Ladies, doctors caution that if one indulges in the habit of a heavy evening meal during the winter, one must have care to allow sufficient time to pass before entering the marital bed. The consequence of poor timing could result in a stroke.

—Honeycutt’s Gazette of Fashion and

Domesticity for Ladies

Keep reading for an excerpt from The Earl's Marriage Bargain by Louise Allen.

The Earl's Marriage Bargain

by Louise Allen

Chapter One

1st September, 1814

If she was in a novel written by her friend Melissa, then this post chaise would be rattling across the cobbles on its way to the Borders for a Scottish wedding and the seat next to her would be occupied by a dashing, dark and decidedly dangerous gentleman.

As this was real life, Jane was on the way to Batheaston to spend at least six months in disgrace with Cousin Violet. Beside her was Constance Billing, her mother’s maid. It had become clear ten minutes after their journey had begun that the only thing constant about Constance was her ability to sulk relentlessly and to disapprove of everything.

On the other hand, at least she was not being sent home to Dorset. Cousin Violet was entertainingly eccentric and—so she fervently hoped—Billing would be returning the morning after their arrival.

Jane consulted the road book. ‘We do not change horses at Kensington as it is not even two miles from London. Hounslow is the first halt, I believe.’

‘In that case, Miss Jane, why have we stopped?’

‘Because, as you can observe through the front glass, the traffic has become entangled for some reason.’ Jane half rose from her seat to look over the back of the pair of horses. ‘Ah, I see there has been an accident.’

The church was just ahead of them on the bustling main road through the village of Kensington and two large wagons were in front of it, apparently with their wheels locked. The drivers were both standing up, waving their whips and shouting at each other, which was not helping in the slightest. Fortunately, they were out of earshot. Passers-by and other drivers had stopped to offer advice, gawk or generally get in the way.

Jane dropped the window beside her and leaned out. Distantly behind them there was the sound of a horn. ‘That is either a stagecoach or the Mail is coming through.’

She settled back against the squabs and prepared to be entertained. Travellers complained about post chaises and their swaying motion, but they did have the benefit of a wide front window through which to survey the world. Naturally, Billing did not approve of all that glazing and kept her eyes averted from it. It was neither discreet nor private, in her opinion, and young ladies should not be looking around, risking attracting the roving eye of some rake or sauntering gentleman.

‘Do put up the glass, Miss Jane,’ Billing scolded. ‘There is a common alehouse just the other side of the pavement from us.’

She did have a point, Jane conceded. The Civet Cat opposite looked decidedly seedy and not at all like the well-kept, welcoming inns of the villages around her home.

As she mentally swept the frontage, cleaned the windows and added a pot or two of geraniums, the door of the alehouse burst open and three men rolled out, scattering pedestrians. They were followed by two others carrying clubs.

Billing gave a screech. ‘We’ll be murdered!’

‘No, we will not, but that man will be if someone doesn’t help him.’

The fight had resolved into one against four as the largest of the club-bearers dragged a tall, dark-haired man to his feet and held on to him as the others closed in and began to rain blows against head and body.

‘Why doesn’t somebody stop it? That is not a fight, that is a deliberate assault. They should call a constable.’

The tall man wrenched free, unleashed a punch and knocked down one of his attackers, sending him crashing into two of the others.

‘Oh, well done, sir! Hit him again, the bully!’

Jane ignored Billing tugging at her arm and shushing her. She opened the window in the door of the carriage, gripped the edge and held her breath because, despite that gallant punch, the man was held fast now by the two he had fallen against. He was shaking his head as though to clear it after a vicious blow and was clearly now no match for the fourth assailant who was advancing, grinning in obvious anticipation.

To Jane’s surprise the attacker dug in the pocket of the frieze coat he was wearing, produced a folded paper and stuffed it into the coat front of the man before him. ‘With compliments,’ he said, then took a firm grip on his cudgel again.

The first swing of the club jolted the tall man out of his captors’ grip, across the pavement and into the side of the chaise. Billing gave another shriek as it rocked on its springs.

Jane threw open the door, reached out with both hands, grabbed the man’s arm and the collar of his coat and tugged. ‘Get in!’

Whether he heard her, or the momentum of his fall carried him in, she had no idea and she was far too worried about the gap-toothed snarl on the face of the cudgel-wielder to care. The man collapsed at her feet, the door swung in and then, as the chaise righted itself, came back on its hinges and hit the attacker in the face.

Jane took a grip on her parasol with one hand and dug frantically in her reticule with the other for Mama’s pocket pistol which was hopelessly tangled with her handkerchief. She was braced for the inevitable, when, with a blast on the horn, the Mail was on them. It swept past, forcing its way through the onlookers around the wagons. Their postilion seized his chance, whipped up his horses and the chaise, door still open, lurched into the wake of the stage and followed it through. As they passed the church the chaise tilted, the door slammed closed and they had left the Civet Cat and its ruffians behind.

Jane considered being sick, swallowed hard and let go of her weapons.

‘Miss Jane, tell the postilion to stop, this horrid creature is bleeding all over our skirts.’ Billing made as though to drop her own window to lean out.

‘Stop that,’ Jane said sharply. ‘Do you want those bully boys to catch up to us? Help me turn him over. Oh, do not be so foolish, Billing—have you never seen blood before? Put your feet on the seat then; at least it will give him more room on the floor.’

Billing huddled up in the far corner, managing in the process to kick the man who was prone at their feet. There was a groan. At least he was still alive.

Jane bent down and touched his shoulder and found good-quality broadcloth under her hand. ‘Can you turn over, sir?’

He grunted, began to lever himself up on his elbows in the restricted space and swore under his breath as the chaise hit a rut. ‘No.’

‘Very well, stay there. We will come to a turnpike gate soon, surely.’

It must have been about two miles before the chaise slowed, then stopped. ‘Help me, Billing. Billing.’

Somehow they hauled the man up on to the seat between them and it became clear that he was suffering from a knife wound in the shoulder, at the very least. There was blood, rather more than Jane felt comfortable with, and his left arm hung limp.

Jane stuffed her handkerchief and her fichu under his coat and pressed on the wounded area, ignoring the gasp of pain and the subsequent bad language. ‘Hold that.’ After a moment he obeyed, although his eyes were closed and his head lolled to the side.

She could sympathise with the gasp and she doubted if he was conscious enough of his surroundings to realise that he was swearing at two women. More of an immediate problem was Billing, who had recoiled further into the corner and was hectoring Jane on danger, impropriety, unladylike behaviour... ‘And what your sainted mother will say, I shudder to imagine. No respectable lady would consider for a moment—’

Jane stopped listening.

The postilion, having sorted out the toll, appeared to realise for the first time that he had an extra passenger. He handed the reins to the gatekeeper and came around to Jane’s window. ‘Here, what’s going on, miss? This vehicle was hired for two people.’

‘I know it was. I want you to stop at the next decent inn that serves stagecoaches and, I promise, you will be back to two passengers.’

He gave her a decidedly sceptical look. ‘It’ll be extra to pay at the end if there’s blood on the upholstery.’ But he remounted and sent the pair off at a canter and, as Billing finally ran out of breath, drew up at the Bell and Anchor.

‘Billing, please go inside and fetch a bowl of water,’ Jane said.

‘I’ll go in, that is for sure, but to try and get the blood off my skirts, Miss Jane! And I will send out some men to haul that vagabond out of our chaise,’ she added, scrambling down and marching into the inn. ‘I should be calling the constable, that’s what your mother would say...’ floated back to the chaise.

‘Quickly, unstrap her luggage,’ Jane told the postilion. ‘That wicker hamper and the small brown valise there.’ The stranger would have to look after himself for the moment because she needed to find her purse.

Just as Jane unrolled two banknotes Billing came marching out again without, of course, any water, but flanked by two anxious-looking waiters.

‘What’s about, Miss Jane? Those are my bags there.’

‘Billing, you are going home to Dorset. There is your luggage, here is more than enough money for the stage—you can pay for decent rooms and food on your way and a girl to accompany you. This seems a most respectable inn so I am sure they will advise you and let you hire one of the maids for the journey.’ She thrust the notes into the spluttering woman’s hands and closed the door. ‘Drive on!’

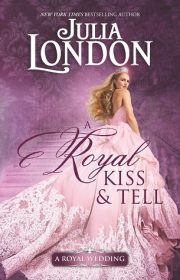

"A Royal Kiss and Tell" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Royal Kiss and Tell". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Royal Kiss and Tell" друзьям в соцсетях.