They climb the stairs. She goes first, as always. Her calves flash before him, turning away, rising on the narrow treads. Her key opens the door. Dean’s prick begins to stir, and as he doubles the pillow later and she rises on her elbows, his mind is already cut loose and wandering as if he cannot keep himself together. He is thinking of what it will be like without her. He cannot repress it. Like the cough of a sick man, a weakness rises to frighten him, an invisible flaw, and he embraces her with a sudden, dumb intensity. Her back, even the word for it is beautiful, dos, lies beneath him, the back she never sees, the smooth intelligent back upon which, like a table, he has gazed for so many hours. He rears in the darkness to admire it. He had forgotten. Every minute of the day seems to have converged. He wants to slow them, to have this sweet ending last.

[28]

OVER FRANCE A GREAT summer rain, battering the trees, making the foliage ring like tin. The walls grow dark with water. The gutters are running, the streets all abandoned. It started at dusk. By nine it is still pouring down.

They are in Dole. They stare out the window of a plain café where they have been sitting for an hour or more. Across from them is an empty park, not very large. In it a strange apparatus is being erected. A high wire. Two tall poles have been guyed to the ground. Men are still working in the rain, testing the lights. From time to time the façade of buildings opposite appears in the blue floods, but the wire itself, strung in the upper dark, is invisible. Over the rooftops, like flowers, fireworks burst without sound.

It’s a local fête. There would have been a crowd, but the rain has kept them away. Only a few families huddle beneath the awnings now. Others sit inside cars. The lights go off again. The square is in darkness.

The café is not empty. There’s a table with three men and also, in a raincoat, white legs showing beneath it, the acrobat, who waits at the bar. His face is hard. He’s been there for a long time. After a while, the patron offered him a drink. Merci. The glass is empty now. He stands there quite alone, a man in his thirties, the coat hung over his shoulders.

In a low voice running like a secret, Anne-Marie begins to describe him. He comes from the city, a poor section of Paris, she knows it well. He has a daughter, she explains, a little girl who travels with him, the mother has run away. They journey all over France together, only the two of them. The cheapest hotels. The little girl has no friends, just her father, and for toys a single doll. She’s always quiet. She never speaks. Dean doesn’t recognize this famous story. He glances at the weary face of the man; upstairs the child is sleeping. It’s all bitterly real to him, a fiction for which a place already existed in his heart.

Outside, they have finished the preparations. They come into the café to say this. Somehow the acrobat seems strangely disinterested, nor do they stay to keep him company. One has the feeling that someone else exists, an impresario, an unseen man whom they all obey.

The acrobat has accepted another drink. Dean watches cautiously, afraid of what he sees. Premonitions of disaster come over him. The entire machinery: strings of colored lights along the guy wires, the slender poles rising high into darkness, the invisible platforms—it is all a death they are arranging. He is certain of it. He can feel it in his chest.

The acrobat has said nothing, not a word. He has hardly moved. One loves him for this passivity, this resignation, and for his face which has a gypsy darkness. If it continues to rain there can be no performance, and the rain falls heavily, seldom shifting, drumming on the drenched cloth of the car outside. Only a few people still wait.

Dean counts out the money for the bill. The franc pieces seem unusually bright. He lays them in the saucer. They make a little clicking sound, like teeth, a clear sound, and in that instant he becomes aware it has been heard by, has awakened the solitary dreamer at the bar—he glances up but no, the acrobat has not noticed. He is gazing into the mirror. His white-stockinged legs, powder white, are crossed at the ankle. His slippers are frayed, but he is more than he seems, this man. He is an agent, an emissary. He has selected a disguise in which he moves nervously, white as a moth in the spotlight above the common crowds, but it is all a conceit. He is far more important than that. Dean knows this. He recognizes it—impossible to explain. It really does not even concern her. It is all meant for him, and when it is announced that the performance has been cancelled, Dean receives the news without surprise. It makes no difference. The performance itself was incidental.

“Wait here,” he says. “I’ll get the car.”

He vanishes into the rain. Anne-Marie stands just inside the door until the car pulls up with that vast, irregular grace, its headlights yellow and reflecting in the windows of the café, the wipers ticking slowly. She runs for it. He leans across the seat to hold the door open. His face is wet, his hair. She gets in hurriedly.

“What rain!” she says.

Dean doesn’t drive off. Instead, he tries to look through the running glass, to see inside the café one last time. The bar is empty. The acrobat has gone.

They drive through the streets of an unknown town. The rain pours down like gravel. In the green light of the instrument panel he feels as homeless, as desolate as a criminal. Gently she wipes his wet cheeks with her fingers. They have nowhere to go. They are strangers here, the doors of the town are closed to them. Suddenly he is filled with intimations of being found somehow, of being seized and taken away. He doesn’t even have a chance to talk to her. They are separated. They are lost to each other. He tries to cry out in this coalescing dream, to tell her where she should go, what she should do, but it’s too complicated. He cannot. She is gone.

A genuine desperation overwhelms him. He hasn’t the money to really go off with her. They are imprisoned in the smallness of Autun, a night or two away doesn’t matter, and now, yes, he knows it, they have been discovered. Dean is sure of this. And I, too, in retrospect, I see he was right. The acrobat has disappeared into the villages of France, into the night of all Europe, perhaps. The Delage is alone on the streets. One need not follow as it crawls through the darkness—it can be recognized anywhere.

Dean is dispirited. In the hotel room he undresses carefully, laying them down as if the clothes are not his, as if they are to be burned. The night is cool with all its rain and a chill passes over his nakedness. He feels lean as an orphan. The past has vanished and he fears the future. His money is lying on the table, and in the dark he goes over to count it, the paper bills only. He lifts the folded notes. The coins spill off, and one falls to the floor, rolls away. He listens but cannot tell in which direction it has gone. Anne-Marie comes up behind him, naked too, and suddenly he is transfixed, like a hare in the headlights of a car. Her arms steal around him. Her body touching him, the points of her breasts, the soft bed of hair, is a virtual agony. They caress one another, pale as embryos in the dark.

She wants to be arranged over a chair. Dean finds one. She bends over it. Her breasts hang sweetly, like the low boughs of a tree, like handfuls of money. His hands slide to her waist which is narrow. He begins slowly, and she breathes as if sinking into a bath. From without is the sound of pouring rain.

In the morning it is calm. He awakens as if a fever has passed. Europe has returned to its real proportions. The immortal cities swim in sunlight. The great rivers flow. His prick is large and her hand moves to it as soon as her eyes open. He searches his clothing for the crumpled, leaden tube. He hands it to her. She looks at it impassively. He kicks the covers away as she unscrews the cap. She begins to spread it on. The coolness makes him jump. Afterwards she rolls over and in the full daylight he slowly inserts this gleaming declaration. Her forehead is pressed to the sheet. Her eyes are closed. Dean barely notices. Finally he is entered all the way. He lies still.

“Would you like to read?” he says.

“Comment?”

“Read. A magazine.”

“Yes,” she answers vaguely.

They move to the edge of the bed. There is an old copy of Réalités. He reaches for it and pulls it to the floor. Her head leaning down, she starts to turn the pages. Dean looks over her shoulder. It is Sunday morning. Ten o’clock. Only the occasional, soft leafing of paper interrupts the stillness. She has come to an article about the paintings of Bonnard. They read it together. He waits until she has finished the page. Gently he begins.

“Not enough graisse,” she says.

He withdraws carefully—she is almost clinging to him, it feels—and she applies a bit more, wiping her fingers afterwards on the sheet. In it goes—she lies calm—and intrigued by a page that shows photographs of the fourteen kinds of feminine appeal (innocence, mystery, naturalness, etc.), he begins to move in and out in long, delirious strokes. France is bathed in sunshine. The shops are closed. Churches are filled. In every town, behind locked doors, the restaurants are laying their tables, preparing for lunch.

[29]

THE MORE CLEARLY ONE sees this world, the more one is obliged to pretend it does not exist. It was strange how I found myself almost completely silent when I was with her. There was everything to talk about it seemed, but we simply could never begin. I took her to dinner in May when Dean went to Paris for a few days, and what days they were, summery, vast. The light failed slowly. The world was filled with blue cities, fragrant, mysterious. We dined at the hotel. From time to time I smiled at her, like a stupid uncle, while she talked about Dean. I was really not too interested. The terms of the encounter were all wrong. I knew what she was. I was ready to confess, to fall to my knees like a believer. It would have been a terrible moment. She would have denied it all. More likely, she wouldn’t have understood. What she wants is to know what his father and sister will think of her. Will they find her nice?

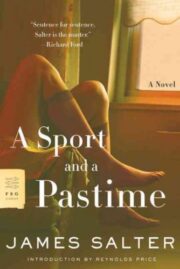

"A Sport and a Pastime" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Sport and a Pastime". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Sport and a Pastime" друзьям в соцсетях.