"How ironic!" remarked Worth, who had come back into the room from seeing his other guests off. "Is it true, or just one of your stories, Creevey?"

"No, no, I promise you it's quite true! I knew you would enjoy the joke."

Lady Worth, who had accorded the tale at this second hearing no more than a polite smile, said in a reflective tone: "It is certainly very odd to think of Marmont in particular being in the English camp."

"The Allied camp, my love," corrected the Earl, with a sardonic smile.

"Well, yes," she admitted, "but you know I can't bring myself to believe that the Dutch-Belgian troops count for much, while as for the Prussians, the only one I have laid eyes on is General Roder, and - well -!" She made an expressive gesture. "He is always so stiff, and takes such stupid offence at trifles, that it puts me out of all patience with him."

"Yes, he will never do for the Duke," agreed Mr Creevey. "Hamilton was telling me there is no dealing with him at all. He thinks himself insulted if any of our officers remain seated in his presence. Such stuff! A man who sets so much store by all that ceremonious nonsense won't do for the Duke's Headquarters. They couldn't have made a worse choice of Commissioner. There's another man, too, who they say will never do for the Duke." He nodded, and pronounced: "Our respected Quartermaster-General!"

"Oh, poor Sir Hudson Lowe! He is very stiff also," said Lady Worth. "People say he is an efficient officer, however."

"I daresay he may be, but you know how it is with these fellows who have served with the Prussians: there's no doing anything with them. Well, no doubt we shall see some changes when the Beau arrives from Vienna."

"If only he would arrive! It is very uncomfortable with him so far away. One cannot help feeling uneasy. Now that all communication with Paris has been stopped, war seems so very close. Then Lord Fitzroy Somerset and all the Embassy people being refused passports to come across the frontier, and having to embark from Dieppe! When our Charge d'Affaires is treated like that it is very bad, you must allow."

"Yes," interjected Peregrine, "and the best of our troops being in America! That is what is so shocking! I can't see how any of them can be brought back in time to be of the least use. When I saw the Prince he was in expectation of war breaking out at any moment."

"No chance of that, I assure you. Young Frog don't know what he's talking about. Meanwhile, we have some very fine regiments quartered here, you know."

"We have some very young and inexperienced troops," said Worth. "Happily, the cavalry did not go to america."

"Of course, you were a hussar yourself, but you must know very well there's no sense in cavalry without infantry," replied Peregrine knowledgeably. "Only to think of all the Peninsular veterans shipped off to that curst American war! Nothing was ever so badly contrived."

"It is easy to be wise after the event, my dear Perry."

Lady Worth, who had listened to many such discussions, interposed to give the conversation a turn towards less controversial subjects. She was assisted very readily by Mr Creevey, who had some entertaining scandal to relate, and for the remainder of his visit nothing was talked of but social topics.

Of these there were many, since Brussels overflowed with English visitors. The English had been confined to their own island for so long that upon the Emperor Napoleon's abdication and retirement to Elba they had flocked abroad. The presence of an Army of Occupation in the Low Countries made Brussels a desirable goal. Several provident Mamas conveyed marriageable daughters across the Channel in the wake of the Guards, while pleasure-seeking ladies such as Caroline Lamb and Lady Vidal packed up their most daring gauzes and established their courts in houses hired for an indefinite term in the best part of Brussels.

The presence of the Guards was not, of course, the only attraction offered by Brussels. Mr Creevey, for instance, had brought his good lady to a snug little apartment in the Rue du Musee for her health's sake. Others had come to take part in the festivities attendant upon the long-exiled William of Orange's instatement as King of the Netherlands.

This gentleman, whom Mr Creevey and his friends called the Frog, had been well known in London; and his elder son, the Hereditary Prince of Orange, was a hopeful young man of engaging manners, and a reputation for dashing gallantry in the field, who had lately enjoyed a brief engagement to the Princess Charlotte of Wales. The breaking off of the engagement by that strong-minded damsel, though it had made his Highness appear a trifle ridiculous in English eyes, and afforded huge gratification to Mr Creevey and his friends, did not seem to have cast any sort of cloud over the Prince's spirits. It was felt that gaiety would attend his footsteps; nor were the seekers after pleasure destined to be disappointed. Within its old ramparts, Brussels became the centre of all that was fashionable and light-hearted. King William, a somewhat uninspiring figure was proclaimed with due pomp at Brussels, and if his new subjects, who had been quite content under Bonapartist regime, regarded with misgiving their fusion with their Dutch neighbours, this was not allowed to appear upon the surface. The Hereditary Prince, who spoke English and French better than hisnative tongue, and who announced himself quite incapable of supporting the rigours of life at The Hague, achieved a certain amount of popularity which might have been more lasting had he not let it plainly be seen that although he liked his father's Belgian subjects better than his Dutch ones, he preferred the English to them all. The truth was, he was never seen but in the society of his English friends, a circumstance which had caused so much annoyance to be felt that the one man who was known to have influence over him was petitioned to write exhorting him to morediplomatic behaviour. It was a chill December day when M. Fagel brought his Highness a letter from the English Ambassador in Paris, and there was nothing in the austere contents of the missive to make the day seem warmer. A letter of reproof from his Grace the Duke of Wellington, however politely worded it might be, was never likely to produce in the recipient any other sensation than that of having been plunged into unpleasantly cold water. The Prince, with some bitter animadversions upon tale-bearers in general, and his father in particular, sat down to write a promise to his mentor of exemplary conduct, and proceeded thereafter to fulfil it by entering heart and soul into the social life of Brussels.

But except for a strong Bonapartist faction the Bruxellois also liked the English. Gold flowed from careless English fingers into Belgian pockets; English visitors were making Brussels the gayest town in Europe, and the Bruxellois welcomed them with open arms. They would welcome the Duke of Wellington too when at last he should arrive. He had been received with enormous enthusiasm a year before, when he had visited Belgium on his way to Paris. He was Europe's great man, and the Bruxellois had accorded him an almost hysterical reception, even cheering two very youthful and self-conscious aides-de-camp of his who had occupied his box at the opera one evening. There had been a mistake, of course, but it showed the goodwill of the Bruxellois. The Bonapartists naturally could not be expected to share in these transports, but it was decidedly not the moment for a Bonapartist to proclaim himself, and these gentry had to be content with holding aloof from the many fetes, and pinning their secret faith to the Emperor's star.

The news of Napoleon's landing in the south of France had had a momentarily sobering effect upon the merrymakers, but in spite of rumours and alarms the theatre parties, the concerts, and the balls had still gone on, and only a few prudent souls had left Brussels. There was, however, a general feeling of uneasiness.

Vienna, where the Duke of Wellington was attending Congress, was a long way from Brussels, and whatever the Prince of Orange's personal daring might be it was not felt that two years spent in the Peninsula as one of the Duke's aides-de-camp were enough to qualify a young gentleman not yet twenty-four for the command of an army to be pitted against Napoleon Bonaparte. Indeed, the Prince's first impetuous actions, and the somewhat indiscreet language he held, alarmed serious people not a little. The Prince entertained no doubt of being able to account for Bonaparte; he talked of invading France at the head of the Allied troops; wrote imperative demands to England for more men , more munitions; invited General Kleist to march his Prussians along the Meuse to effect a junction with him and showed himself in general to be so magnificently oblivious of the fact that England was not at war with France, that the embarrassed Government in some haste despatched Lieutenant-General Lord Hill to explain the peculiar delicacy of the situation to him.

The choice of mentor was a happy one. A trifle elated the Prince of Orange was in a brittle mood, ready to resent the least interference in his authority. General Clinton, whom he disliked, and Sir Hudson Lowe , whom he thought a Prussianised martinet, found themselves unable to influence his judgment, and succeeded only in offending. But no one had ever been known to take offence at Daddy Hill. He arrived in Brussels looking more like a country squire than a distinguished general, and took the jealous young commander gently in hand. The anxious breathed again; the Prince of Orange might be in a little huff at the prospect of being soon relieved of his command, but he was no longer refractory, and was soon able to write to Lord Bathurst, in London, announcing the gratifying intelligence that although it would have been mortifying to him to give up his command to anyone else, to the Duke he could do it with pleasure; and could even engage to serve him with as great a zeal as when he had been his aide-de-camp.

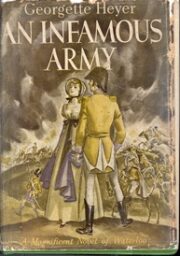

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.