skull and crossbones on their shakos, and the death of the Duke's father at Jena to avenge. A handsome man, the Duke, gallant in the field and stately in the ballroom, with gentle manners and a grave, sweet smile. His men were quartered at Vilvorde, north of Brussels, but he himself was continually at Headquarters, troubled over the eternal question of subsidies.

The Nassauers were on the way, led by General Kruse, and a hopeful young Prince, whom his lordship had promised to take into his family. Rather an anxiety, these hereditary princelings, but they were all of them agog to fight under his lordship, flatteringly deferential and eager to be of use.

Blucher moved his Headquarters from Liege to Hannut, drawing closer to the Anglo-Allied Army; De Lancey arrived from England with his young bride. taking Sir Hudson Lowe's place. With a deputyquartermaster-general he knew, and could trust to do his work without for ever wishing to copy Prussian methods, his lordship found his path smoother. He still had General Roder with him, but meant to drop a word in Blucher's ear when he next saw him. The fellow would have to be removed: he could not learn to fit into the pattern, or to get over his anti-British prejudice. The other commissioners gave his lordship no trouble: Alava was an old friend; he had a real value for clever Pozzo di Borgo from Russia; liked Baron Vincent from Austria; and was on pretty good terms with Netherlands Count van Reede.

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.