"You will study hard and obey the brothers," she said, suddenly stern with him. Then she lowered her voice. "If there is trouble, Oth and Dewi will come for you. Go with them without hesitation, Glynn. Promise me that, little brother."

"I promise," he answered her. He kissed her quickly on the lips and the forehead. "Go with God, Rhonwyn uerch Llywelyn, and return safely to us when you can." Then he turned and followed the brother who had come to escort him from the lord abbott's chambers.

Rhonwyn immediately burst into tears, flinging herself into Edward's arms and sobbing piteously.

"They have hardly been separated in all their lifetime," Edward explained to the abbott.

"It is good to see such devotion between a brother and sister," the abbott noted. Then he said to Rhonwyn, whose sobs were now sniffles, "We will take good care of your brother, my lady. I swear it."

"Th-thank you, m-my lord abbott," Rhonwyn managed to say.

They left the abbey and returned almost immediately to Haven where their party was ready to depart for the coast.

Katherine and her brother bid them adieu. "I shall pray every day for your safety and your success," she said softly. "Godspeed, cousins!" There were tears in her soft blue eyes, and Rhonwyn swallowed her jealousy when she thought Kate's gaze lingered a fraction of a second too long upon Edward.

"My husband and I thank you, dear Kate. We shall be grateful for your prayers," she returned.

Their train moved off down the castle hill onto the local road that would lead them to a wider and larger main road.

"What a woman she is," Rafe said softly. "The fates have played us both a nasty jest, little sister. You with your gentle ways would be a far better mate for Edward; and Rhonwyn with her fiery ways would find herself happier with me for a husband."

"Rafe!" Kate was shocked to hear him voice such sentiments. "Their union is the king's will," she said chidingly.

He laughed softly. "Do not scold me, Kate, for wanting what I shall never have. I firmly believe that they will both return one day."

The English army was to gather at Dover, and from there go on to Bordeaux. Their journey would be by both land and water. Barges took them from Haven down the Severn to Gloucester. They moved overland from there, skirting about the city of London and heading for their first destination at Dover. Arriving there in mid-May, they discovered that Prince Edward was not ready to go. Those already in Dover would leave England on one of the advance vessels for France and travel onward across the countryside for Aigues-Mortes on the Mediterranean Sea, meeting up with the French there. Prince Edward and his train would follow as quickly as possible.

"My wife was to be a part of the princess Eleanor's train," Edward told the port official in charge.

"She'll join the princess when Prince Edward reaches Aigues-Mortes" was the reply. "If she's going, she'll have to travel with you for now, my lord," the port official said. Then his manner softened. "There's another lady traveling on the ship I'm assigning to you, my lady. You'll share a tiny cabin and be company for each other. Her husband, too, is among the king's knights."

"My husband and I cannot be together?" Rhonwyn was distressed.

"The men will have to find places to sleep on the deck, my lady. You are going to war against the infidel, not on a honeymoon voyage," the port official said sharply.

"You will address me courteously, sir," Rhonwyn said, an equally sharp edge to her voice. "I am the prince of the Welsh's daughter, not some country squire's wife."

"Your pardon, my lady," the official quickly replied. "With the prince being delayed, I am at my wit's end trying to make everything come out correctly."

Rhonwyn nodded regally at him, and her husband managed to suppress his amusement.

The vessel aboard which they sailed from Dover was a large one. All their men-at-arms and the three knights, their horses, and their equipment was upon it, as was a smaller party from Oxford. They sailed in a season of good weather, but were at sea for ten days before reaching Bordeaux. The boredom that had enveloped them aboard ship evaporated as they now headed south overland for France's single Mediterranean port of Aigues-Mortes. As they traveled the road grew more and more crowded with noblemen, knights, and men-at-arms all bound for the same destination- and the crusade.

It was almost the end of June when they reached Aigues-Mortes. There they learned that Prince Edward had not left England yet. The English were not certain what they should do. The French king, frail, his eyes aglow with the fire of a zealot, came to speak with them all.

"We are assured," he said, "that your prince will join us, if not here, then in the Holy Land. He has sent word that those of you already here should follow me, and he will meet us as soon as he can. There are ships aplenty for you all. We are happy to have been chosen for so worthy a crusade on behalf of our dear lord Jesus Christ."

When King Louis had left them, the English began to talk among themselves. Some of them were angry, and others were reticent about following in the French king's wake without their own prince.

" ‘Tis typical of Edward Longshanks to leave us here at the mercy of the French," one knight grumbled. "He was so damned insistent that we be ready on time, and then 'tis he who is still in England."

"He will come," another man said. "I have heard it was difficult getting money out of the king for this venture. King Henry did not want his son to go, but the queen finally prevailed upon him, saying that enough good men were joining with the prince that it would be churlish if he did not come now, having already promised."

"And just where did you obtain your information?" the first knight asked, disbelieving.

"The messenger from our king who came to King Louis" was the reply. "A friendly mug or two of ale always loosens a good man's tongue, and this fellow had ridden hard to bring his message to the French from our Henry."

"What of the women with us?" came the question.

Now Edward de Beaulieu spoke up. "They must come as they had planned," he said. "We can hardly leave them here in France at the mercy of strangers. Besides, if the prince comes straight through from England, as I believe he will, he will not stop at Aigues-Mortes, and then our ladies would be stranded. We must see the French make accommodation for them."

"Aye."

"Aye."

"Aye" came the agreement of the men gathered together.

The French were approached. There were only six English noblewomen and their maidservants in the group. The French queen graciously invited them to travel to Carthage upon her vessel where they would be comfortable.

"After all," she reasoned to her husband, "these ladies were to travel in the train of my nephew's wife. We cannot simply cast them away. They are very brave, Louis, to have come with their husbands for Christ's sake. Until Edward and his wife arrive we must have a care for them."

The Eighth Crusade departed Aigues-Mortes on the first of July in the year twelve-seventy. The voyage to Carthage took them seventeen days and was uneventful but for their departure. Aigues-Mortes was France's only toehold on the Mediterranean, and it was a poor harbor. Separated from direct access to the sea by enormous sand dunes and girded about by large lagoons, the ships had to navigate through continuous and unceasing channels before reaching the open sea. It took a full day.

As they moved across the Mediterranean it grew increasingly warmer. Neither the English nor the French were used to such heat. The crusaders' encampment in Carthage was set up with its rows of tents, the great tent in the center of the camp belonging to the French king. There were cook tents for the soldiers and a hospital tent. Water was available but not in great supply, as some of the wells outside of the city of Carthage had obviously been deliberately poisoned. Sickness began to break out within the encampment despite the best efforts of the physicians to prevent it. Cesspits were dug for the epidemic of loose bowels that affected the men. They were quickly filled and covered even as new pits were being opened.

King Louis grew ill. He was not a young man, and the heat was taking its toll on him. Many around him were ill, including several of the English knights. When Edward de Beaulieu grew sick, Rhonwyn was at first overcome with fear, but then she rallied. The sickness, she suspected, came from the filth in the camp. She insisted on having their tent moved to the very edge of the encampment. The dysentery that affected him made his bowels run black and left him weak. Rhonwyn insisted the water her husband drank be boiled with three quinces, then strained through a clean cloth. Quinces were excellent for stopping dysentery, Rhonwyn knew. She then mashed the pulp of the stewed fruit with very sweet dates and fed it to him. The tent she kept scrupulously clean, emptying the night jar and cleaning it with vinegar and boiling water each time he used it. She recommended this manner of care to the French queen, but the king's physician laughed and said that Rhonwyn was old-fashioned. When the evil humors drained from the king, he would be well, and the crusade would continue as God had planned it.

Edward de Beaulieu had truly thought he was going to die, but then his wife's treatment began to work. His bowels stopped running, and his belly calmed. "Are you a witch?" he teased her.

" 'Tis but practical medicine I was taught at Mercy Abbey," she said with a smile, coming to sit on the edge of the camp bed where he now lay. Leaning down, she took a sea sponge from the basin of warm water at her feet and began to bathe him gently. The infirmarian at the abbey had always said that dirt was nasty and attracted evil humors no matter what the priests said about cleanliness being a vanity.

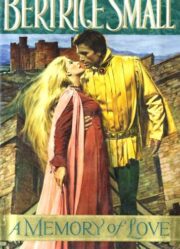

"A Memory of Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Memory of Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Memory of Love" друзьям в соцсетях.