"I didn't do those things, Mother Tate," I said quietly. "I tried to discourage our relationship. I even told him the truth about us," I said.

"Yes, you did and viciously drove a wedge between him and me. He knew that I wasn't his real mother. Don't you think that changed things?"

"I didn't want to tell him. It wasn't my place to tell him," I cried, recalling Grandmère Catherine's warnings about causing any sort of split between a Cajun mother and her child. "But you can't build a house of love on a foundation of lies. You and your husband should have been the ones to tell him the truth."

She winced. "What truth? I was his mother until you came along. He loved me," she whined. "That was all the truth we needed . . . love."

A pall fell among us for a moment. Gladys sucked in her anger and closed her eyes.

Beau decided to proceed. "Your son, realizing the love between Ruby and myself, agreed to help us be together. When Gisselle became seriously ill, he volunteered to take her in and pretend she was Ruby so that Ruby could become Gisselle and we could be man and wife."

She opened her eyes and laughed in a way that chilled my blood. "I know all that, but I also know he had little choice. She probably threatened to tell the world he wasn't my son," she said, her flinty eyes aimed at me.

"I would never. . ."

"You'd say anything now, so don't try," she advised.

"Madame," Beau said, stepping forward. "What's done is done. Paul did help. He intended for us to live with our daughter and be happy. What you're doing now is defeating what Paul himself tried to accomplish."

She stared up at Beau for a moment, and as she did so, the gossamer strands of sanity seemed to shred before they snapped behind her eyes. "My poor granddaughter has no parents now. Her mother was buried and her father will be interred beside her."

"Madame Tate, why force us to go to court over this and put everyone through the misery again? Surely you want peace and quiet at this point, and your family—"

She turned her dark, blistering eyes toward Paul's portrait, and those eyes softened. "I'm doing this for my son," she said, gazing up at him with more than a mother's love. "Look how he smiles, how beautiful he is and how happy he is. Pearl will grow up here, under that portrait. At least he'll have that. You," she said, pointing her long, thin finger at me again, "took everything else from him, even his life."

Beau looked at me desperately and then turned back to her. "Madame Tate," he said, "if it's a matter of the inheritance, we're prepared to sign any document."

"What?" She sprang up. "You think this is all a matter of money? Money? My son is dead." She pulled up her shoulders and pursed her lips. "This discussion is over. I want you out" of my house and out of our lives."

"You won't succeed with this. A judge—"

"I have lawyers. Talk to them." She smiled at me so coldly, it made my blood curdle. "You put on your sister's face and body and you crawled into her heart. Now live there," she cursed, and left the room.

Right down to my feet, I ached, and my heart became a hollow ball shooting pains through my chest. "Beau!"

"Let's go," he said, shaking his head. "She's gone mad. The judge will realize that. Come on, Ruby." He reached for me. I felt like I floated to my feet.

Just before we left the room, I gazed back at Paul's portrait. His expression of satisfaction put a darkness in my heart that a thousand days of sunshine couldn't nudge away.

After the funeral drive back to New Orleans, I collapsed with emotional exhaustion and slept into the late morning. Beau woke me to tell me Monsieur Polk had just called.

"And?" I sat up quickly, my heart pounding.

"I'm afraid it's not good news. The experts tell him everything is identical with identical twins, blood type, even organ size. The doctor who treated Gisselle doesn't think anything would show in an X-ray. We can't rely on the medical data to clearly establish identities.

"As far as my being the father of Pearl . . . a blood group test will only confirm that I couldn't be, not that I could. As Monsieur Polk said, those sorts of tests aren't perfected yet."

"What will we do?" I moaned.

"He has already petitioned for a hearing and we have a court date," Beau said. "We'll tell our story, use the handwriting samples. He wants to also make use of your art talent. Monsieur Polk has documents prepared for us to sign so that we willingly surrender any claim to Paul's estate, thus eliminating a motive. Maybe it will be enough."

"Beau, what if it isn't?"

"Let's not think of the worst," he urged.

The worst was the waiting. Beau tried to occupy himself with work, but I could do nothing but sleep and wander from room to room, sometimes spending hours just sitting in Pearl's nursery, staring at her stuffed animals and dolls. Not more than forty-eight hours after Monsieur Polk had filed our petition with the court, we began to get phone calls from newspaper reporters. None would reveal his or her sources, but it seemed obvious to both Beau and me that Gladys Tate's thirst for vengeance was insatiable and she had deliberately had the story leaked to the press. It made headlines.

TWIN CLAIMS SISTER BURIED IN HER GRAVE! CUSTODY BATTLE LOOMS.

Aubrey was given instructions to say we were unavailable to anyone who called. We would see no visitors, answer no questions. Until the court hearing, I was a virtual prisoner in my own home.

On that day, my legs trembling, I clung to Beau's arm as we descended the stairway to get into our car and drive to the Terrebone Parish courthouse. It was one of those mostly cloudy days when the sun plays peekaboo, teasing us with a few bright rays and then sliding behind a wall of clouds to leave the world dark and dreary. It reflected my mood swings, which went from hopeful and optimistic to depressed and pessimistic.

Monsieur Polk was already at the courthouse, waiting, when we arrived. The story had stirred the curious in the bayou as well as in New Orleans. I gazed quickly at the crowd of observers and saw some of Grandmère Catherine's friends. I smiled at them, but they were confused and unsure and afraid to smile back. I felt like a stranger. How would I ever explain to them why I had switched identities with Gisselle? How would they ever understand?

We took our seats first, and then, with obvious fanfare, milking the situation as much as she could, Gladys Tate entered. She still wore her clothes of mourning. She hung on Octavious's arm, stepping with great difficulty to show the world we had dragged her into this horrible hearing at a most unfortunate time. She wore no makeup, so she looked pale and sick, the weaker of the two of us in the judge's eyes. Octavious kept his gaze down, his head bowed, and didn't look our way once.

Toby and Jeanne and her husband, James, walked behind Gladys and Octavious Tate, scowling at us. Their attorneys, William Rogers and Martin Bell, led them to their seats. They looked formidable with their heavy briefcases and dark suits. The judge entered and every-one took his seat.

The judge's name was Hilliard Barrow, and Monsieur Polk had found out that he had a reputation for being caustic, impatient, and firm. He was a tall, lean man with hard facial features: deep-set dark eyes, thick eyebrows, a long, bony nose, and a thin mouth that looked like a slash when he pressed his lips together. He had gray and dark brown hair with a deeply receding hairline so that the top of his skull shone under the courtroom lights. Two long hands with bony fingers jutted out from the sleeves of his black judicial robe.

"Normally," he began, "this courtroom is relatively empty during such proceedings. I want to warn those observing that I won't tolerate any talking, any sounds displaying approval or disapproval. A child's welfare is at stake here, and not the selling of newspapers and gossip magazines to the society people in New Orleans." He paused to scour the crowd to see if there was even the hint of insubordination in anyone's eyes. My heart sunk. He seemed a man void of any emotion, except prejudices against rich New Orleans people.

The clerk read our petition and then Judge Barrow turned his sharp, hard gaze on Monsieur Polk.

"You have a case to make," he said.

"Yes, Your Honor. I would like to begin by calling Monsieur Beau Andreas to the stand."

The judge nodded, and Beau squeezed my hand and stood up. Everyone's eyes were fixed on him as he strutted confidently to the witness seat. He was sworn in and sat quickly.

"Monsieur Andreas, as a preamble to our presentation, would you tell the court in your own words why, how, and when you and Ruby Tate effected the switching of identities between Ruby and Gisselle Andreas, who was your wife at the time."

"Objection, Your Honor," Monsieur Williams said. "Whether or not this woman is Ruby Tate is something for the court to decide."

The judge grimaced. "Monsieur Williams. There isn't a jury to impress. I think I'm capable of understanding the question at hand without being influenced by innuendo. Please, sir. Let's make this as fast as possible."

"Yes, Your Honor," Monsieur Williams said, and sat down.

My eyes widened. Perhaps we would get a fair shake after all, I thought.

Beau began our story. Not a sound was heard through his relating of it. No one so much as coughed or cleared his throat, and when he was finished, an even deeper hush came over the crowd. It was as if everyone had been stunned. Now, when I turned and looked around, I saw all eyes were on me. Beau had done such a good job of telling our story, many were beginning to wonder if it couldn't be so. I felt my hopes rise to the surface of my troubled thoughts.

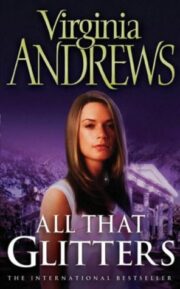

"All That Glitters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All That Glitters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All That Glitters" друзьям в соцсетях.