"Devil of a tartar, my grandfather," said Lord Harry. "Used to be a dead shot - daresay he still is, but he don't go about picking quarrels with people these days, of course. Killed his man in three duels before he met my grandmother. Those must have been good times to have lived in! But I believe he settled down more or less when he married. George is the living spit of what he used to be, if you can trust the portraits. Bab and Vidal take after my great-grandmother. She was red-haired, too, and French into the bargain. And her husband - my great-grandfather, that is - was the devil of a fellow!" He tossed off a glass of wine, and added, not without pride: "We're a shocking bad set, you know. All ride to the devil one way or another. As for Bab, she's as bad as any of us."

The Lady Barbara seemed, that evening, to be determined to prove the truth of this assertion. No folly was too extravagant for her to throw herself into; her flirtations shocked the respectable; the language she used gave offence to the pure-tongued; and when she crowned an evening of indiscretions by organising a table of hazard, and becoming, as she herself announced, badly dipped at it, it was felt that she had left nothing undone to set the town by the ears.

She was too busy at her hazard table to notice Colonel Audley's departure, nor did he attempt to interrupt her play to take his leave. But seven o'clock next morning found him cantering down the Allee Verte to meet a solitary horse-woman mounted on a grey hunter.

She saw him approaching, and reined in. When he reached her she was seated motionless in the saddle, awaiting him. He raised two fingers to his cocked hat. "Good morning! Are you in a quarrelsome humour today?" he asked.

She replied abruptly: "I did not expect to see you."

"We don't start for Ghent until noon."

"Ghent?"

"Yes, Ghent," he repeated, not quite understanding her blank stare.

"Oh, the devil! What are you talking about?" she demanded with a touch of petulance. "Are you going to Ghent? I did not know it."

"Didn't you? Then I don't know what the devil I'm talking about," he said.

A laugh flashed in her eyes. "I wish I didn't like you, but I do - I do!" she said. "Do you wonder that I didn't expect to see you here this morning?"

"If it was not because you thought me already on my way to Ghent I most certainly do."

"Odd creature!" She gave him one of her direct looks, and said: "I behaved very shabbily to you last night."

"You did indeed. What had I done? Or were you merely cross?"

"Nothing. Was I cross? I don't know. I think I wanted to show you how damnably I can conduct myself."

"Thank you," said the Colonel, bowing in some amusement. "What will you show me next? How well you can conduct yourself?"

"I never conduct myself well. Don't laugh! I am in earnest. I am odious, do you understand? If you will persist in liking me, I shall make you unhappy."

"I don't like you," said the Colonel. "It was true what I told you the first time I set eyes on you. I love you."

She looked at him with sombre eyes. "How can you do so? If you were in a way to loving me did not that turn to dislike when you saw me at my worst?"

"Not a bit!" he replied. "I will own to a strong inclination to have boxed your ears, but I could not cease to love you, I think, for any imaginable folly on your part." He swung himself out of the saddle, and let the bridle hang over his horse's head. "May I lift you down? There is a seat under the trees where we can have our talk out undisturbed."

She set her hand on his shoulder, but said, half mournfully: "This is the greatest imaginable folly, poor soldier."

"I love you most of all when you are absurd," said the Colonel, lifting her down from the saddle.

He set her on her feet, but held her for an instant longer, his eyes smiling into hers; then his hands squesed her waist, and he gathered up both the horses' bridles, and said: "Let me take you to the secluded nook I have discovered."

"Innocent!" she said mockingly, falling into step side him. "I know all the secluded nooks."

He laughed. "You are shameless."

She looked sideways at him. "A baggage?"

"Yes, a baggage," he agreed, lifting her hand to his lips a moment.

"If you know that, I consider you fairly warned, and shall let you run on your fate as fast as you please."

"Faute de mieux," he remarked. "Here is my nook. Let me beg your ladyship to be seated!"

"Oh, call me Bab! Everyone does." She sat down, and began to strip off her gloves. "Have you still my rose?" she enquired.

He laid his hand upon his heart. "Can you ask?"

"I began to think you an accomplished flirt. I hope the thorns may not prick you."

"To be honest with you," confessed the Colonel, "the gesture was metaphorical."

She burst out laughing. "Your trick! Tell me what it is you want! To flirt with me? I am perfectly willing. To kiss me? You may if you choose."

"To marry you," he said.

"Ah, now you are talking nonsense! Has no one warned you what bad blood there is in my family?"

"Yes, your brother Harry. I am much obliged to him, and to you, and must warn you, in my turn, that I had an uncle once who was so much addicted to the bottle that he died of it. Furthermore, my grandfather -"

She put up her hands. "Stop, stop! Abominable to laugh when I am in earnest! If I married you we should certainly fight."

"Not a doubt of it," he agreed.

"You would wish to make me sober and wellbehaved, and I -"

"Never! To shake you, perhaps, but I am persuaded your sense of justice would pardon that."

"My sense of justice might, but not my temper. I should flirt with other men: you would not like that."

"No, nor permit it."

"My poor Charles! How would you stop me?"

"By flirting with you myself," he replied.

"It would lack spice in a husband. I don't care for marriage. It is curst flat. You do not know that; but I have reason to. Did Gussie tell you I was going to marry Lavisse?"

"Most pointedly. But I think you are not."

"You may be right," she said coolly. "It is more than I can bargain for, though. He is extremely wealthy. I should enjoy the comfort of a large fortune. My debts would ruin you in a year. Have you thought of that?"

"No, but I will, if you like, and devise some means of meeting the difficulty when it arises. Should you object very much to living in a debtors' prison?"

"It might be amusing," she admitted. "But it would come tiresome in time. Things do, you know." She began to play with her riding whip, twisting the lash around her fingers. Watching her, he saw that her eyes had grown dark again, and that she had gripped her lips rather in a mulish fashion. He was content to look at her and presently she glanced up, and said brusquely:

" I'll be plain with you, Charles, you are a fool! Am I your first love?"

"My dear! No!"

"The more shame to you. Don't you know - ? Good God, can you not see that we should never deal together? We are not suited!"

"No, we are not suited, but I think we might deal together," he answered.

"I have been spoilt from my cradle!" she flung at him. "You know nothing of me! You have fallen in love with my face. In fact, you are ridiculous!"

He said rather ruefully: "Do you think I don't know it? I can discover no reason why you should look with anything but amusement upon my suit. I am a younger son, with no prospects beyond the Army -"

"Gussie said that," she interrupted, her lip lifting a little.

"She was right."

She put her whip down; something glowed in her eyes. "Have you nothing to recommend you to me, then?"

"Nothing at all," he replied, with a faint smile.

She leaned towards him; sudden tears sparkled on her lashes; her hands went out to him impulsively. "Nothing at all! Charles, dear fool! Oh, the devil! I'm crying!"

She was in his arms, and raised her face for his kiss. Her hands gripped his shoulders; her mouth was eager, and clung to his for a moment. Then she put her head back, and felt him kiss her wet eyelids.

"Oh, rash," she murmured. "I darken 'em Charles - my eyelashes! Does it come off?"

He said a little unsteadily: "I don't think so. What odds?"

She disengaged herself. "My dear, you are certainly mad! Confound it, I never cry! How dared you look at me just so? Charles, if I have black streaks on my face, I swear I'll never forgive you!"

"But you have not, on my honour!" he assured her. He found his handkerchief, and put his hand under her chin. "Keep still: I will engage to dry them without the least damage being done." He performed this office for her, and held her chin for an instant longer, looking down into her face.

She let him kiss her again, but when he raised his head, flung off his arms, and sprang up. "Of all the absurd situations I ever was in! To be made love to before breakfast! Abominable!"

He too rose, and caught and grasped her hands, holding them in a grip that made her grimace. "Will you marry me?"

"I don't know, I don't know!" Go to Ghent: I won't 'ne swept off my feet!" She gave a gurgle of laughter, and burlesqued herself: "You must give me time to consider, Colonel Audley! Lord, did you ever hear anything so Bath-missish? Let me go: you don't possess :ne, you know."

"Give me an answer!" he said.

"No, and no! Do you think I must marry where I kiss? They don't mean anything, my kisses."

His grip tightened on her hands. "Be quiet! You shall not talk so!"

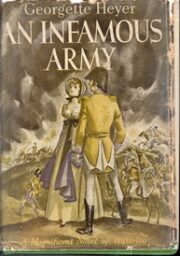

"An Infamous Army" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Infamous Army". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Infamous Army" друзьям в соцсетях.