"I don't know, Beau," I moaned. I was ready to throw up my hands and reveal our elaborate deception.

"We have no other choice now but to see this thing through. Be strong," Beau said firmly. Then he straightened up and smiled at the sight of Jeanne and Pearl approaching.

"She's been calling for her mother. It's so sad, I can't stand it," Jeanne moaned.

"Let me take her," I said.

"You know," Jeanne said as she handed Pearl back to me, "I think she believes you're Ruby. I can't imagine why or how a child would make such a mistake."

Beau and I gazed at each other a moment and then Beau smiled.

"She's just in a state of confusion because of the rapid turn of events, the traveling, the new home," Beau said.

"That's why I was going to suggest you leave her with me. I know what a burden a baby is, but—"

"Oh no," I said sharply. "She's no burden. We have already hired a nanny to help."

"Really?" She grimaced. "Toby said you would."

"Well, why shouldn't we?" Beau said quickly.

"Oh, I didn't mean you shouldn't. I probably would, too, if I . . ."

"Everything's set. We can eat out on the patio, if that's all right with you," Toby said, coming up behind Jeanne.

"Fine," Beau said. "Gisselle?" He looked at me and I sighed. The tension and the emotional weight of seeing Paul this way were the real reason, but Paul's sisters thought I was just being my petulant self as Gisselle. They glanced at each other and tried to hide a smirk.

"It's all right," I said with great effort. "Not that I'm that hungry. Long rides always ruin my appetite," I complained. Ironically, it was a relief to fall back into Gisselle's personality. At least I didn't have the burden of conscience on my heart.

For the first time it occurred to me that this was why Gisselle had been the way she was; and for the moment, at least, I understood and even envied her for being so self-centered. She never felt sorrow over someone else's pain. To Gisselle, the world had been a great playground, a land of magic and pleasure, and anything that threatened that world was either ignored or avoided. Maybe she wasn't so stupid after all.

Except I remembered something Grandmère Catherine once said. "The loneliest people of all are those who were so selfish, they had no one with them in the autumn of their lives."

I wondered if Gisselle, falling down that dark tunnel of unconsciousness, drifting away, realized that now, if she realized anything anymore.

After lunch we let Pearl take a nap. Beau and I sat outside with Paul's sisters drinking café au lait and listening to them complain about Paul's behavior and how their mother was so beside herself because of it, she wasn't seeing anyone or leaving the house.

"Has she been to the hospital to see Ruby?" I asked, very curious.

"Mother hates hospitals," Toby said. "She had Paul at home because she hated being around sick people, and it was a difficult birth. Daddy had to plead with her into going there for our births."

Beau and I exchanged knowing glances, understanding this was part of the fabrication Paul's parents had created to cover up Paul's real mother's identity.

"Are you two going to the hospital to see Ruby?" Jeanne asked.

I thought how Gisselle would respond to such a question first and then replied, "What for? She's always sleeping, isn't she?"

Toby and Jeanne glanced at each other.

"She's still your sister . . . dying," Jeanne said, and then burst into tears. "I'm sorry. I can't help it. I really loved Ruby."

Toby threw her arms around her, rocking and comforting her and shooting glances of reproach my way.

"Maybe we should go to the hospital, Beau," I said quickly, and rose from my chair. I couldn't sit out there with them any longer and pretend to be insensitive, nor could I stand their sorrow over what they thought was my demise.

Beau followed me into the house. He caught up with me in the study, where I, too, had burst into tears that fell scalding on my cheeks.

"Oh, Beau, we shouldn't have come here. I can't stand all this sorrow. I feel it's my fault."

"That's ridiculous. How can it be your fault? You didn't cause Gisselle to get sick, did you? Well . . . did you?"

I ground my eyes dry and took a deep breath. "Paul reminded me of the time I once went with Nina Jackson to see a Voodoo Mama, who put a spell on Gisselle. Maybe that spell never stopped."

"Now, Ruby, you don't seriously believe—"

"I do, Beau. I always have believed in the spiritual powers some people have. My Grandmère Catherine had them. I saw her heal people, comfort them, give them hope, with merely a laying on of her hands."

Beau grimaced skeptically. "So what do you want to do? Do you want to go to the hospital?"

"Yes, I have to go."

"All right, we'll go. Do you want to wait for Pearl to wake up or—"

"No. We'll ask Jeanne and Toby to look after her until we return."

"Fine," Beau said.

"I'll be right down. I've got to get something," I said, and started out.

"What?"

"Something," I said firmly. I hurried upstairs to what had been my suite and slipped in without anyone seeing or hearing me. I went to the dresser and opened the bottom drawer where I had the pouch of five-finger grass Nina Jackson had once given me to ward off evil and the dime with the string through it to wear around my ankle for good luck.

Then I went to the adjoining door and opened it slightly to peek in on Paul. He was fast asleep in his bed, hugging his pillow to him. Over his headboard, hanging like a religious icon, was my picture in a silver frame. The pathetic sight brought hot tears to my eyes again and made my chest ache with the weight of such sadness, I couldn't breathe. I felt as if I had thrown myself into the pot and it was up to me to keep from being boiled.

I dosed the door softly and left the suite. Beau was waiting at the foot of the stairs.

"I've already spoken to Jeanne and Toby," he said. "They'll look in on Pearl until we return."

"Good," I said. Beau didn't ask what I had gone upstairs to get. We drove to the hospital and inquired at the nurses' station for directions to Gisselle's private room. The nurse Paul had hired was sitting in a chair near the bed crocheting. She looked up with surprise, her mouth agape.

"Mr. Tate told me his wife had a twin sister, but I've never seen so identical a set of twins," she said, regaining her composure.

"We're not so identical," I said sternly. Gisselle would have said something like that and would have made her feel uncomfortable. The nurse was happy to excuse herself while we visited. I wanted her out of the room anyway.

As soon as she left, I went to Gisselle's bedside. She had the oxygen tubes in her nose and the IV bag connected to her arm. Her eyes were closed and she looked even smaller and paler than when I had last seen her. Even her hair had grown dull. Her skin had the pallor of the underbelly of dead fish. Beau stood back as I held Gisselle's hand and stared down at her. I don't know what I expected, but there was no sign that she had any awareness whatsoever. Finally, after a sigh. I took out the pouch of five-finger grass and put it under her pillow.

"What's that?" Beau asked.

"Something Nina Jackson once gave me. Inside the bag is a plant with a leaf that is divided into five segments. It brings restful sleep and wards off any evil that five fingers can bring."

"What? You're not serious."

"Each segment has a significance: luck, money, wisdom, power, and love."

"You really believe in this stuff?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. Then I lifted the cover and quickly tied my good-luck dime around Gisselle's ankle.

"What are you doing?"

"This, too, brings good luck and wards off evil," I told him.

"Ruby, what do you think they'll say when they find this stuff?"

"They'll probably think one of my Grandmère's friends came around and did it," I said.

"I hope so. Gisselle would certainly never bring anything like this. She made fun of these things," he reminded me.

"Still, I had to do it, Beau."

"All right. Let's not stay too long, Ruby," he said nervously. "We should return to New Orleans before it gets too late."

I held Gisselle's hand for a moment, said a silent prayer, and touched her forehead. I thought her eyelids fluttered, but maybe that was my hope or my imagination.

"Good-bye, Gisselle. I'm sorry we were never real sisters." I felt a tear on my cheek and touched it with the tip of my right forefinger. Then I brought it to her cheek and touched her with the wetness. Maybe now, maybe finally now, she's crying inside for me, too, I thought, and turned quickly to run out of the room and rush away from the sight of my dying sister.

Paul had still not risen when we returned, but Pearl was up and playing with Jeanne and Toby in the study. Her eyes brightened with happiness when she saw it was me. I wanted to rush to her and hold her dearly in my arms, but Gisselle wouldn't have done that, I told myself, and I kept a check on my emotions.

"We've got to get back to New Orleans," I said abruptly.

"What was it like at the hospital?" Toby asked. "Like talking to yourself," I said. Ironically, that was the truth.

The two sisters nodded with identically melancholy faces.

"You can leave the baby with me," Jeanne suggested. "I don't mind."

"Oh no. We couldn't do that," I said. "I promised my sister I would look after her."

"You? Promised Ruby?"

"At a weak moment," I said, "but I have to keep the promise."

"Why? You're not crazy about children, are you?" Toby asked disdainfully.

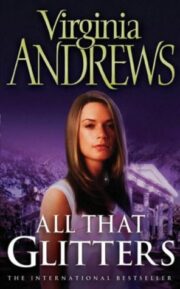

"All That Glitters" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All That Glitters". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All That Glitters" друзьям в соцсетях.