"What about the child?" Beau threw out in desperation. "She knows her mother."

"She's an infant. I wouldn't think of putting her on a witness stand in a courtroom. She would be terrified, I'm sure."

"No, we can't do that, Beau," I said. "Never." Monsieur Polk sat back. "Let me look into the hospital records, talk to some doctors. I’ll get back to you."

"How long will this take?"

"It can't be done overnight, madame," he said frankly.

"But my baby . . . Oh, Beau."

"Did you consider going to see Madame Tate and talking it out with her? Perhaps this was an impulsive angry act and now she's had some time to reconsider," Monsieur Polk suggested. "It would simplify the problem."

"I don't say this is her motive," he added, leaning forward, "but you might offer to sign over any oil rights, et cetera."

"Yes," I said, hope springing in my heart.

Beau nodded. "It could be driving her mad that Ruby would inherit Cypress Woods and all the oil on the land," Beau agreed. "Let's drive out there and see if she will speak with us. But in the meantime . . ."

"I'll go forward with my research in the matter," Monsieur Polk said. He stood up and put his cigar in the ashtray before leaning over to shake Beau's hand. "You know," he said softly, "what a field day our gossip columnists in the newspapers will have with this?"

"We know." Beau looked at me. "We're prepared for all that as long as we get Pearl back."

"Very well. Good luck with Madame Tate," Monsieur Polk said, and we left.

"I feel so weak, Beau, so weak and afraid," I said as we left the building for our car.

"You can't present yourself to that woman while you're in this state of mind, Ruby. Let's stop for something to eat to build your strength. Let's be optimistic and strong. Lean on me whenever you have to," he said, his face dark, his eyes down. "This is really all my fault," he murmured. "It was my idea, my doing."

"You can't blame yourself solely, Beau. I knew what I was doing and I wanted to do it. I should have known better than to think we could splash water in the face of Destiny."

He hugged me to him and we got into our car and started for the bayou. As we rode, I rehearsed the things I would say. I had no appetite when we stopped to eat, but Beau insisted I put something in my stomach.

The late afternoon grew darker and darker as the sun took a fugitive position behind some long, feather-brushed storm clouds. All the blue sky seemed to fall behind us as we drove on toward the bayou and the confrontation that awaited. As familiar places and sights began to appear, my apprehension grew. I took deep breaths and hoped that I would be able to talk without bursting into tears.

I directed Beau to the Tate residence. It was one of the larger homes in the Houma area, a two-and-a-half-story Greek Revival with six fluted Ionic columns set on pilastered bases a little out from the edge of the gallery. It had fourteen rooms and a large drawing room. Gladys Tate was proud of the decor in her home and her art, and until Paul had built the mansion for me, she had the finest house in our area.

By the time we drove up, the sky had turned ashen and the air was so thick with humidity, I thought I could see droplets forming before my eyes. The bayou was still, almost as still as it could be in the eye of a storm. Leaves hung limply on the branches of trees, and even the birds were depressed and settled in some shadowy corners.

The windows were bleak with their curtains drawn closed or their shades down. The glass reflected the oppressive darkness that loomed over the swamps. Nothing stirred. It was a house draped in mourning, its inhabitants well cloistered in their private misery. My heart felt so heavy; my fingers trembled as I opened the car door. Beau reached over to squeeze my arm with reassurance.

"Let's be calm," he advised. I nodded and tried to swallow, but a lump stuck in my throat like swamp mud on a shoe. We walked up the stairs and Beau dropped the brass knocker against the plate. The hollow thump seemed to be directed into my chest rather than into the house. A few moments later, the door was thrust open with such an angry force, it was as if a wind had blown it. Toby stood before us. She was dressed in black and had her hair pinned back severely. Her face was wan and pale.

"What do you want?" she demanded.

"We've come to speak with your mother and father," Beau said.

"They're not exactly in the mood to talk to you," she spit back at us. "In the midst of our mourning, you two had to make problems."

"There are some terrible misunderstandings we must try to fix," Beau insisted, and then added, "for the sake of the baby more than anyone."

Toby gazed at me. Something in my face confused her and she relaxed her shoulders.

"How's Pearl?" I asked quickly.

"Fine. She's doing just fine. She's with Jeanne," she added.

"She's not here?"

"No, but she will be here," she said firmly.

"Please," Beau pleaded. "We must have a few minutes with your parents."

Toby considered a moment and then stepped back. "I'll go see if they want to talk to you. Wait in the study," she ordered, and marched down the hallway to the stairs.

Beau and I entered the study. There was only a single lamp lit in a corner, and with the dismal sky, the room reeked of gloom. I snapped on a Tiffany lamp beside the settee and sat quickly, for fear my legs would give out from under me.

"Let me begin our conversation with Madame Tate," Beau advised. He stood to the side, his hands behind his back, and we both waited and listened, our eyes glued to the entrance. Nothing happened for so long, I let my eyes wander and my gaze stopped dead on the portrait above the mantel. It was a portrait I had done of Paul some time ago. Gladys Tate had hung it in place of the portrait of herself and Octavious. I had done too good a job, I thought. Paul looked so lifelike, his blue eyes animated, that soft smile captured around his mouth. Now he looked like he was smiling with impish satisfaction, defiant, vengeful. I couldn't look at the picture without my heart pounding.

We heard footsteps and a moment later Toby appeared alone. My hope sunk. Gladys wasn't going to give us an audience.

"Mother will be down," she said, "but my father is not able to see anyone at the moment. You might as well sit," she told Beau. "It will be a while. She's not exactly prepared for visitors right now," she added bitterly. Beau took a seat beside me obediently. Toby stared at us a moment.

"Why were you so obstinate? If there was ever a time my mother needed the baby around her, it was now. How cruel of you two to make it difficult and force us to go to a judge." She glared at me and then turned directly to Beau. "I might have expected something like this from her, but I thought you were more compassionate, more mature."

"Toby," I said. "I'm not who you think I am."

She smirked. "I know exactly who you are. Don't you think we have people like you here, selfish, vain people who couldn't care less about anyone else?"

"But . . ."

Beau put his hand on my arm. I looked at him and saw him plead for silence with his eyes. I swallowed back my words and closed my eyes. Toby turned and left us.

"She'll understand afterward," Beau said softly. A good ten minutes later, we heard Gladys Tate's heels clicking down the stairway, each click like a gunshot aimed at my heart. Our eyes fixed with anticipation on the doorway until she appeared. She loomed before us, taller, darker in her black mourning dress, her hair pinned back as severely as Toby's. Her lips were pale, her cheeks pallid, but her eyes were bright and feverish.

"What do you want?" she demanded, shooting me a stabbing glance.

Beau rose. "Madame Tate, we've come to try to reason with you, to get you to understand why we did what we did," he said.

"Humph," she retorted. "Understand?" She smiled coldly with ridicule. "It's simple to understand. You're the type who care only about themselves, and if you inflict terrible pain and suffering on someone in your pursuit of happiness, so what?" She whipped her eyes to me and flared them with hate before she turned to sit in the high-back chair like a queen, her hands clasped on her lap, her neck and shoulders stiff.

"Much of this is my fault, not Ruby's," Beau continued. "You see," he said, turning to me, "a few years ago we . . . I made Ruby pregnant with Pearl, but I was cowardly and permitted my parents to send me to Europe. Ruby's stepmother tried to have the baby aborted in a run-down clinic so it would all be kept secret, but Ruby ran off and returned to the bayou."

"How I wish she hadn't," Gladys Tate spit, her hating eyes trying to wish me into extinction.

"Yes, but she did," Beau continued, undaunted by her venom. "For better or for worse, your son offered to make a home for Ruby and Pearl."

"It was for worse. Look at where he is now," she said. Ice water trickled down my spine.

"As you know," Beau said softly, patiently, "theirs was not a true marriage. Time passed. I grew up and realized my errors, but it was too late. In the interim, I renewed my relationship with Ruby's twin sister, who I thought had matured, too. I was mistaken about that, but that's another story."

Gladys smirked.

"Your son knew how much Ruby and I still eared for each other, and he knew Pearl was our child, my child. He was a good man and he wanted Ruby to be happy."

"And she took advantage of that goodness," Gladys accused, stabbing the air between us with her long forefinger.

"No, Mother Tate, I—"

"Don't sit there and try to deny what you did to my son." Her lips trembled. "My son," she moaned. "Once, I was the apple of his eye. The sun rose and fell on my happiness, not yours. Even when you were enchanting him here in the bayou, he would love to sit and talk with me, love to be with me. We had a remarkable relationship and a remarkable love between us," she said. "But you were relentless and you charmed him away from me," she charged, and I realized there was no hate such as that born out of love betrayed. This was why her brain was screaming out for revenge.

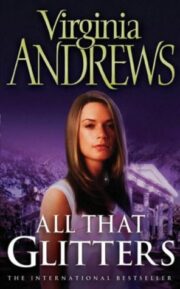

"All That Glitters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All That Glitters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All That Glitters" друзьям в соцсетях.