“It be a cold ’un today, Mr. Darcy, sir.” He shivered despite his coat and muffler.

“Indeed, Harry! Tell James to keep the horses moving, and you may come with me.”

“Thank ’e, sir. James!” Harry went over to the box to give the instructions and hurried back to follow Darcy into the establishment. The bell on the door rang merrily as they entered, bringing Mr. Hatchard’s eyes up from his counter.

“Mr. Darcy, so good to see you, sir!” He advanced upon them. Darcy nodded Harry’s dismissal to the servants’ waiting room before returning the greeting. “And how have you enjoyed the volumes sent to you in Hertfordshire? I trust they arrived satisfactorily?”

“Yes, you are most obliging, Hatchard. Anything more in that line?”

“No, sir, not even a whisper. Wellesley’s in winter quarters in Portugal, you know. Perhaps, between parties and balls, someone may find the time to scribble a few lines. I look for a number of manuscripts to arrive in the spring and will certainly keep you apprised.”

“Very good! I am looking for something for Miss Darcy today. Do you have any suggestions?”

“Miss Darcy! Ah, there is so much, despite what Mr. Walter Scott may think.” Mr. Hatchard led him over to an alcove furnished with a table and chairs. In a few moments a stack of volumes were set before him. Darcy paged through the selections, his nose wrinkling over most, if not giving them a frown, in statement of review. Settling on Miss Porter’s The Scottish Chiefs and Miss Edgeworth’s latest volume of Tales from Fashionable Life, he set them on the counter to be wrapped and sauntered down an aisle to browse.

“Darcy! I say, Darcy, what good fortune!” Darcy looked up from the shelf he was perusing to see “Poodle” Byng coming toward him, his trademark canine companion trotting in his wake.

And now it begins. Darcy cast a beseeching glance toward Heaven.

“Darcy, old man, what was that knot you was wearin’ at Melbourne’s last night? Dashed complicated thing. Had the Beau in a snit for the rest of the evening. Bit off poor Skeffington’s head over his waistcoat, don’t you know.” Poodle’s genial smile transformed into one of unwarranted intimacy as he continued. “S’fellow told me it was called the Roquefort, but I told ’im I didn’t believe it. ‘It ain’t the Roquefort,’ says I. ‘Roquefort’s a cheese, you muttonhead.’ It was Vasingstoke said it; everyone knows he was kicked in the brainbox by his pony when he was first breeched. ‘Roquefort’s a cheese,’ says I, ‘and I’ll lay anybody here a monkey that Darcy’d never wear a cheese round his neck,’ didn’t I, Pompey?” He addressed his dog, who yipped obligingly. In firm conviction, they both turned expectant eyes upon Darcy.

“No, Byng, you are quite right. It is the Roquet. And don’t,” he continued hurriedly, “I beg you, ask me for instructions. It is my valet’s creation. Only he can tie the thing.”

“The Roquet! Aha, just wait till I tell Vasingstoke. ‘Strike ’im out of the game,’ is it? Well, no small wonder Brummell was in such high dudgeon! But a hint only, my good fellow, is all I ask. No wish to compete, mind you; just tweak Brummell’s nose a bit.”

Darcy reached behind him and grabbed a book from the shelf. “Please accept my apologies and assurances that I cannot satisfy your request, Byng. I was paying no attention when Fletcher tied it and cannot begin to hint you upon the proper course. You must excuse me and will understand that I cannot keep my cattle waiting outside any longer in this weather and must take this” — he brought forward the volume — “to Hatchard.” He nodded him a bow, stepped around the dog, who followed his movements with a growl, and walked quickly to the counter.

“Will that be all, Mr. Darcy?” Hatchard’s eyebrows then went up in surprise as Darcy laid his subterfuge atop the other books he had chosen. “The new edition of Practical View! I was not aware you had interests in that area!”

“What? Oh…just wrap it with the rest, if you please, and ring for Harry.”

In seconds Harry was at the counter and accepting the package Hatchard had carefully wrapped. Darcy followed him out the door, unwilling to wait inside until the carriage was brought and risk further importunities from Byng and his canine confidante.

Down the street, near St. James’s, Darcy popped in at Hoby’s to be measured for a new pair of boots. There he was forced to fend off more Roquet admirers. He then directed his driver to Leicester Square and Madame LaCoure’s Silkwares Shoppe. With the modiste’s guidance, he chose three lengths of silk and two of muslin, promising to return with his sister to select the appropriate laces and ribbons. Then, it was on to DeWachter’s in Clerken-well, the jeweler patronized by the Darcys for several generations, where he chose a modest but perfectly matched pearl choker and bracelet and accepted Mr. DeWachter’s congratulations on his “triumph” with as much grace as he could. His last stop was the printing establishment from which Georgiana ordered her music. Sweeping up whatever new offerings there were of composers they both admired, Darcy allowed himself and his final packages to be tucked into the carriage.

“Mr. Darcy, sir?” Harry queried as he arranged the parcels and shook out the carriage robe.

“Yes, Harry?”

“What be this ’ere Roquet, sir?”

Darcy sighed heavily. “Fletcher’s new way of tying a neckcloth. Why do you ask, Harry?”

“Oh, sir, I’ve ’ad two gentlemen offer me a golden boy each if I was to smuggle ’em into yer dressing room to see it.” Harry shook his head. “Beggin’ yer pardon, sir, but the Quality be a strange lot sometimes.”

Darcy closed his eyes. “Truer words were never spoken. Let’s go home, Harry.”

Upon his return from his shopping expedition, Darcy was met by Hinchcliffe with several piles of lately delivered cards and invitations entreating his attendance at a staggering number of routs, breakfasts, pugilistic exhibitions, discreet clubs, political meetings, and theatrical performances. Darcy eyed them with dismay and then threw the lot on his desk.

“Shall I send replies in the usual fashion, sir?” Hinchcliffe leaned over and neatly scooped them onto a silver tray.

“Yes. Regrets to any unknown to you beneath a baronet, sincere regrets to any above, and send the rest in to me. As it is, even should you begin immediately, I fear you will be up most of the night.” Hinchcliffe inclined his head in silent agreement and departed for his office.

At the click of the door, a sudden restlessness seized Darcy, propelling him aimlessly about his library. It lacked an hour or more until supper, and although he had planned to dine alone that evening, a perverse wish for some easy companionship gripped him. After the New Year, when he returned to Town with Georgiana, evenings such as this could be pleasantly occupied with the sharing of books and music with his sister. But even as he contemplated these future pleasures, he discovered, to his chagrin, that the prospect did not entirely answer. A gaping, unnamed discontent whose existence he had never suspected arose before him and now threatened to rob him of his satisfaction and complacency.

His pacing brought him to a bookshelf, and with hopes that the discipline involved in following the course of a battle would restore his thoughts to order, he plucked Fuentes de Oñoro from its place and dropped into a chair by the fire. Stretching out his legs to the hearth, he slid his finger along the pages and opened the book to the place held for him by the embroidery threads. As he bent to read, the words blurred in his vision, cast into incomprehensibility by the glint of the firelight on the knotted strands of silk that lay across his page. Elizabeth! How he had resisted every thought of her! His breath quickened as a flood of memories overpowered his mind: Elizabeth at the door of Netherfield, hesitant but determined; on the stair, tired but faithful in the care of her sister; in the drawing room, with arched brow challenging his character; at the pianoforte, unconscious of the grace she brought to her song; at the ball, Milton’s Eve, sparkling of eye, suffused with Edenic loveliness.

She would have laughed at Brummell’s pompous distress over a mere cravat. She would not, he was certain, have been overawed by Lady Melbourne or fainted at Lady Caroline’s scandalous display. He could almost see her in the next chair, smiling at him with that expression which, he had begun to learn, portended something delightful. His vague discontent sharpened at the thought. Uncertainty, delight, longing — they all had crept into his experience unaware, and alone in his home, he suddenly felt their effects most acutely. His fingers closed around the threads. What had Dy cautioned him? To know his ground, yes, but the other? To be doubly sure of the nature of his interest in Bingley’s affairs. How much of his interest was directed solely toward Bingley’s good? Was it nearer to the truth that separating Charles from Miss Jane Bennet was his surest defense against the confliction raised by his own heedless attraction to her sister?

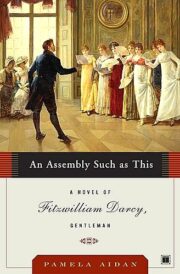

"An Assembly Such as This" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "An Assembly Such as This". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "An Assembly Such as This" друзьям в соцсетях.