It’s not their fault their son is a jerk.

Levi stopped coming to church not long after he started college. I should feel guilty over how glad that made me, but I don’t. Church always feels a little bit like I’m putting on a show, but with him here it was ten times worse. If I looked at him too much, of course I was still madly in love with him. But if I didn’t look at him at all, I was madly in love (and heartbroken). It was like living under a microscope.

Breakups are a careful and exhausting dance.

That’s exactly what I need. Dance. It clears my mind better than anything else. I stand by the raised little nook that houses the piano and wait for Mrs. Dunlap to finish the postlude. She must feel me there, because she looks away from her sheet music and gives me an overdramatic smile. She presses the keys with a bit more flourish for my benefit, and I lean against the wall humming beneath my breath.

She holds on to the last chords for a long moment, and they ring out in chorus with the organ before the song ends and only the chattering conversations across the hall are left.

“Let me guess.” Mrs. D turns on her bench to look at me. “You want the studio?”

“How’d you know?”

She snorts. “Because it’s all you want. Always has been.”

I know that. And she knows it. Dad still insists I’ll want other things if I give them a try. After living in a house for eighteen years with me, you’d think he would know me better than the lady who teaches my dance class a few times a week.

“You have a key,” Mrs. Dunlap says. “No reason to drag yourself all the way up here to see little old me.”

She gave me a key when I started teaching classes to the younger kids, but I still felt bad about using it without her permission.

“You’re not old.”

She is. The woman is nearly seventy, but she doesn’t look it. She’s lithe and slender, and if she’d dye her gray hair, she could probably pass for fifty, if not younger.

“Oh pish. You don’t need to suck up to me, child.”

I step up on the platform and place a quick kiss on her cheek. “Learn to take a compliment, Mrs. D.”

I turn to go, and she calls out, “Says the girl who never thinks anything is good enough.”

I blow her a kiss and call back my thanks instead of saying the thought that pops into my head.

Good is never good enough.

One of Dad’s mottos. He would frequently tack on, “Good may win games, but great wins titles.”

As I walk back toward him, he manages to peel himself away from the leeches, I mean, parents surrounding him.

He joins me in the aisle, and we head for the door together.

“Lunch?” he grunts.

I shake my head. “Mrs. Dunlap is going to let me use the studio for a while. I’ll just grab something fast after.”

“Sure?”

I nod. “Yep.”

“Okay.”

“Okay.”

We don’t say another word until we’re outside, and I press the button to unlock my car.

“Drive safe,” he says, and then climbs into his own truck.

I turn the key in the ignition and mutter, “Good talking to you, Dad.”

It takes me ten minutes to get to the studio, a nondescript storefront in a strip mall. Not exactly the height of culture, but it’s about all this town has to offer. And it’s been good to me. I’m careful to lock the door behind me and keep the lights off in the front so no one thinks we’re open. I choose the larger of the two studios and push open the door.

Breathing deep, I take in that indescribable smell of the studio. Sweat. Feet. Rosin wood from the barre. You’d think the smell would be unpleasant, but it’s not. It’s home.

Dance had started as a babysitting service while Dad had practice. He enrolled me in everything from piano lessons to Little League softball, so that I was occupied while he did his thing. I’m willing to bet he regrets that first dance class he dumped me in all those years ago.

I switch on the light and drop my bag by the door. Slipping off my street shoes, I dig out my lyrical sandals, which Mrs. Dunlap always calls dance paws. They leave my toes free and wrap just under the pad of my foot, giving me a better surface to spin and slide, but still allowing me the flexibility of being almost barefoot.

I pad over to the stereo system, the floor cold against my toes. I press play on the CD that’s already in there, and start skipping through the songs, waiting for something to speak to me. I flip past a few hip-hop and pop songs, followed by classical music (only in Mrs. D’s dance class would she have Mozart following up “Lady Marmalade”).

I flip through about a dozen songs, each time more and more frustrated with a feeling I can’t quite name. It’s not that I’m angry, though it’s close. Sad doesn’t quite fit either, even though I can feel hints of that dripping from the edges of whatever it is that’s eating at me.

Finally, a song makes me pause. Slow and simple, it starts with a long, low chord and a soft, frenetic beat building beneath. It reminds me of my morning spent at church. Serene on the outside, roiling in the depths.

A voice, smooth and sweet, rings out.

I’m wasted, losing time. I’m a foolish, fragile spine.

Yeah. That sounded like it had enough self-loathing in it to do the trick.

I start the song over and make my way to the center of the floor.

I let the music move me slowly at first, gentle swaying. Then right before the words begin, I burst into movement. I don’t bother dancing a routine I already know. There’s no challenge in that. It’s a battle already won, a feeling already mapped and conquered. No . . . that’s not how I like to dance, not like my father plays football with a book of mastered plays, each carefully designed with no room for mistakes. I dance the way musicians play jazz, with improvisation and soul.

It means I always dance alone. Group and coupled dances don’t exactly leave much room to play and change as you go along. I’m fine with that, though. I’ve gotten quite used to being alone. I thrive that way.

I move how the song tells me, cobbling together a series of steps on the fly. Some of them are familiar, stolen from previous routines, while some leap into existence of their own accord, rustling through my body before my mind even bothers to make sense of what my body is doing.

I make mistakes. I build to a move that doesn’t match with the song. Sometimes I stand there for a few seconds, not sure what to do next, but miraculously . . . it works with the hesitation of the song, of the lyrics. Because sometimes in life, you just have to stand there and do nothing. Overwhelmed by all the versions of ourselves that exist in our minds—who we want to be, who we should be, who we’re not, and who we are—it’s a jungle that can ensnare your feet and confuse your eyes. But sometimes if you stand still, all those things will snap back into place like a rubber band. And if you can get past the sting, you can keep moving, not quite whole, but held together for the moment.

That’s what the dance becomes for me. All the versions of myself. I move toward one corner, playing the perfect daughter, dancing with all the moments I’ve spent in bleachers burning behind my eyelids. Then I drag myself back to center. I take off toward the opposite corner. I throw myself into the highest leap I can manage, drawing on all the most complex combinations I know. That’s the me that doesn’t hesitate or question. That’s the me that dreams. But then mournfully, I pull myself back to center. I keep dancing—the me that placates Stella in order to keep her while simultaneously burning with jealousy, the me that strives to be better than everyone else at dance and school and everything within my control, the me without a mom, that’s too afraid to be feminine or emotional, too afraid I won’t know how or worse that I will and the emotion will consume me, the me that jumped off a balcony and kissed a boy I barely knew just so he’d call me a daredevil and I could pretend for a moment that he spoke the truth. I cover every inch of the studio, and when I drag myself back to the center of the room for the final time, it’s on my hands and knees, slicked with sweat, my version of tears.

I lie flat on my back as the stereo plays “Meet Virginia.” It’s one of Mrs. D’s favorites to use in warm-ups, and it’s already well into the middle of the song.

Pulls her hair back as she screams,

“I don’t really wanna live this life.”

I didn’t notice as I danced when the music switched, but I close my eyes and breathe, enjoying the familiarity of the song as it pulls me home, drags me back to center.

Back to me.

I don’t know that dancing fixes anything. I don’t feel magically happy because of it. My problems don’t disappear when the music ends. But I understand life better when I dance, and understanding is half the fight of surviving.

Chapter 7

Carson

My Monday begins bright and early with a six A.M. workout. I manage to make it through most of the morning without picking up my phone. Almost to lunch. That’s better than yesterday.

I’m sitting in my environmental science class, but I gave up taking notes three minutes ago, and instead I’m staring at my old text messages, wishing I could reply to the texts Dallas sent me Saturday.

Getting to know her had seemed harmless on Friday, but when I woke up the next day and skipped my usual morning run to wait around until it was an acceptable hour to text her . . . that’s when I realized what a monumentally bad idea contacting her again was.

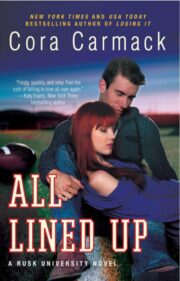

"All Lined Up" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All Lined Up". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All Lined Up" друзьям в соцсетях.