"Oh, you don't frighten us, Etienne!" said Barbara. .When Boney comes - if he comes, which I am beginning to doubt - you will meet him at the frontier, and send him about his business. Or he may send you about yours. I shall certainly remain in Brussels. How exciting to be besieged!"

"How can you talk so?" Judith said, vexed at the flippancy of these remarks. "You do not know what you are saying! Come, it is time we were returning to the chateau!"

But at this Barbara began to take a perverse interest in her surroundings, desiring Lavisse to name all the hamlets she could perceive, and wishing that she could explore the dark belt of woods some miles to the east of them. From where they stood, half a mile to the west of La Belle Alliance, a good view of the undulating country towards Brussels could be obtained, and not until Lavisse had pointed out insignificant farmstead such as La Hay Sainte, north of La Belle Alliance, on the chaussee; and obscure villages such as Papelotte. and Smohain, away to the east, could she be induced to quit the spot. But at last, when she had satisfied herself that the rising ground beyond the hollow crossroad that intersected the chaussee made it impossible for her to see Mont St Jean, and that the wood she wished to explore was quite three miles away, she consented to go back to the Chateau.

Lady Taverner had been dozing by the fire, and woke with a guilty start when the others rejoined her. A glance at the clock on the mantelpiece made her exclaim that she had no notion that the afternoon could be so far advanced. She began to think of her children, of course inconsolable without her, and begged Judith to order the horses to be put to.

This was soon done, and in a very short time Harriet was seated in the barouche, warmly tucked up in a rug, with her hands buried deep in her muff.

Barbara was standing in the doorway when Judith came out of the house, and said: "I wonder where Charles is now?"

"In Ghent, I suppose," Judith replied.

"I wish he had been with us," Barbara said, with a faint sigh.

"I wish it too."

"Oh! you are disliking me again? Well, I am sorry for it, but the truth is that respectable females and I don't deal together. I should be grateful to you for getting this party together. Shall I thank you? Confess that it has been an odious day!"

"Yes, odious," Judith said.

She directed a somewhat chilly look at Barbara as she spoke, and for an instant thought that she saw the glitter of tears on the ends of her lashes. But before she could be sure of it Barbara had turned from her, and was preparing to mount her horse. The next glimpse she had of her face made the very idea of tears seem absurd. She was laughing, exchanging jests with Peregrine, once more in reckless spirits.

Any plan that Peregrine might have formed of deserting the barouche was nipped in the bud by his sister, who said so pointedly that she was glad to have the escort of one gentleman at least that there was nothing for him to do but jog along beside the carriage with the best grace he could muster.

Lavisse and Barbara soon allowed their horses to drop into a walk; the barouche outstripped them, and was presently lost to sight over the brow of a slight hill. Lavisse studied Barbara's profile with a faint smile, and said softly: "Little fool! Little adorable fool!"

"Don't tease me! I could weep with vexation!"

"I know well that you could. But why?"

"Oh, because I'm bored - tired - anything that you please!"

"It does not please me that you should be bored or tired. I do not wonder at it, however. For me, these saintly Englishwomen are the devil."

"I don't dislike Lady Worth, if only she would not look so disapproving."

"Consider, my Bab, she will do so all your life."

"Oh, confound her, I'll take care she don't get the chance!"

"Ma pauvre, I see you surrounded by prim relatives, growing staid - or mad!"

"Wretch! Be quiet!"

"But no, I will not be quiet. Figure to yourself the difference were you to marry me!"

An irrepressible laugh broke from her. "I do. I should then be surrounded by your light-o'-loves. I have seen enough of that in my own family to be cured of wanting to marry a rake."

"You have in England a saying that a reformed rake -"

"My dear Etienne, if you were reformed you would be as dull as the next man. You are wasting your eloquence. I do not love you more than a very little. You are an admirable flirt, I grant, and I find you capital company."

"Do you find your colonel - capital company?"

She turned her head, regarding him with one of her clear looks. "Do you know, I have never thought of that: it has not occurred to me. It is the oddest thing, but if you were to ask me, what does he look like? how does he speak? I couldn't tell you. I think he is handsome; I suppose him to be good company, because it doesn't bore me to be with him. But I can't particularise him. I can't say, he is handsome, he is witty, or he is clever. I can only say, he is Charles."

The smile had quite faded from his face; his horse leapt suddenly under a spur driven cruelly home: "Ah, parbleu, you are serious then!" he exclaimed. "You are lovesick - besotted! I wish you a speedy recovery, ma belle!"

Chapter Ten

Judith saw nothing of Barbara on the following day, but heard of her having gone to a fete at Enghien, given by the Guards. She was present in the evening at a small party at Lady John Somerset's, surrounded by her usual court, and had nothing more than a nod and a wave of the hand to bestow upon Judith. The Comte de Lavisse had returned to his cantonments, but his place seemed to be admirably filled by Prince Pierre d'Aremberg, whose attentions, though possibly not serious, were extremely marked.

If Barbara missed Colonel Audley during the five days of his absence, she gave no sign of it. She seemed to plunge into a whirl of enjoyment; flitted from party to party; put in an appearance at the Opera; left before the end to attend a ball; danced into the small hours; rode out before breakfast with a party of younger officers; was off directly after to go to the races at Grammont; reappeared in Brussels in time to grace her sister-in-law's soiree; and enchanted the company by singing 0 Lady, twine no wreath for me, which had just been sent to her from London, along with a setting of Lord Byron's famous lyric, Farewell, Farewell!

"How can she do it?" marvelled the Lennox girls. "We should be dead with fatigue!"

On April 20th Brussels was fluttered by the arrival of a celebrated personage, none other than Madame Catalani, a cantatrice who had charmed all Europe with her trills and her quavers. Accompanied by her husband, M. de Valbreque, she descended upon Brussels for the purpose of consenting graciously (and for quite extortionate fees) to sing at a few select parties.

On the same evening Wellington drove into Brussels with his suite, and Colonel Audley, instead of ending a long day by drinking tea quietly at home and going to bed, arrayed himself in his dress uniform and went off to put in a tardy appearance at Sir Charles Stuart's evening party. He found his betrothed in an alcove, having each finger kissed by an adoring young Belgian, and waited perfectly patiently for this ceremony to come to an end. But Barbara saw him before her admirer had got beyond the fourth finger, and pulled her hands away, not in any confusion, but merely to hold them out to the Colonel. "Oh, Charles! You have come back!" she cried gladly.

The Belgian, very red in the face, and inwardly qwaking, stayed just enough for Colonel Audley to challenge him to a duel if he wished to, but when he found that the Colonel was really paying no attention to him, he discreetly withdrew, thanking his gods that the English were a phlegmatic race.

The Colonel took both Barbara's hands in his. Mischief gleamed in her eyes. She said: "Would you like to finish Rene's work, dear Charles?"

"No, not at all," he answered, drawing her closer.

She held up her face. "Very well! Oh, but I am glad to see you again!"

They sat down together on a small sofa. "You did not appear to be missing me very much!" said the Colonel.

"Don't be stupid! Tell me what you have been doing!"

"There's nothing to tell. What have you been doing? Or daren't you tell me?"

"That's impertinent. I have been forgetting Charles in a whirl of gaiety."

"Faithless one!"

"I have been to the Races, and was quite out of luck; I went to the Opera, but it was Gluck and detestable; I have danced endless waltzes and cotillions, but no one could dance as well as you; and I went to a macao party, and was dipped; to Enghien, and was kissed -"

"What?"

He had been listening with a smile in his eyes, but this vanished, and he interrupted with enough sharpness in his voice to arrest her attention and make her put up her chin a little.

"Well?"

"Did you mean that?"

"What, that I was kissed at Enghien? My dear Charles!"

"It's no answer to say 'My dear Charles', Bab."

"But can you doubt it? Don't you think I am very kissable?"

"I do, but I prefer that others should not."

"Oh no! how dull that would be!" she said, sparkling with laughter.

"Don't you agree that there is something a trifle vulgar in permitting Tom, Dick, and Harry to kiss you?"

"That's to say I'm vulgar, Charles. Am I, do you think?"

"The wonder is that you are not."

"The wonder?"

"Yes, since you do vulgar things."

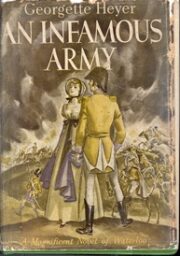

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.