“I had better take you home, Duchess,” he said. “I need to call upon Vanessa and see if she is willing to make peace with me. Elliott wanted me to go there first, but I happened to hear the popular interpretation of my quitting London in the middle of the Season and felt compelled to set the record straight, especially when I discovered from your butler that you were walking in the park.”

“You must not keep her waiting any longer, then,” she said. “She has become my friend during the past two weeks.”

And they rode back to Dunbarton House to the astonishment and delight of everyone they passed in the streets—and to not a few pointed comments. Constantine lifted her down outside her door, waited while she ascended the steps, watched her disappear inside, and rode off.

Without another word.

If she had still had her parasol with her, Hannah thought as she climbed the stairs to her room, she would have bashed him over the head with it before leaving him.

One did not tell a woman that one was going to marry her and then fail to ask.

Not, presumably, unless one was Constantine Huxtable.

I suppose every man dreads the actual proposal scene of his own love story.

She heard the echo of those words of his and ran up the last few stairs.

His own love story.

And then she stopped abruptly. That scene he had enacted in the park was surely the most shockingly romantic thing that had ever happened to her. He could not possibly have done it simply to assert his masterdom over her.

He loved her.

She laughed aloud.

THE ROMANTIC GESTURES had not ended. The following morning, less than an hour after Barbara’s departure, when Hannah was feeling somewhat down in spirits, a single white rose was delivered to Dunbarton House. There was no card with it. At the same time a gigantic bouquet of multicolored flowers of all kinds arrived, done up with glossy yellow ribbons, complete with Hannah’s parasol and a flowery, amusing note from Lord Hardingraye, who could be as outrageously flirtatious as he wished without danger of being taken seriously because she knew—and he knew she knew—that in one essential respect he was of the same persuasion as her duke had been.

The bouquet was set on a table in the middle of the drawing room, to be enjoyed by all comers for days to come. The rose found its way to her bedchamber, where she alone would enjoy it.

An hour later the butler brought her a note on his silver salver. It had a brief message and no signature.

I lust after you.

Not so very romantic, perhaps, but Hannah smiled as she read it for perhaps the dozenth time—after ascertaining that its author had not delivered it in person and was not waiting in the hall below.

She recognized the beginning of a game.

She dined during the evening with the Montfords and enjoyed their company and conversation along with that of Mr. and Mrs. Gooding and the Earl and Countess of Lanting—the ladies were Lord Montford’s sisters.

The next morning a dozen white roses were delivered to Dunbarton House, again with no accompanying card. They were taken up to Hannah’s sitting room.

An hour later the butler came with a note atop his salver.

Again it was unsigned.

I am in love with you, it read.

Hannah held it to her lips, closed her eyes, and smiled.

The wretch. The absolute wretch. Did he have no respect for her nerves? Why did he not simply come?

But she knew the answer. He had been speaking the truth in Hyde Park—if you knew me better, you would understand that I am babbling, Duchess, and that my heart is thumping quite erratically.

The foolish man was nervous.

And long may it last even though the wait seemed interminable. Nervousness was making him quite the romantic.

She went to the opera during the evening with the Sheringfords and the Marquess of Claverbrook and sat with her hand on the sleeve of the latter for most of the evening while they exchanged remarks. The tenor brought tears to her eyes just with the beauty of his voice. The soprano brought tears to the marquess’s eyes just with her beauty. He chuckled low as Hannah laughed.

“But not with her voice?” she asked.

“That,” he said, “just gives me the headache, Hannah.”

Much of the attention of the audience was focused upon their box, and Hannah wondered idly if tomorrow’s gossip would be that she was digging her claws into yet another elderly, wealthy aristocrat. The thought amused her.

The following morning it was two dozen roses that arrived—blood-red roses. No note, of course. That came an hour later.

I LOVE YOU, it read, my multipetaled rose.

No signature.

Hannah wept and thoroughly enjoyed every tear.

She was supposed to go to Lord and Lady Carpenter’s Venetian breakfast during the afternoon. Contrary to the name of such entertainments, they were not morning affairs. It did not matter either way. She did not go.

She donned a dress she had worn only once about three years ago. She had not worn it again because it made her feel like a scarlet woman inside as well as out, and that was too blatant a disguise even for her. She loved it nevertheless, and today it matched her roses. She wore a single diamond on a silver chain about her neck—a teardrop that would not dry or lose its luster—and no other jewelry.

She waited.

There was no improving upon two dozen red roses.

There was no more to be said on paper either. He had even written the first three words of the last note in capital letters. The rest had to be spoken aloud, face-to-face.

If he could muster the courage.

Ah, her poor, dear devil. Tamed by love.

He would, of course, find the courage. And he would be quite splendid—when he came.

She waited.

Chapter 22

THIS LOVE BUSINESS, Constantine had discovered over the past several days, could quite unman a person. He had a new respect for married men, all of whom had presumably gone through the ordeal he was currently going through. With the exception of Elliott, of course, who had been proposed to, lucky man.

Reconciling with Vanessa had been easy.

“Don’t say a word,” she had said, hurrying across the drawing room of Moreland House toward him as soon as he had set foot inside it, while Elliott had stood by the fireplace, one elbow propped on the mantel, one eyebrow cocked in amusement. “Not a word. Let us forgive and forget and start making up for lost time. Tell me about your prostitutes.”

Elliott had chuckled aloud.

“Ex-prostitutes,” she had added. “And don’t you dare laugh at me, Constantine, just when we are newly friends again. Tell me about them, and the thieves and vagabonds and unwed mothers.”

She had linked her arm through his and drawn him to sit beside her on a sofa while Elliott had looked on with laughter in his eyes and on his lips.

“If you have an hour or six, Vanessa,” Constantine had said.

“Seven if necessary. You are staying for dinner,” she had told him. “That is already settled. Unless, that is, you have an engagement with Hannah.”

An unfortunate choice of words. And Hannah, was it?

“No,” he had said. “I have to work myself up to falling on one knee and delivering a passionate speech, and it is going to take some time. Not to mention courage.”

Elliott had chuckled again.

“Oh, but it will be worth every moment,” Vanessa had told him, her eyes shining, her cheeks flushed. “Elliott looked very splendid indeed when he did it. On wet grass, no less.”

Constantine had looked up reproachfully at his grinning cousin.

“It was after Vanessa had proposed to me,” he had said, raising his right hand. “I could not allow her to have the final word, now, could I? She said yes before I did.”

Theirs might be a story worth knowing, Constantine had thought.

In going impulsively to Dunbarton House within two hours of his return to town, he had hoped to settle the matter with Hannah. And then, when he had found her from home but had learned she was in Hyde Park, he had gone in pursuit of her and had seen—without having to stop and think—the perfect way of declaring himself.

It had not struck him that she might refuse to mount his horse with him. And indeed she had not done so.

It had not occurred to him that after she had done so and after he had kissed her quite lasciviously and in public, and she had kissed him back, she might then refuse to marry him.

Not that she had refused.

It was just that he had not asked.

And he had not even realized that until she had pointed it out. Dash it, there was all the difference in the world between asking and telling, and he had told.

Just like a gauche schoolboy.

Why was there not a university degree course in proposing marriage to the woman of one’s choice? Did everyone mess it up as thoroughly as he had done?

And so he had had to spend three days making amends. Or three days procrastinating. It depended upon whether one was being honest with oneself or not.

But once he had started, he had to allow the three days to proceed on their way. He could hardly rush in with his proposal after sending just one rose and the declaration that he lusted after her, could he?

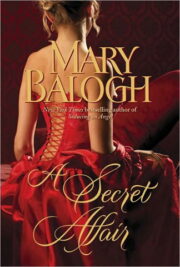

"A Secret Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Secret Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Secret Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.