Theresa went back to her window. The afternoon had gone dark for her. She was trembling too. What was the matter? What was wrong? Something was horribly, fatally wrong.

At last Mary got up, with difficulty, made the distance to the table where her family sat, and let herself subside into a chair that was away from them: she was not part of them.

Now the four were taking in that bundle of letters in Mary’s hand.

They sat quite still, looking at Mary. Waiting.

It was for her to speak. But did she need to? Her lips trembled, she trembled, she appeared to be on the verge of a faint, and those young clear accusing eyes moved still from one face to another. Tom. Lil. Roz. Ian. Her mouth was twisted, as if she had bitten into something sour.

‘What’s wrong with them, what’s wrong?’ thought Theresa, staring from her window, and whereas not an hour ago she had decided she could never leave this coast, this scene of pleasantness and plenitude, now she thought, I must get away. I’ll tell Derek, no. I want to get out.

Alice, the child on Roz’s lap, woke with a cry, saw her mother there, ‘Mummy, Mummy,’ – and held out her arms. Mary managed to get up, steadied herself around the table on the backs of chairs, and took Alice.

Now it was the other little girl, waking on Lil’s lap. ‘Where’s my mummy?’

Mary held out her hand for Shirley and in a moment both children were on her knees.

The little girls felt Mary’s panic, her anger, sensed some kind of fatality, and now tried to get back to their grandmothers. ‘Granny, Granny,’ ‘I want Granny.’

Mary gripped them both tight.

On Roz’s face was a small bitter smile, as if she exchanged confirmation of some bad news with someone deep inside herself.

‘Granny, are you coming to fetch me tomorrow for the beach?’

And Alice, ‘Granny, you promised we would go to the beach.’

And now Mary spoke at last, her voice shaking. All she said was, ‘No, you will not be going to the beach.’ And, direct to the older women, ‘You will not be taking Shirley and Alice to the beach.’ That was the judgement and the sentence.

Lil said tentatively, even humbly, ‘I’ll see you soon, Alice.’

‘No you won’t,’ said Mary. She stood up, a child on either hand, the bundle of letters thrust into the pocket of her slacks. ‘No,’ she said wildly, the emotion that had been poisoning her at last pulsing out. ‘No. No, you won’t. Not ever. You will not ever see them again.’

She turned to go, pulling the children with her.

Her husband Tom said, ‘Wait a minute, Mary.’

‘No.’ Off she went down the path, as fast as she could, stumbling and pulling the children along.

And now surely these four remaining, the women and their sons, should say something, elucidate, make things clear? Not a word. Pinched, diminished, darkened, they sat on, and then at last one spoke. It was Ian who spoke, direct to Roz, in a passionate intimacy, wild-eyed, his lips stiff and angry.

‘It’s your fault,’ he said. ‘Yes, it’s your fault. I told you. It’s all your fault this has happened.’

Roz met his anger with her own. She laughed. A hard angry bitter laugh, peal after peal. ‘My fault,’ she said. ‘Of course. Who else?’ And she laughed. It would have done well on the stage, that laugh, but tears poured down her face.

Out of sight down the path, Mary had reached Hannah, the wife of Ian, who had been unable to face the guilty ones, at least not with Mary, whose rage she could not match. She had let Mary go up by herself and she waited here, full of doubt, misery and reproaches that were beginning to bubble up wanting to overflow. But not in anger, no, she needed explanations. She took Shirley from Mary, and the two young women, their children in their arms, stood together on the path, just outside a plumbago hedge that was the boundary for another café. They did not speak, but looked into each other’s faces, Hannah seeking confirmation, which she got. ‘It’s true, Hannah.’

And now, the laughter. Roz was laughing. The peals of hard laughter, triumphant laughter, was what Mary and Hannah heard, each harsh loud peal lashed them, they shrank away from the cruel sounds. They trembled as the whips of laughter fell.

‘Evil,’ Mary pronounced at last, through lips that seemed to have become dough or clay. And as Roz’s final yells of laughter reached them, the two young women burst into tears and went running away down the path, away from their husbands, and their husbands’ mothers.

Two little girls arrived at the big school on the same day, at the same hour, took each other’s measure, and became best friends. Little things, so bravely confronting that great school, as populous and busy as a supermarket, but filled with what they already knew were hierarchies of girls they felt as hostile, but here was an ally, and they stood holding hands, trembling with fear and their efforts to be brave. A great school, standing on its rise, surrounded by parkland in the English manner, but arched over by a most un-English sky, about to absorb these little things, babies really, their four parents thought – enough to bring tears to their eyes! – and they did.

They were doughty, quick with repartee, and soon lived down the bullying that greeted new girls; they stood up for each other, fought their own and each other’s battles. ‘Like sisters,’ people said, and even, ‘Like twins.’ Fair, they were, with their neat gleaming ponytails, both of them, and blue-eyed, and as quick as fishes, but really, if you looked, not so alike. Liliane – or Lil – was thin, with a hard little body, her features delicate, and Rozeanne – Roz – was sturdier, and where Lil regarded the world with a pure severe gaze, Roz found jokes in everything. But it is nice to think, and say, ‘like sisters’, ‘they might be twins’; it is agreeable to find resemblances where perhaps none are, and so it went on, through the school terms and the years, two girls, inseparable, which was nice for their families, living in the same street, with parents who had become friends because of them, as so often happens, knowing they were lucky in their girls choosing each other and making lives easy for everyone.

But these lives were easy. Not many people in the world have lives so pleasant, unproblematical, unreflecting: no one on these blessed coasts lay awake and wept for their sins, or for money, let alone for food. What a good-looking lot, smooth and shiny with sun, with sport, with good food. Few people anywhere know of coasts like these, except perhaps for brief holidays, or in travellers’ tales like dreams. Sun and sea, sea and sun, and always the sound of waves on beaches.

It was a blue world the little girls grew up in. At the end of every street was the sea, as blue as their eyes – as they were told often enough. Over their heads the blue sky was so seldom louring or grey that such days were enjoyable for their rarity. A rare harsh wind brought the pleasant sting of salt and the air was always salty. The little girls would lick the salt from their own hands and arms and from each other’s too, in a game they called, ‘Playing puppies’. Bedtime baths were always salty so that they had to shower off the bath water with water coming from deep in the earth and tasting of minerals, not salt. When Roz stayed over at Lil’s house, or Lil at Roz’s, the parents would stand smiling down at the two pretty imps cuddled together like kittens or puppies, smelling now they were asleep not of salt but of soap. And always, throughout their childhoods, day and night, the sound of the sea, the gentle tamed waves of Baxter’s sea, a hushing and a lulling, like breathing.

Sisters, or, for that matter, twins, even best friends, suffer passionate rivalries, often concealed, even from each other. But Roz knew how Lil grieved when her breasts – Roz’s – popped forth a good year before Lil’s, not to mention other evidences of growing up, and she was generous in assurances and comfort, knowing that her own deep envy of her friend was not going to be cured by time. She wished that her own body could be as hard and thin as Lil’s, who wore her clothes with such style and ease, whereas she was already being called – by the unkind – plump. She had to be careful what she ate, whereas Lil could eat what she liked.

So there they were, quite soon, teenagers, Lil the athlete, excelling in every sport, and Roz in the school plays, with big parts, making people laugh, extrovert, large, vital, loud: they complemented each other as once they had been as like as two peas: ‘You can hardly tell them apart.’

They both went to university, Lil because of the sport, Roz because of the theatre group, and they remained best friends, sharing news about their conquests, and making light of their rivalries, but their closeness was such that although they starred in such different arenas, their names were always coupled. Neither went in for the great excluding passions, broken hearts, jealousies.

And now that was it, university done with, here was the grown-up world, and this was a culture where girls married young. ‘Twenty and still not married!’

Roz began dating Harold Struthers, an academic, and a bit of a poet, too; and Lil met Theo Western, who owned a sports equipment and clothes shop. Rather, shops. He was well off. The men got on – the women were careful that they did, and there was a double wedding.

So far so good.

Those shrimps, the silverfish, the minnows, were now wonderful young women, one in a wedding dress like an arum lily (Liliane) and Roz’s like a silver rose. So judged the main fashion page of the big paper.

They lived in two houses in a street running down to the sea, not far from the outspit of land that held Baxter’s, unfashionable but artistic, and, by that law that says if you want to know if an area is going up, then look to see if those early swallows, the artists, are moving in, it would not be unfashionable for long. They were on opposite sides of the street.

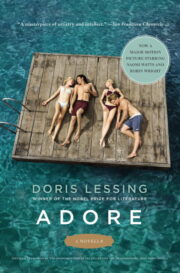

"Adore" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Adore". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Adore" друзьям в соцсетях.