Around the Champ de Mars a green Oldsmobile is turning, black soldiers inside. They are wearing sunglasses. My blood jumps. I can see them as they go by, very slowly, not talking, taking it all in. They are going to recognize me, suddenly I’m certain of it. I can’t look at them. The negro lover who has been seeking her for months has finally arrived. The car is going to stop across the street from the café and three men step out, lazily slamming the doors. The fourth remains in the back seat. My mind is racing. Is it him? Is he the one to whom she will be delivered? Dean is pushing someone. There’s a scuffle among the chairs.

Of course, it never happens. I have invented it all, their vengeance, their slow, deliberate walk. Instead, they drive slowly around the square, turning, turning. I become calm as I see them stop near the direction signs, read, and then head off on the road to Dijon.

The darkness has come down, and they walk in its fragrance. They reach her street. In the fruit store the lights are still on. The Corsicans are drinking. They’re in their undershirts, passing a bottle of wine back and forth as they sit half-buried among the crates. The floor is covered with newspapers. One can hear them laughing. A cat slips out the door.

“They’re very nice,” Anne-Marie says. “I pass them on the stairs. They always stand aside.”

They’re all sons, dark, the short hair curling out of their shirts.

“I find them good-looking,” she says.

She opens the door to her room. The key rattles. Dean is nervous. In his clothing he conceals, like an assassin, a small tube of lubricant—he would be frightened to have it seen. Still, it exists, cool as a surgical instrument. His answers are vague.

“I love the smell of the fruit,” she says.

She has opened the shutters. The room is darker than the night outside. Dean stands close behind her. She is quite naked. Air as cool as water washes over them.

“Can you smell it?” she asks.

“Yes.”

They lie in bed. The minutes seem somehow suspended. He feels she is waiting. He is afraid to recognize the moment.

“Do you want it that way?” he says. His voice sounds unfinished.

She was expecting it. She hesitates.

“Ne me fait pas mal.”

She watches in silence as he lays a thin coating on his prick. The strength seems to have left her. She behaves as if she has been condemned. He lowers himself carefully onto her back. He is determined to perform the most gentle act, but he doesn’t know exactly where to enter. He tries to find it.

“Plus haut,” she whispers.

His arms are trembling. Suddenly he feels her flesh give way and then, deliciously, the muscle close about him. He tries not to press against anything, to go in straight. She is breathing quickly, and as he withdraws on the first stroke he can feel her jerking with pleasure. It’s the short movements she likes. She thrusts herself against him. Moans escape her. Dean comes—it’s like a hemorrhage—and afterwards she clasps him tightly. He can feel faint annular twitches. He lies perfectly still until these final agonies, these quenching hugs which draw the last semen from him, subside. Then he withdraws. There is a tight, failing embrace of the head, then that, too, is gone. They have parted.

“Did you like it?” he asks.

“Beaucoup.”

[22]

A FEAST OF LOVE is beginning. Everything that has gone before is only a sort of introduction. Now they are lovers. The first, wild courses are ended. They have founded their domain. A Satanic happiness follows. They are off to Besançon on the weekend, filled with feathers, floating in pure joy. The spring road flies beneath them. She likes to talk about it. Tell me what you want, she says. I want to please you.

“I like it when you do,” he says.

“No,” she insists, “tell me.”

They walk in the park, submerged in a coolness like old walls. The benches are empty. They are alone. At this hour of evening the sun is gone. The sky, as if summoning itself for the last time, is a piercing, a pale blue, so clear it frightens. It seems that every sound has fled.

They walk without speaking, hip against hip. He feels an utter, a complete happiness. The dark fragrance of the trees washes down on them. Their shoes are dusty. The last light fails.

In the dining room they sit across the table from each other. The hotel is spacious and in need of small repairs. Dean is filled with a sense of certainty. It’s all familiar. He feels he has been here many times before. This is a returning. If he asks her to go upstairs after the soup, she will put her napkin on the table without hesitation. His eyes examine her face. She smiles.

The owners of the hotel, she points out, are probably pieds-noirs, Algerians. Dean looks around. The two young men behind the cashier’s desk are very dark. Maybe juifs, she adds.

“They don’t look it.”

“You can tell,” she says.

In the room she seems thoughtful. She takes her things off slowly.

“How is it that you are not married?” she asks.

Dean is protean. He is aware of his muscles, his teeth. Life seems to have saturated him, and yet he feels quite calm.

“Go slow,” she says.

“Oui.”

His devotion is complete; he is beginning to sense the confusion that arises from the first fears of what life would be like without her. He knows there can be such a thing, but like the answer to a difficult problem, he cannot imagine it.

There are many days now when he is perfectly willing to accept the life she illustrates, to abandon the rest. Simple, vagrant days. His clothes need pressing. There are flea-bites on his ankles.

“No,” she says. “Not fleas.”

“Listen, I know what they are.”

“There are no fleas in French hotels,” she says.

“Of course not.”

They stroll along the streets, pausing at shoe stores. He allows her to walk on a bit without him. She stops and turns. They stand this way, twenty feet apart. Then, slowly, he comes to her. They walk hand in hand. Her mother has invited them to lunch the first of April. Dean nods. It doesn’t alarm him.

“We can go?” she says.

“Yes, of course.”

“She wants to meet you.”

“Fine.”

He likes to start into her sometimes while she is talking. She falls still, the words floating down like scraps of paper. He is able to make her silent, to form her very breath. In the great, secret provinces where she then exists, stars are falling like confetti, the skies turn white. I see them in the near-darkness. Their faces are close. Her mouth is pale and tender, her lips unrouged. Her open body radiates a warmth one must be quite close to feel. They are discussing the visit to St. Léger. She describes it all. It’s very pleasant to arrange the day, the hour they will go, who they are likely to encounter. She talks about her parents, the house, the woman next door who always asks about her, the boys she used to go with. One has a Peugeot now, that’s not bad, eh? One has a Citroen. Her mother tells her about all the accidents—that’s what worries her most. Dean listens as if she were unfolding a marvelous story full of invention, a story which, if he wearies of it, he can suspend with the simplest of gestures.

[23]

A SPLENDID NOON, THE SKY flooded with light. They drive along the canal. St. Léger seems quiet and the house itself, as they approach it, empty. Anne-Marie jumps out. She’s seen her cat. She picks it up and carries it in her arms.

The meal is served in the kitchen. It begins with a kind of cheese pie. They watch to see if Dean will like it. It’s very chill in the room even though the day is warm. Perhaps it’s the tile floor, he thinks, or the walls—he isn’t sure. He nods at the conversation which he only half understands. His flesh feels blue. Suddenly he realizes he must be getting sick, but then her mother rises to get a scarf. As she sits down again she remarks that it’s a little cold. The father shrugs. Dean has been unable to exchange a word with him. They sit like strangers. It is Anne-Marie who talks, mostly to her mother and quite gaily, as if only the two of them were there. Occasionally she asks Dean if he understands. He tells her yes. The father sits like an Arab. He has a lean face. A long nose. He’s wearing a cap. He looks at the table or out the window. At one point his wife reaches over to pat his hand. He appears not to notice.

Dean feels increasingly nervous. He is sitting all alone. He doesn’t like to look at the father whose eyes are pale and watery, a convict blue. As for the talk, it washes across him like water. He no longer even hears familiar words.

“Phillip, did you understand?” she says.

“Oui,” he replies sleepily.

“Oui?” the mother asks, her bright gaze on him. For a moment he is afraid they are going to question him.

“Quelquefois,” Anne-Marie says, “il comprend très bien.”

The mother laughs. Dean lowers his head. He feels the unhurried gaze of the father on him. He tries to return it, is determined to, but involuntarily his eyes flicker away for an instant, and that is enough. It’s finished. He knows he has been measured. In revenge he begins to think of their daughter naked, images as unforgivable as slaps. The father lights a cigarette.

He tries once more to concentrate on what they are saying, but it’s all too fast. He hardly understands a word. Everything seems to have left him. He begins to count his forkfuls, then the wall tiles.

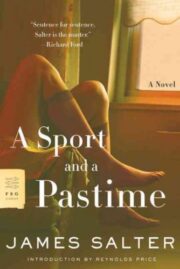

"A Sport and a Pastime" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Sport and a Pastime". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Sport and a Pastime" друзьям в соцсетях.