The Grand Hotel Saint-Louis. The small court with its tables and metal chairs. Shutters of inside rooms pushed open through a wall of dense ivy. Grillwork is buried within it, forgotten balconies. Above, a section of the sky of Autun, cold, clouded. It’s late afternoon—the green is trembling, the smallest tendrils dip and sway. That penetrating cold of France is here, that cold which touches everything, which arrives too soon. Inside, beneath the coupole, I can see the tables being set for dinner. The lights are already on in the marvelous, glass consoles within which the wealth of this ancient town is displayed: watches in leather cases, soup tureens, foulards. My eye moves. Perfumes. Books of medieval sculpture. Necklaces. Underwear. The glass has thin strips of brass like a boat’s running the edges and is curved on top—a dome of stained fragments, hexagons, hives of color. Behind all this, in white jackets, the waiters glide.

Small, mirthless town with its cafés and vast square. New apartments rising on the outskirts. Streets I never knew. There are two cinemas, the Rex and the Vox. Water is falling in the fountains. Old women are walking their dogs. Morning. I am reading An Illustrated History of France. There’s a dense mist which has turned the garden white, in which everything is concealed. An absolute quiet. I hardly notice the passing of time. When I go out, the sun is just burning through. The spire seems black. The pigeons are grumbling. There’s always the desire to talk to somebody about this time, I can’t escape it. I start out beneath the long, sulking flank of the cathedral and then begin descending. I know all the streets. Place d’Hallencourt. Rue St. Pancrace, curving down like a woman. I know the fine houses. And, of course, I know some people. The Jobs—she’s the thinnest woman I think I’ve ever seen. The waitress at the Café Foy. Madame Picquet. Now, that—I have to ask Wheatland about her.

[3]

THE ELEVATOR RISES, HUSHED, to a splendid apartment above the Avenue Foch. The rooms are filled with people, some of them in evening clothes. The Beneduces have given a small dinner. Everyone else was invited to come by afterwards. Two waiters in white jackets are serving coffee. I stand near the window. Below, through the dark and still fragrant trees, the traffic floats past on headlights. Paris seems wondrous to me now, even a little too rich. I’m strangely devout, I find myself defending the meager life of the provinces as if it were something special. It’s not like the life of Paris, I say, which is exactly like being on some great ocean liner. It’s in the little towns that one discovers a country, in the kind of knowledge that comes from small days and nights.

“There’s Anna Soren,” Billy whispers.

She has been a famous actress, I recognize her. The debris of a great star. Narrow lips. The face of a dedicated drinker. She constantly piles up her hair with her hands and then lets it fall. She laughs, but there is no sound. It’s all in silence—she is made out of yesterdays. He is pointing out Evan Smith, whose wife is a Whitney. There are girls who work in the fashion houses, publishing. One meets a certain kind of people here, people with money and taste.

“Definitely.”

“There’s Bernard Pajot.”

Pajot is a writer, short, the face of a cherub with moustaches, enormously fat. His life is celebrated. It begins in the evenings—he sleeps all day. He lives on potatoes and caviar, and a great deal of vodka. He not only looks like, they say he is Balzac.

“Does he write like him?”

“It’s enough of a job looking like him,” Beneduce confides.

I overhear Bernard Pajot. His voice is deep and richly hoarse. He smokes a thin, black cigar.

“Last night I had dinner with Tolstoi…” he says.

Behind him are tiers of fine books laid on glass shelves and illuminated from below like an historic façade.

“…we were talking about things that no longer exist.”

Beneduce is a journalist, a bureau chief. Straight, brown hair which he wears a little too long, blue eyes, unerring knowledge. He has the calm irreverence one achieves only from close observation of the great. And he knows everybody. The room is filled with marvelous languages. People from Switzerland. People from Mexico. His wife is a lynx. Even from across the room she imposes her assurance, her slow smiles. She’s a friend of Cristina’s, I know her from afternoons on the boulevard. I see her leaving cafés. She favors knit suits, her breasts moving softly within them, but I don’t think she meets men. Her husband is too potent. He could cut them to pieces. He’d know exactly how to do it.

She’s talking to Billy. He’s very elegant, very slim. Hair, I notice, turning grey along the sides. Everything else has become gold, the chaste gold of cufflinks, a gold watchband, the mesh dense as grain, a gold lighter from Carrier. I don’t know what they’re talking about, nothing, I’m sure it’s nothing because I’ve had a thousand conversations with him myself, but still he can hold her there somehow, Billy, to whom Cristina used to whisper in those early days that she wanted to leave the party and go make a little boom-boom. He has that white line of a scar on his mouth. One’s eyes always fall to it. He lights her cigarette. Her head is bent forward a little. Now it straightens up. They continue to talk. I notice she’s never really still. She seems to writhe in one’s gaze with slight, almost imperceptible movements.

I wander away towards more quiet regions of the apartment which is very large. The ceilings become silent, the voices fade. It seems I am entering an older, a more conventional household. The dining room is empty and dark. The table is just as it was, not cleared. The cloth is still spread on it, the chairs are in disarray. Glass plates bear the remnants of brie and the halves of pears already becoming brown. In front of the windows is a zone of tall plants, a conservatory through which noise does not penetrate, through which, in the daytime, the light diffracts. It is a room in which I can imagine the silence of leisurely mornings, the pages of Le Figaro turning softly as Maria Beneduce glances over them, the pages of the Herald Tribune. She is in a short robe printed with flowers. She drinks black coffee stirred with a tiny spoon. Her face is natural and unpainted. Her legs are bare. She is like a performer backstage. One loves this ordinary moment, this pause between the brilliant acts of her life.

Suddenly someone is behind me.

“Did I scare you?” Cristina says, smiling.

“What? No.”

“You jumped about a foot,” she says. “Come on, I want you to meet somebody.”

A friend from Bristol, Tennessee, she tells me as she leads me back. No, but I’m going to like her, she’s very funny. She’s married to a rich, rich Frenchman. She puts flowers in all the bidets. He gets furious. Already I dread her.

People are still coming in, even this late, appearing after other dinners, the theatre. Beneduce is guiding a handsome trio into the room, a man and two stunning women in suede boots and tightly belted coats. Mother and daughter, Cristina tells me. He’s marrying them both, she says. Near the bar Anna Soren listens to the conversation around her with a wavering, a translucent smile. She doesn’t always know who’s speaking. She looks at the wrong person. Her false eyelashes are coming loose.

“You know something?” Cristina says. “You’re the only friend of Billy’s I like.”

It pleases but disturbs me, this remark. I’m not sure what it means, I just have the feeling it will prove to be fatal. I don’t want to answer or even to appear as if I’ve heard.

“They’re all illiterates,” she tells me.

Through the crowd a woman is approaching.

“Isabel!” Cristina cries. It’s her friend.

There is no way to begin except with admiration for Isabel who is forty and dressed in a beautiful, black Chanel suit with silver buttons and a ruffled, white shirt. On her finger is a ring with a large diamond, a perfectly round diamond that catches every piece of light, and her smile is as dazzling as her clothes. There’s a young man with her whom she introduces.

“Phillip…” Her hand flutters hopelessly, she’s forgotten his name.

“…Dean,” he murmurs.

“I’m the worst in the world,” she says, the words drawling out. “I just seem to forget names as fast as people can tell them to me.”

She laughs, a high, country laugh.

“Now, don’t take it to heart,” she tells him. “You’re the best-looking thing in this room, but I’d forget the name of the President himself if I didn’t already know it.”

She laughs and laughs. Phillip Dean says nothing. I envy that silence which somehow doesn’t disgrace him, which is curiously beautiful, like a loyalty we do not share.

“He’s been traveling in Spain,” she says, “isn’t that right?”

“Spain!” Cristina says.

His face seems to show it. There still remain the faint, lustrous tones of journeys in an open car.

“I love Spain,” Cristina says.

“You’ve been there?”

“Oh,” she says, “many times.”

“Barcelona?”

“I love it.”

“And Madrid…”

“What a city.”

“We went to the Prado every day,” he says.

“I love the Prado.”

“What is it?” Isabel says.

“The museum.”

“The museum?” she says. “Why, I love it, too. I forgot what it was called.”

“It’s the Prado,” he says.

“Why, that’s right. I remember it now.”

“What were you doing in Spain?” Cristina asks.

“I was just traveling,” he says.

“All alone?”

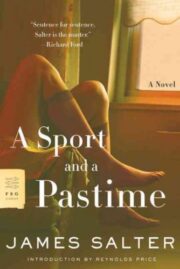

"A Sport and a Pastime" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Sport and a Pastime". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Sport and a Pastime" друзьям в соцсетях.