The world wastes no time in reminding me exactly why I shouldn’t be getting distracted by girls or parties or anything like this.

“Wouldn’t you like to know, Abrams.” I look around at the rest of the team members. The new coach is strict about inappropriate conduct, so I’m surprised there are this many players here and at how wasted they all are. They take shit for granted . . . things I would kill for. But I’m used to feeling that way. Growing up poor makes you hyperaware of all the other things people take for granted. But in this case . . . it might eventually work to my advantage. Let them rest on their laurels. It makes it that much easier for me to catch up. “I’m heading out. See you guys at practice.”

I hear some calls at my back, some asking, some daring me to stay and party with them. I just wave a hand and head for the door.

And maybe I’m borrowing trouble, but as I head for my truck, I type out a quick text.

Still thinking of that list.

Dallas’s reply comes a minute later, and I settle in behind the steering wheel, not bothering to turn the key in the ignition.

Who is this? Carson?

I hope there are not any other guys

out there making a list like this one.

And if there are?

I’ll just have to make sure my list is

better.

Maybe I should make a list of my own.

Maybe we should make one together.

Maybe we will.

Chapter 6

Dallas

Stella kept me out late again on Saturday (thankfully not at another party, but at the coffee place just off campus). Even after we turned out the lights for bed, we stayed up a while longer talking across the small space that separated our twin beds. Because of that, I snooze two too many times, making me a few minutes late for church on Sunday morning. When I squeeze past Dad sitting in his usual spot at the end of a pew a few rows from the back, his gaze turns steely.

I knock a hymnal off the shelving on the back of the pew, and it thumps against the carpet, drawing even more attention to my late entrance as the youth minister finishes greeting the congregation. Dad shifts, flexing his fists on his knees, and I rush to pick up the book and plop myself down beside him.

That would normally be the end of it. I would sit incredibly still until all the eyes left me, but somehow in my rush to sit down, I ended up with a few stray strands of hair in my mouth. I claw at my cheeks, trying to find the offending hairs and pull them away.

Dad makes a low grumbling noise that reminds me of a grizzly bear.

I show him my teeth in a grimace barely passable as a smile. If he wants a proper and polite daughter, he shouldn’t have spent my childhood dragging me to places where I was predominantly surrounded by men.

I fix my gaze straight ahead, taming my hair and clothes just in time for the youth minister to say, “We’re so glad to have you all this morning. Please take a few moments to greet your neighbors and say a warm hello to any new faces.”

The pianist and the organist start an upbeat version of “Joyful, Joyful,” and I wish that I had managed to be just a few minutes later. Maybe it makes me heartless, but this is my least favorite part of church. Dad and I are immediately inundated with former players and parents of players and teachers. It used to be that they all wanted to stay on good terms with Dad so that their kids would get more playing time. I had hoped that Dad’s new job might make us a little less popular, but no luck there.

Dad’s all smiles, shaking hands and laughing, his loud voice carrying and no doubt drawing more people toward us. I stand there awkwardly, smiling (horrendously fake) smiles and nodding along like I know a good daughter should. Mostly the men talk to Dad, and the women talk to me since there’s no mom to play that role. I get compliments on my hair (which I know is a hot mess because it’s hella windy outside) and my outfit (which is lined with wrinkles and smells of Febreze since I just grabbed it off the floor of my dorm room).

And of course . . . there are the questions.

“How’s college?”

“Have you settled on a major?”

“How are your classes?”

“How does it feel to be all grown-up?”

Plus a few questions about Dad and the university team, like I know or give a crap about that.

On the surface I’m all Oh, haha. I’m great. Loving it. Everything’s great. Just great. Hah. Hah. And underneath I’m like Dear God, why is this hymn SO LONG?

It’s the college inquisition, and it’s enough to make any recent graduate vow never to visit home again. Unfortunately for me . . . I don’t have that option.

One year. Two, tops. Then I’m getting out of here. I have to.

I shoot Mrs. Dunlap at the piano a desperate look, not just because I want her to speed up, but also because she’s one of the few people in this building that I actually want to talk to. In addition to playing the piano during the service and teaching the second-grade Sunday school class, she’s been my dance instructor since Dad and I moved here four and a half years ago.

The youth minister steps up to the pulpit once more, and people begin making their way back to their seats. I let out a sigh of relief when he tells us to bow our heads.

I try to listen, but I zone out not long after “Dear Heavenly Father.”

There’s too much quiet in prayers, too much time for my mind to wander. I think about how miserable it was to roll out of bed this morning and watch Stell go right on snoozing while I struggled to kick-start my day. Then I feel guilty for thinking I’d rather be sleeping during church . . . during a prayer, no less. But that only makes me think about the other things I feel guilty for . . . like the seriously hot stranger-danger make-out session I had two nights ago. Then I chastise myself over feeling guilty about something that in the grand scheme of things isn’t really that bad. But then the minister says, “Amen,” and I concede that while kissing someone isn’t bad, thinking about it when I’m supposed to be communing with the big guy upstairs probably isn’t winning me any bonus points.

We stand to sing a hymn, and even though the words are written up on a big screen hanging above the pulpit, I grab a hymnal so that I’ve got something to do with my hands. I follow along in the book, but don’t sing myself. I sound like a hyena on my good days (a hyena in the jaws of a lion on my bad days), and I’m too self-conscious that other people will hear me.

I hear Carson calling me a daredevil, and God, how wrong he was. If I were a daredevil, I would have said screw Dad and auditioned for real dance programs instead of caving to what he thought was best (and what his money provided). I would have found a way to make it all work—the auditioning and the moving and the money. That’s what daredevils do. I also wouldn’t have run off like a timid preteen when Stella caught us together. As if that weren’t pathetic enough, I’d then lied to Stella and told her that maybe I’d had a few drinks after all.

Because, of course, that was the only explanation for me doing something fun and out of character like actually hooking up with a guy.

A guy who didn’t answer either of the texts I sent him yesterday. Clearly he’d gotten over the fascination he’d had with me on Friday night. Maybe he’d been drunk.

I don’t know if I always hate myself this much and I never think about it, or if it’s a product of the reflection that’s inherent in church and religion and being wildly unsuccessful at growing up. Feeling like everyone around me can see the failure written across my forehead certainly doesn’t help either.

I sigh, and when Dad shifts next to me I catch him looking at me from the corner of his eye. I can’t tell if he’s disappointed or worried or annoyed.

Dad really only has two faces: normal and pissed.

And football. Football kind of gets its own expression, though it overlaps with pissed a lot.

Eventually, we return our hymnals to their holding places and take a seat for the sermon. I’ve given up the pretense of paying attention, choosing instead to doodle little dancers in the margins of the church bulletin.

The preacher calls all the little kids up to the front, where he does a short little minisermon for the kids before sending them out for children’s church. It’s usually a parallel for the more complex message he’ll give the rest of us. And I find myself thinking that church is like my kid’s sermon . . . it parallels my life as a whole. I show up, but I’m not in it. I go through the motions, but my mind wanders elsewhere. I dress and behave in the ways I know won’t get me in trouble. I get by. I bide my time waiting for the moment when it all ends.

But life isn’t church. It isn’t one hour during one day in the week. It’s everything, and I’m wasting it.

By the time the service ends half an hour later, I’m awash with emotions, anger and guilt and bitterness swallowing up whatever hope I manage to conjure. As soon as the benediction ends, I slip past Dad before he stands, mutter, “Be right back,” and flee before he’s inundated. As I walk away I hear Mrs. Simmons, whose daughter I went to school with, say, “You know, our youngest is shaping up to be quite the receiver. He’s just in eighth grade, but I’m sure he’ll make varsity as a freshman. Maybe you’ll be seeing him at Rusk in a few years.”

I resist the urge to roll my eyes. In Texas, everyone is a wannabe coach. Levi used to have strangers hand him plays they’d drawn up “just in case he wanted to try something new.” I pass Levi’s parents gathering their things from the second row, where they’ve sat for as long as I’ve known them. I smile politely and nod as I go.

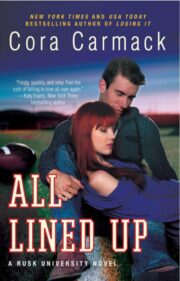

"All Lined Up" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "All Lined Up". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "All Lined Up" друзьям в соцсетях.