"You are the damnedest woman," he complained to her. "You always were impossible, Gwyn, and I suspect that Rhonwyn is just like you." He laughed. "Very well, I will go myself and dicker for your saint's discarded fingernail. If necessary," he told her darkly, "I will steal it, but you shall have it, sister, and then you must keep your part of our bargain."

"Do not steal it, Llywelyn," she warned him sternly. "If you do, I cannot display it. I am not capricious in my desire for this relic. I would draw pilgrims to Mercy Abbey to ask the saint's blessing. Such a relic will prove profitable to us."

"It did not to St. Mary's in Hereford," he remarked.

"That is because they could claim no great miracles of it," the abbess replied with a small smile. "I am certain the saint's fingernail paring will be more content with us and work to the glory of God and Mercy Abbey, brother. In fact, I sense it in my heart."

He laughed roughly. "You are a devious woman, Gwynllian, and I thank God you were not born a man. Owain, Daffydd, and Rho-dri, our brothers, were easy opponents, but you, sister, would have been stronger than all three of them. I am not surprised you are abbess here."

She smiled archly at him. "Always remember, Llywelyn, that I am your equal. Our brothers were not."

"Are these all your demands?" he asked.

"I will also want a virile young ram, twenty ewe sheep, and a bag with a donation of ten gold coins. I will take either bezants, ducats, or florins, but their weight must be true. Make certain none of the coins has been clipped. These are all my requirements," she finished. Her dark eyes were dancing with pleasure at his look.

"You will beggar me, sister! The sheep I can obtain, but where the hell am I going to get so much gold for you? It is too much!"

"No negotiation, Llywelyn," she reminded him.

He swore a particularly vile oath, and the abbess laughed as he glared at her.

"1 haven't heard those words in many years, brother," she mocked him. "I had almost forgotten they existed."

"My daughter had better be able to compete with any princess alive when this is over and done with, sister," he warned her.

"She will," the abbess promised. Then she softened a bit. "It is already dark, brother. May I offer you and your men shelter for the night?"

"Nay," he snapped. "If I stay a moment longer with you I may be tempted to kill you, Gwynllian. There is a moon. We'll ride on. I said my farewell to Rhonwyn, and now I bid you adieu." He bowed briefly, and then stamped from the receiving chamber.

The abbess smiled softly as the door closed behind her brother. His brief visit had proved highly fortuitous for the abbey. He would do all she had asked him because he needed Rhonwyn for a treaty bride. Then Gwynllian grew more thoughtful. It was an enormous task she had been set, and she had to complete it successfully. Then suddenly she realized her brother had not taken Rhonwyn's foot pattern. Ringing for a nun, she sent the woman quickly after her brother so he could complete the task and get her niece decent shoes in Hereford.

She glided from her receiving room and across the abbey quadrangle to the guest house. There she found Sister Catrin seated with Rhonwyn. She dismissed the nun and joined the girl by the brazier.

"Well, he's gone. I've exacted a very high price from him for my help. You are going to have to work very hard, my child." She chuckled. "I could always get the better of your father and our other brothers. You know none of them, do you?"

"Nay, my lady abbess. At Cythraul, Morgan told me that the prince had overthrown and imprisoned his elder brother, Owain, and his younger brother, Daffydd. The youngest brother, Rhodri, is not an ambitious man, it was said. He sounds like my brother, Glynn."

"If Wales is to be united, there can be but one ruler," the abbess answered her niece. "Your father finds it hard bowing his knee to any, even almighty God. He only knelt to the English because by doing so he obtained what he wanted."

"There is no shame in that," Rhonwyn considered.

The abbess chuckled. "You are a practical lass, I see. That is to the good. I told your father I would do nothing to help you until he fulfilled his word to me, but that is not true, although he will believe it, having never caught me in a lie. You have so much to learn that we must begin tomorrow if we are to have any chance of passing you off as a noblewoman in six months' time. Llywelyn will do what he must for me. Now tell me, child, you have never had any women companions?"

"Not since Mam died," Rhonwyn answered her aunt. She looked about the little hall of the guest house. "Am I to stay here alone, my lady abbess? I have never been alone before."

Gwynllian shook her head. "I have two young postulants with us right now who are near your age. They will come and make their beds with you, Rhonwyn, so you will not be by yourself. They must, of course, attend to their own duties during the day, but you will be busy with your studies. They will share your chamber; you will eat together in the refectory with the community; and you may take walks in the gardens. We do not have a school like some other convents, so you will he unique as a student, my child."

"What of my horse?" Rhonwyn asked.

"It is salely in the stables. Do well at your studies, and I will permit you to rule it," the abbess said.

"But Hardd needs his exercise, my lady abbess!" Rhonwyn protested.

"You may walk him daily belore your lessons, my child, but there will be no riding unless you progress in your duties," the abbess said. Then she held up her hand to prevent the further protest she saw on Rhonwyn's lips. "One of your first lessons is obedience, which means doing what you are told by your superiors. You obeyed Morgan ap Owen because he was your captain or superior. You must obey me for the same reason, my child. Obedience and good manners can cover a multitude of other sins, Rhonwyn. You have been raised in a community of rough men. I know they had good hearts, for I can see you miss them, and you would not had they been unkind; but soldiers are not the best example for a young girl to follow. Come with me now, and we will go to the refectory to have something to eat. Tonight I will excuse you and the companions I have chosen for you from Compline, but beginning tomorrow you will attend mass daily." Then she patted Rhonwyn's hand. "You know nothing of God and our dear Lord Jesus, do you, my child? This is all very confusing, I can see. Do not be afraid of your innocence and your ignorance, Rhonwyn. You will quickly learn, I promise you. You are an intelligent girl, and your mind, I already see, is facile."

For the first time in her life Rhonwyn found herself uncertain and retiring. She followed her aunt from the guest house to the refectory, which she quickly learned was a place where the nuns dined. The women who lived in this abbey were called nuns. They were also called Sister, except her aunt who was Reverend Mother or my lady abbess. And the nuns were ranked according to the position they held within the community.

Her companions, Elen and Arlais, were called postulants and were the lowest on the abbey's social scale, being considered candidates for the religious order. The novices, and there were five of them currently, had completed their year's training as postulants and now were spending the next two years preparing to take their final vows. The vows were those of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Rhonwyn knew what poverty and obedience meant. Chastity, she learned, was a promise to remain pure, which meant no going beneath a hedge with a man or doing what her father used to do with her mother.

The nuns devoted their lives to God, the supreme being. She hadn't heard enough of God at Cythraul to make any sense of him. Now her new companions, Elen and Arlais, spent their evenings teaching Rhonwyn as they would have taught their children had they wed instead of entering the abbey. They found Rhonwyn rather fascinating, never having known anyone like her before, but they also treated her with respect, for she was the abbess's niece and the prince's daughter. Elen and Arlais were the daughters of freedmen who farmed their own land. The three girls got on rather well despite their dissimilar backgrounds.

Rhonwyn went with her companions to the early church services of the day, Prime, at six o'clock in the morning, and Tierce, the high mass, at nine o'clock in the morning. She attended Vespers before nightfall, but was excused from the other five canonical hours. After Prime she broke her fast in the refectory with oat porridge in a small bread trencher and apple cider. She then sat with Sister Mair until Tierce, practicing how to write both letters and numbers. Sister Mair did the lettering on the illuminations the abbey sold to noble households.

After Tierce, Rhonwyn studied with her aunt, learning Latin and the Norman tongue. To the abbess's delight her niece had a facility for languages other than the Welsh tongue and learned far more quickly than she had hoped. Within a month Rhonwyn was reciting the Latin prayers in the church services she attended as if she had been doing it all her life. And she was beginning to read as well. Her ability with the Norman tongue was equally swift, and Rhonwyn was soon conversing in that language on a daily basis with her aunt both in and out of the classroom.

Gwynllian uerch Gryffydd gave thanks before the altar of the church daily for her nieces progress. It was truly miraculous. Alter the midday meal Rhonwyn joined Sister Una in the kitchens so she might see bow meals were planned and prepared. Here her progress was not as quick, and Sister Una complained to the abbess that her niece could burn water. The infirmarian, Sister Dicra, was kinder, for her new pupil seemed to have a knack for healing and concocting the potions, salves, lotions, syrups, and teas needed to cure a cough or make a wound heal easier.

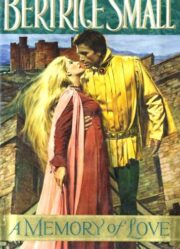

"A Memory of Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Memory of Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Memory of Love" друзьям в соцсетях.